In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

It’s easy to forget that visions of a unified Europe existed long before the creation of the EU. From the Christian visions of Charlemagne to the radical visions of Napoleon Bonaparte, how have Europe’s blueprints differed throughout history, and what can they teach us about the present?

Before it solidified in a political union, the idea of a united Europe had many different blueprints. Christian, imperial, liberal, conservative, and socialist visions all vied for supremacy, and while the liberal-technocratic model won out in the end, in the form of the EU, those earlier strands still run through contemporary visions of Europe’s future.

It’s May 9th, 2025, and I’m scrolling Instagram on my way to work. A reel comes up from an account named saveeurope, featuring a montage of Greco-Roman sculptures, photos of white families, and renaissance architecture accompanied by bass-boosted Eurodance music. The tune is L’Amour Toujours, the French named, Italian-produced, and English-sung 90s party-anthem which in 2024 was co-opted by German nationalists who recorded themselves chanting Ausländer Raus! (Foreigners Out!) along to the song’s catchy melody.

Gigi D’Agostino, the song’s creator, was understandably bewildered to learn his legendary tune was being maliciously blasted at immigrants from Bluetooth speakers around Germany. “The song is about a wonderful, big and intense feeling. It is love,” Gigi inisited to Der Spiegel magazine. Outside my office, the yellow public transit buses are decorated with the EU-flag. Turns out it’s Europe Day.

‘Europe’ is an idea with many meanings and with an equally contested past and future. The juxtaposition of marble sculptures and eurodance may be a novel combination, but the nativist vision of a Europe under siege from outside invaders – with refuge found in ancient symbols of ‘Europeanness’ – isn’t. And it’s just one of many competing narratives prevalent today – along with liberal, conservative and socialist ones – which all have deep historical roots. These diverging ideas have taken different forms throughout history, but the red thread connecting them is a common striving towards achieving internal peace amid periods of crisis.

Prior to the Enlightenment, ‘Europe’ was almost exclusively conceived of as a geographical area. The Greek goddess Europa – whose name some scholars trace to Semitic and Phoenician terms for ‘west’ and ‘sunset’ – symbolically marked the continent’s Eastern boundary. In Greek and Roman antiquity, Europe referred to lands west of the Bosphorus Strait in what is now Türkiye. Over time, this boundary was expanded to exclude that which lay south of the Mediterranean Sea, and, later, east of the Ural Mountains.

Why have these natural barriers persisted in our definition of Europe? The answer is found in the layered histories of conflict playing out along their edges.

The Bosphorus Strait has been a site of struggle between Christianity and Islam, significant both during the crusades from the 11th to 13th century and during Ottoman expansion westward, as well as the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Similarly, the Strait of Gibraltar, separating the Iberian Peninsula from North Africa, stood as the final threshold of the Christian reconquest of the peninsula which ended in 1492. Through such events, shared contours for the first vision of Europe as a political unit began to emerge: a fortress united through Christendom.

Taking a retrospective approach to the European idea, one of the first expressions of a European identity rooted in Christianity appears in the mythologising of Charlemagne, King of the Franks and Emperor of the Carolingian Empire (718- 814AD). Though calling Charlemagne ‘European’ would be a revisionist stretch, his post-Roman unification of much of Western Europe made him an attractive archetype in the imagination of later pan-European political projects. A millennium onwards, Napoleon Bonaparte would cast himself as Charlemagne’s heir, justifying his own attempt to remodel Europe by force of arms.

The transition from medieval to early modern period saw a growing sense of collective European Christendom – fostered both from within and pressures from beyond the continent. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Pope Pius II called on Europeans to unite, quell their internal conflicts and mount a joint military campaign against the Muslim Ottomans on Europe’s Eastern frontier.

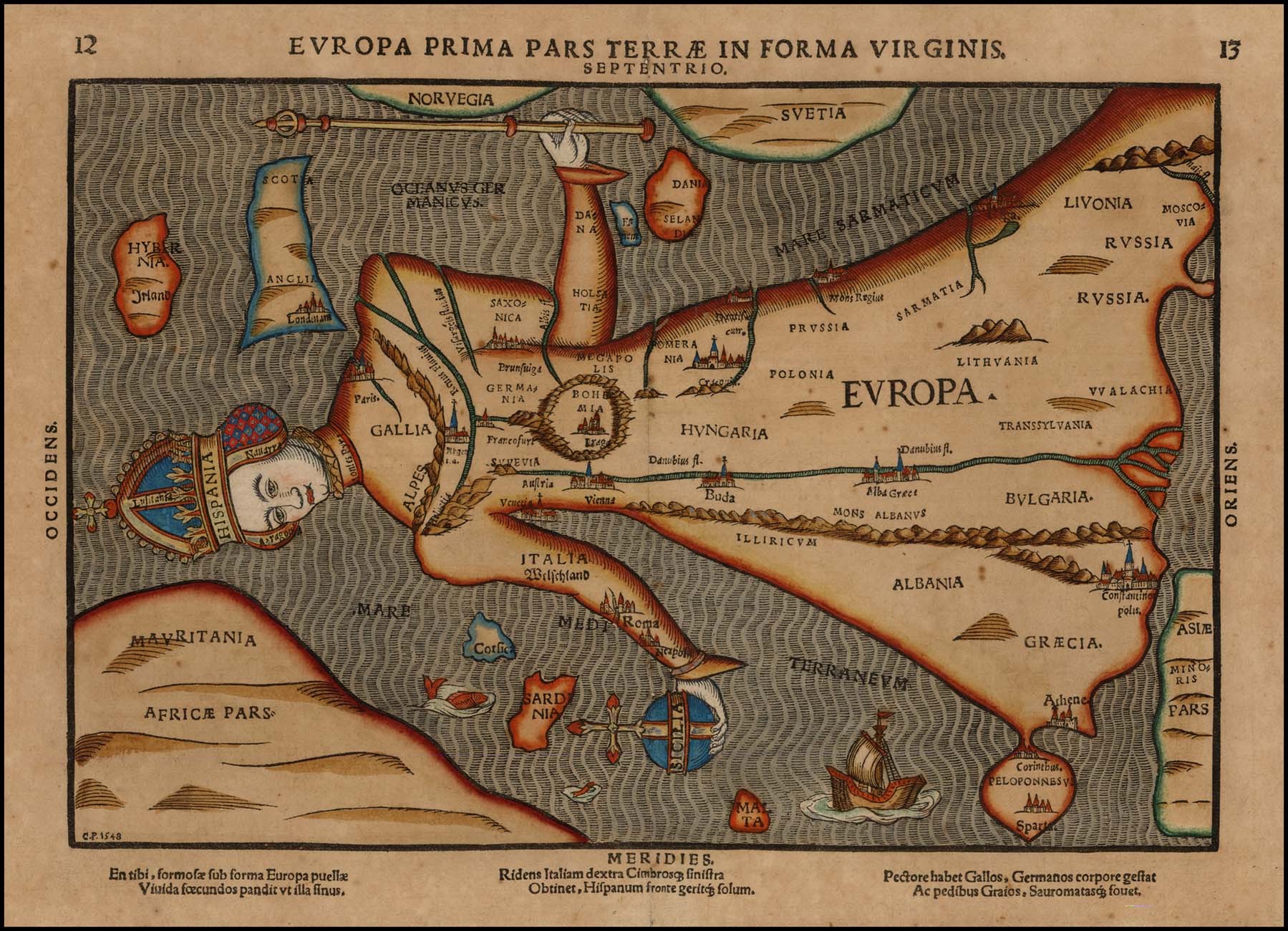

Internally, a rising production of cultural artefacts reflected this mood of a shared European identity. Sixteenth century literature – from Cervantes to Shakespeare – spelled out a Europe united through its Eastern and Southern exclusion. As historian Mats Arlén describes, by the turn of the seventeenth century, Europe “began being used as a noun and an adjective”, a concept encountered in books, political circles, and pamphlets satirising the threat of invasion from the Orient or the Steppes. Maps from the sixteenth century, for example, personify Europe as a regal Christian queen embellished with religious ornaments, stretching from the Atlantic to the Russian steppes.

The loftiest pan-European political vision prior to the Enlightenment may be found in the memoirs of the Duke of Sully, published in 1641. Serving under King Henri IV of France, Sully imagined a reorganised Christian Europe featuring everything from supranational institutions to a pan-European senate. His “Grand Design” aimed to maintain internal peace among Christian states in Europe as well as coordinate a response to external threats, notably from the Turks.

Though political in nature, these ambitions did not seek to establish a distinctly European consciousness independent from Christendom. As such, by the 17th century, this premature shared foundation was already being fractured by the Protestant Reformation. Nor were these early European schemes anything we’d consider close to federalist or politically homogenising in scope. To claim that people in 17th century Europe identified themselves as European – even in a geographical sense – would be an anachronism. People’s allegiances lay with their local communities. Though some entertained soft visions of uniting Christian kingdoms, these were sparse and tenuously linked to the idea of Europe itself.

This changed during the Enlightenment. Scientific revolutions, political reorganisation, and a renewed emphasis on philosophy in the 18th century gave rise to a range of pan-European ideas which differed in ideology yet converged along shared lines of European modernity’s signature traits, such as progress, teleology, and manifest destiny.

The concept of a continent united through striving towards peace reappeared, now in a secular form. In the late 18th century, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant argued that a “perpetual peace” in Europe could only be achieved through a federalised system of free, republican states. For Kant, this peace was not only a normative goal, but a teleological certainty – an inevitable result of humanity’s rational moral progress.

Kant’s contemporary, the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, similarly drew from his liberal philosophy of statecraft in imagining a united Europe. However, while Kant’s idea was universalising in scope, Rousseau’s vision of Europe consisted of contracting the sizes of states and assembling a European confederation, similar to the Helvetic League or Holy Roman Empire. Rather than grounding a European polity in Christianity, thinkers like Rousseau and Kant framed European unity as a natural progression of the continent’s rational statecraft.

This vision coincided with a fascination with the recently established United States of America. For many, the young republic represented an ‘Enlightened’ form of democratic governance tapping into the philosophical zeitgeist of the age. Marquis de Lafayette, a central figure in both the American and French revolutions, argued Europe should emulate federalist statecraft from across the pond.

As the 19th century unfolded, the European idea began to consolidate along distinct ideological lines – liberal, conservative, socialist – that are recognisable to us today. Their shared foundational moment, whether in admiration or criticism, came with the 1815 Congress of Vienna: a series of diplomatic meetings held in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars to, yet again, ensure peace on the continent. Here, the British historian Perry Anderson argues that the meetings birthed a decidedly conservative strand of the European idea founded on balancing out traditional powers and where future peace would be maintained through continued summits among the continent’s elite representatives.

Meanwhile, on the small Atlantic Island of Saint Helena, an opposite, more radical imaginary was being penned down by Napoleon Bonaparte that same year. The exiled Emperor claimed that his ambition had been to introduce a European association for its overall prosperity: “We need a European law code, a European supreme court, a single currency, the same weights and measures, the same laws… I must make all the peoples of Europe into a single people, and Paris, the capital of the world.”

Though distancing themselves from the Napoleon’s military expansionism, several European thinkers in the mid to late 19th century embraced a socialist, revolutionary, and often Francophone strand of the European idea. In what might seem counterintuitive to how European nationalism is framed today, these leftist visions of a United States of Europe were almost always rooted in strong, sovereign nation states. Nationalism, at the time, was closely aligned with a radically democratic conception of the people’s will. Only through the creation, cooperation and eventual merging of robust democratic republics, would a “European brotherhood” take hold.

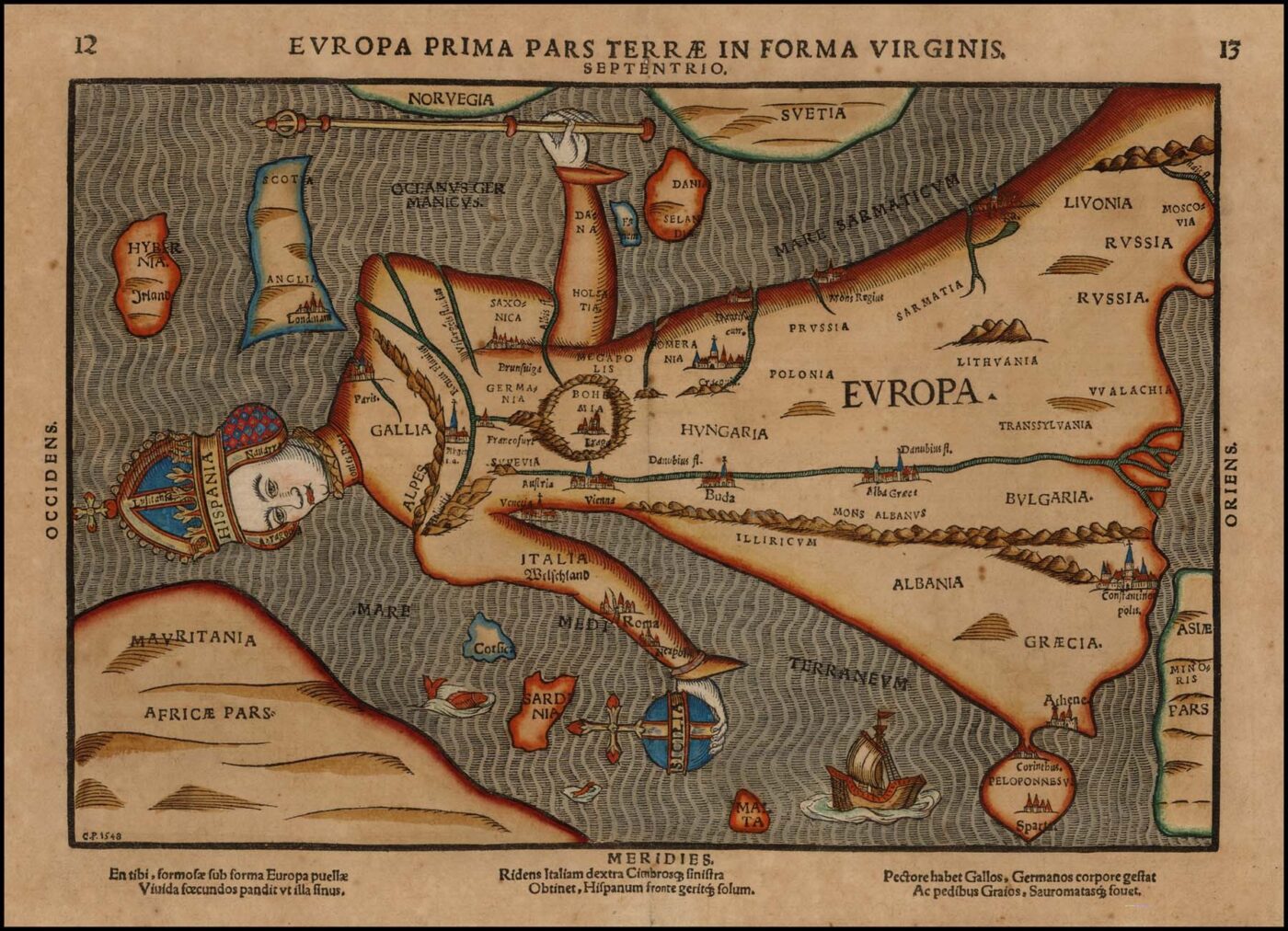

One of the most influential proponents of this idea was the French writer Victor Hugo. The author of Les Misérables held an inaugural speech during the 1849 Paris Peace Congress, calling for the abolition of Europe’s internal borders and envisioning the day when we would see “the United States of America and the United States of Europe stretching out their hands across the sea”. Discourse relating to European integration peaked in France after the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), where the recently established German Reich headed under Otto von Bismarck shattered the delicate power balance in Europe maintained since the Congress of Vienna. Further calls for European unity by Hugo and other French leftists were marked by this turning, with Hugo arguing in 1870 that “[a] United States of Europe speaking German would mean a delay of three hundred years. A delay, that is to say, a step backwards.”

Alongside this left-republican vision emerged a contrasting liberal, market-oriented one, shaped by events across the Atlantic. The admiration for America crystalised into calls for a European equivalent for economic reasons. Indeed, this vision is where the European Union’s etymology traces back to. An example is the German businessman and popular advocate of European free trade August Schmidt-Phiseldeck, who in 1821 proposed the creation of a European federation and customs union titled the European Union while in Copenhagen. In preemptively globalising fashion, Schmidt-Phiseldeck described such a union as a “role model for the rest of the Earth.”

Though ideologically diverse, these liberal, conservative, and socialist pleas for the unification of Europe were chiefly grounded in the same practical concerns: the desire to prevent internal wars and defend against an external other. Yet, common ground was also forming outside of the legal and political realm. By the mid-19th century, the idea of civilization was on the lips of European intellectuals, and the lauding of a distinctly European civilization was beginning to take hold.

These ideas were greatly shaped by Enlightenment-era scientific thinking and a growing trend towards cultural Orientalism, both of which strengthened a sense of European exceptionalism. The German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Frederich Hegel (1770-1831), for instance, proposed that although world history began in Asia, it would conclude in Europe. Hegel assessed that Europe held the telos and final destination of reason itself. Here was where the free wills of individuals would find their fullest expression.

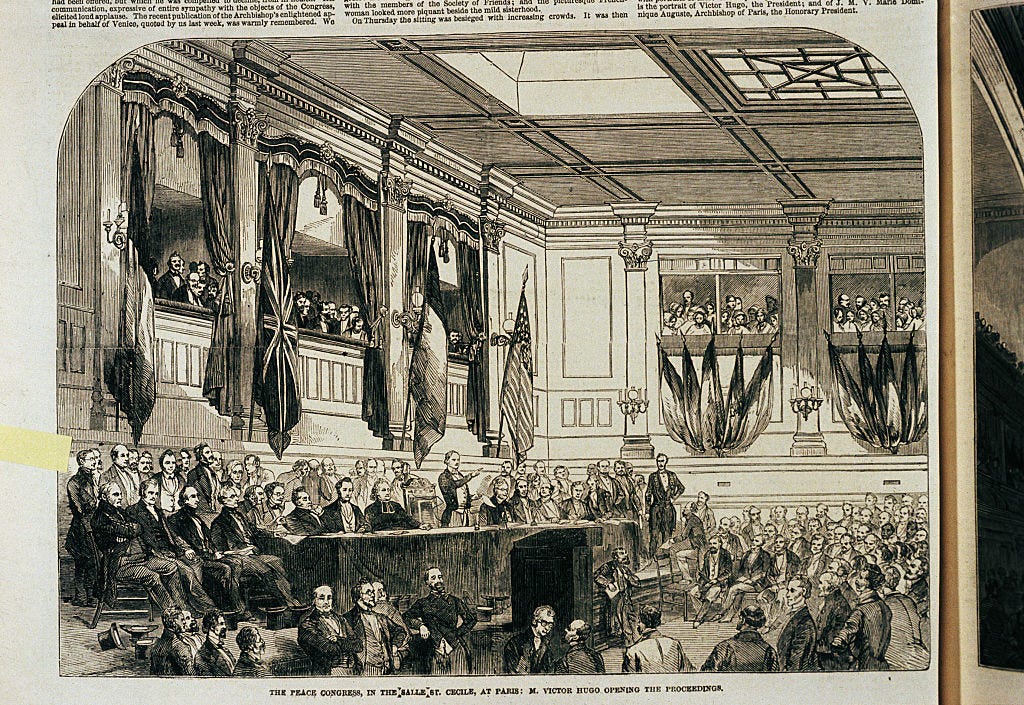

By the late 19th century, the concept of European civilization had become widespread. While many celebrated Europe’s civilizational supremacy (and in a colonial context, its mission), others argued that European vanity was disguising a deeply rooted sickness. Frederich Nietzsche (1844-1900) perceived a Europe marching blindfolded towards a crisis of values. In his text European Nihilism, the German philosopher argued that if Europe had an identifiable civilization, then it was one marked by moral hypocrisy. Europe was emblematic of Nieztsche’s last man: a spiritually ugly, resentful civilization masking its self-contempt with performative illusions of grandeur.

Nietzsche traced this decay to what he saw as Europe’s overreliance on Enlightenment ideals, such as democracy, scientific objectivity, and humanitarianism, which he claimed had severed the continent from the heroic values of Greco- Roman antiquity. Europe, Nietzsche wrote, was best expressed through its great men: Napoleon, Goethe, Wagner, and Charlemagne. What the continent needed was a rebirth.

Although the use – and abuse – of Nietzsche’s thought remains a contentious topic, what is clear is that his call for civilizational rebirth was premature, first becoming politically relevant in 1914, fourteen years after his death. For many, the First World War was evidence that Europe was not progressing towards reason, peace, and civilizational supremacy, but going in the opposite direction.

While the European Union’s foundations are usually traced to the barbarism of the Second World War – the blood-soaked beaches of Normandy, the gas chambers of Auschwitz, and the ruins of Dresden – serious calls from a wide range of politicians, writers, and artists for a pan-European project had already begun after 1918.

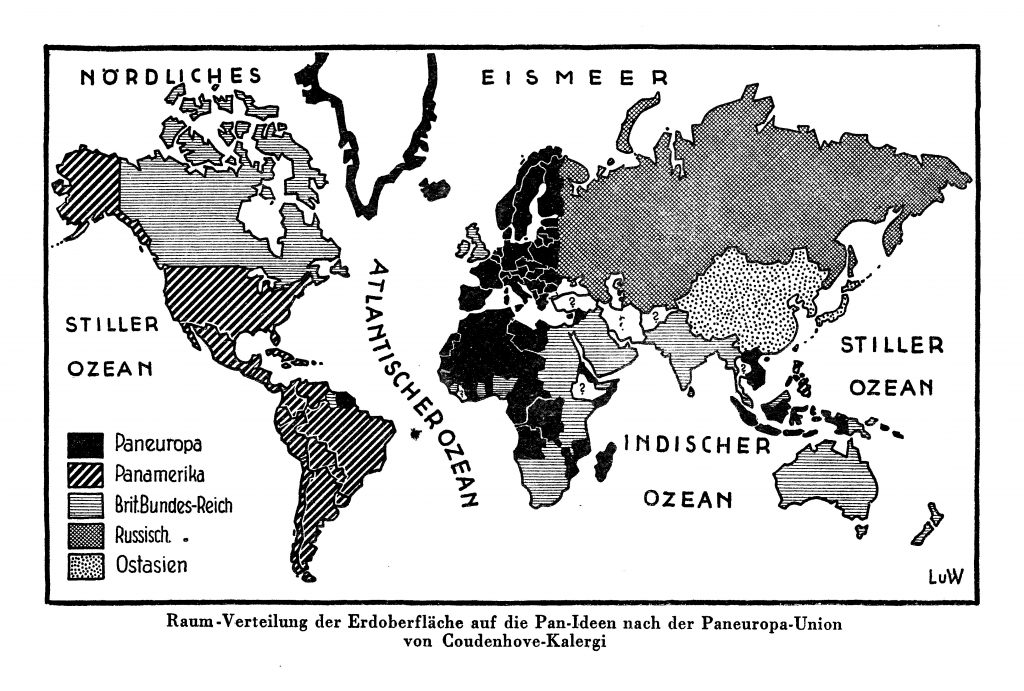

Its clearest expression was in the founding of the International Paneuropean Union in 1923 by Austro-Japanese political thinker Richard von Coudenhove- Kalergi. The Paneuropean Union called for the continent’s peoples to unite in peace, guided by shared humanist and Christian values. The continent-wide shellshock following the First World War made the 1920s uniquely fertile for multilateral movements across the political spectrum. The Paneuropean Union attracted a diverse range of supporters, including Thomas Mann, Winston Churchill, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, and later, even Charles de Gaulle.

But pan-European ideals also found resonance within fascist movements. The Nazi politician Gregor Strasser expressed admiration for Coudenhove-Kalergi’s vision of European unity, though reframed through a nationalist lens. He advocated for a shared European Colonial Company that would save the continent’s faltering and competing empires by pooling their resources together.

Across the English Channel, Sir Oswald Mosley, who led the British Union of Fascists until its suppression in 1940, had an explicit Europe a Nation policy: a plan to integrate Europe into a single political entity. During the Second World War, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Nazi Germany’s Foreign Minister, proposed a European Confederation comprising of the sovereign states of Nazi-occupied Europe. Although Hitler rejected the idea as incompatible with the vision of a thousand-year German Reich, the proposal found ideological sympathy in Vichy France and fascist Italy.

The leftist vision of European unity, so prominent in the 19th century, faded from political prominence in the 20th – largely due to its entanglement with communism and the East–West ideological divide. In its place, the European idea as we now know it was forged in the 1950s in a fusion of liberal and technocratic ideals shaped by the failures of the interwar period and the ruins of the Second World War. But a genealogy of Europe reveals that this model – the one institutionalised in Brussels and codified in treaties – is only one strand among many. Throughout modern history, the idea of Europe has taken revolutionary, imperial, conservative, and even fascist forms. And yet, across these competing visions, two themes persist: the struggle for peace, and the catalyst of crisis.

This article was first published in Issue 14: European Futures