In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Cooking Up the Future

On how the Italian artist and ideologue Filippo Marinetti attempted to remould his countrymen

into the model citizens of a new fascist state – starting with their bellies.

/

On the surface, former Danish government minister Dan Jørgensen and the Italian artist Filippo Marinetti may not appear to have much in common. For readers who are unfamiliar with them, Marinetti was the founder of the futurist art movement in Italy in the early 20th century. He later became an ideological companion to Mussolini, and he co-authored the fascist manifesto prior to the party taking power in Rome in 1922. Dan Jørgensen, a world historical lightweight by comparison, was the Danish Minister for Food, Agriculture and Fisheries from 2013 to 2015.

Their many differences aside, they have one notable thing in common: both of them based part of their political projects on the idea that if you want to change a culture, you should change how people eat.

In 2014, Dan Jørgensen launched a nationwide poll to decide the national dish of Denmark (there hadn’t previously been one). It was his hope that the vote would spur a discussion about the importance of sourcing ingredients locally, while helping to ‘bring the nation together through food’, as the minister put it.

Indeed, the result of the poll, in which the choice fell on the homely dish Stegt flæsk med persillesovs, did spur debate, notably concerning the state’s role in manufacturing community through the selection and exaltation of symbols of nationhood. Some questioned whether the dish, consisting of fried pork belly and boiled potatoes served with a rich parsley sauce, was a good fit for an increasingly diverse country, given that neither Muslims, Jews, vegetarians, or vegans (who together make up a sizeable and growing portion of the Danish population) eat pork. More broadly, some doubted whether any single dish could ever represent the food habits of 5.5 million people, which would mean the minister’s initiative was futile by default.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberAlthough the vote garnered significant national attention, Dan Jørgensen arguably failed to change the culture through food – at least in the direction he had envisioned. So what does this have to do with Marinetti?

After having entangled himself in the fascist project, the Italian artist became engaged with Mussolini’s efforts to remould the Italian nation into one that would be suitable to fight the industrialised wars of the future. One key to success, Marinetti believed, would be to revolutionise how Italians ate.

Through a series of publications from the early 1930s, Marinetti declared war on gnocchi, macaroni, and spaghetti. These nationally beloved dishes, he thought, were to blame for the pessimism and lack of virility that he saw in the Italians. “People think, dress and act in accordance with what they drink and eat,” Marinetti wrote, and so stimulating a change in their diet would bring their behaviour more into line with the needs of the state. Substituting pasta with Italian-grown rice, for instance, would serve the double purpose of weaning the Italian people off their flour-heavy diet and liberating the country from imports of foreign grain, thus supporting the regime’s ambition to build an economically self-sufficient nation populated by healthy citizens in fighting shape. Yes, Marinetti may have been a warmongering fascist ideologue, but he was also a vocal proponent of locally sourced, low-carb meals!

Like Dan Jørgensen, Marinetti wanted to bring the nation together through food, although with more sinister aims than the Social Democrat minister can be accused of. His most ambitious effort in this regard was the publication of the Futurist Cookbook from 1932, which reads like an oddball revolutionary manifesto: part provocation, part ideological text, and part joke. Yet for all its novelty, the cookbook fitted well into the ongoing futurist project of undermining anything traditional and reshaping society to be in tune with a new age of technology. In the futurist conception, humans would need to change their behaviour to fit the dictates of technology, and the future would be conquered by men and their machines. Fittingly for this ideological project, in which food and diet would also play their part, Marinetti wrote: “This Futurist cooking of ours, tuned to high speeds like the motor of a hydroplane, will seem to some trembling traditionalists both mad and dangerous: but its ultimate aim is to create a harmony between man’s palate and his life today and tomorrow.”

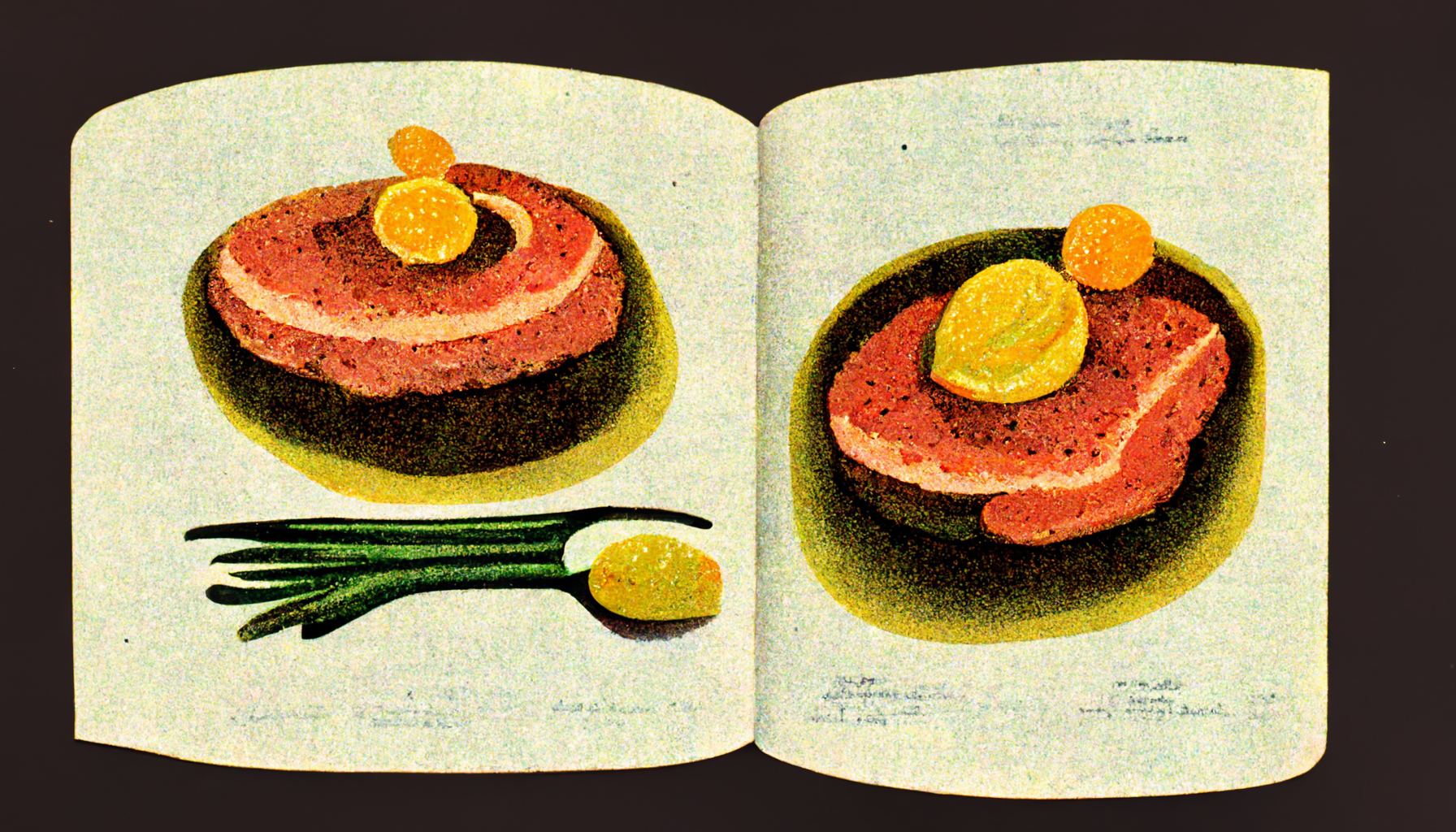

Inside the book are eleven requirements for a futurist meal which include “absolute originality”, the use of music between meals for the purpose of “re-establishing gustatory virginity”, and the abolition of cutlery, as knives and forks interfered with the “pre-labial tactile pleasure” of eating with your hands.

The recipes include plenty of unorthodox ingredients that don’t traditionally go together. They make creative use of raw meat and eggs, with a heavy emphasis on using aromas and perfumes to enhance the dining experience. Most of them read like practical jokes and seem quite disgusting, although (full disclosure) since I have not tried any of the dishes, I can’t comment on their culinary value. But of course, that is not really the point. Taste is but one of our senses, and Marinetti wanted eating to be a full-body experience – rousing and provocative, rather than familiar and comforting. On the list of recipes, we find Intuitive Antipasto – a hollowed out orange containing salami, butter, pickled mushrooms, anchovies, and green peppers. Inside the peppers themselves, like futurist fortune cookies, small cards are inserted with inspiring catchphrases printed on them. Or how about some Zoological Soup, jam-filled pastries in animal shapes (made from eggs and, of course, Italian rice flour) served in pink broth and scented with Eau de Cologne? For the more adventurous diners, there is also Aerofood – not merely a dish but a fully immersive eating experience meant to simulate taking in your meal in the cockpit of a fighter plane: With the right hand, black olives, fennel hearts and kumquats are eaten off a plate, while the left hand strokes a rectangle of sandpaper, silk, and velvet. Meanwhile, waiters spray the diners’ necks with perfume, and the kitchen blasts out recordings of an aeroplane motor and symphonies by Bach at full volume. Eating has never made you feel more alive.

Did Marinetti succeed where Dan Jørgensen failed? Not in the ways that mattered to him. Today, the average Italian consumes 23.5 kg of pasta in a year – a world record. And the fascists and futurists eventually lost the world war they had been cheering on. Marinetti didn’t live to see the end, having died from cardiac arrest in 1944. Reading the Futurist Cookbook in an era when chefs are hailed as rock stars, you could say that he did anticipate the food-as-art revolution that would eventually engulf the globe, although it didn’t pan out quite as he had imagined.