In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Four scenarios for the next decade

Illustration: Lovisa Volmarsson

Many of us struggle with uncertainty, perhaps because our brains are poorly equipped to handle it. We are wired to look for patterns, establish coping mechanisms, and utilise mental shortcuts to conserve energy. Uncertainty provides us with few patterns on which to base our decision-making – dealing with it can be mentally exhausting.

Yet uncertainty is inherent to the future, and any attempt at anticipating it will need to accept rather than ignore this fact. As a form of futures inquiry, foresight does not avoid uncertainty but acknowledges and indeed embraces it. Foresight enables us to sort through the noise of signals, determine which key drivers of change to monitor, and explore how their interactions give rise to novel outcomes not previously anticipated.

Scenario building is a foresight method developed for exactly the kind of turbulent times we live in today. It allows us to explore multiple plausible outcomes in a structured manner by focusing our attention on a finite number of factors. It makes the uncertainty inherent to the future less overwhelming and helps foster a culture of preparedness rather than prediction.

Europe’s future is contested and full of uncertainty. Applying a scenario approach to discussing it, which we have done on the following pages, can sharpen our sense of what’s at stake and stress test our ability to face a range of different outcomes – both the ones we find favourable and the ones we’d prefer not to think about.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

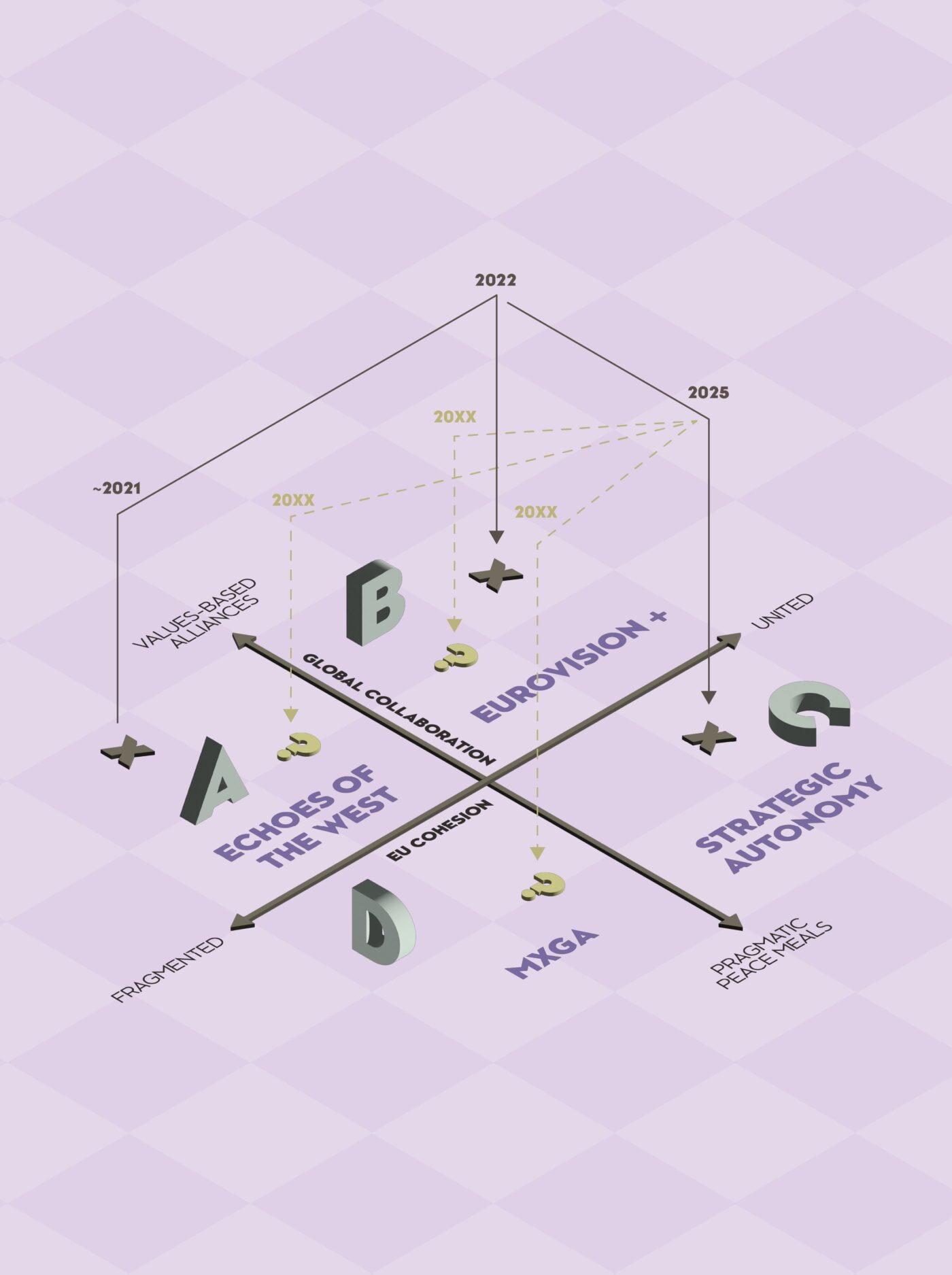

become a futures memberWe focus on two crucial themes: European cohesion and global collaboration. These themes make up our two scenario axes, which in combination provide us with four distinct scenarios encompassing both Europe’s internal dynamics – fragmentation or unification – and external relations – a world order anchored in values-based alliances or a more pragmatic, transactional system of global relations. We approach Europe primarily, though not exclusively, through the lens of the EU.

Although scenarios are not predictions, they must be plausible and believable to be effective tools for thinking, planning, and decision-making. If a scenario feels too far-fetched, it may be dismissed outright regardless of any useful insights it might contain. Plausible scenarios help anticipate realistic challenges and opportunities, prompting thoughtful policies or strategies. Implausible ones may lead to misguided or even dangerous actions if taken seriously.

Any doubt as to whether the four scenarios presented here meet the criterion of plausibility can hopefully be put to rest through a brief historical recap showing how quickly things have changed in the recent past alone.

Take Scenario B (circa 2022), characterised by a high degree of global collaboration and a united Europe. This was a time when European leaders almost universally put their faith in a strong NATO and had no reason to doubt the vitality and necessity of the transatlantic relationship. Internally, European unity was galvanised in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Before that, we were in Scenario A (2021 and prior), with strong transatlantic relations and global institutions, but also a more fragmented Europe characterised by ‘northern fatigue’ with ‘southern issues’, Brexit (and the looming risk of other possible exits), a geographically uneven aftermath of the financial crisis, and finally the Covid-19 pandemic. Today, we find ourselves in Scenario C, with a somewhat cohesive Europe enjoying high internal support (both political and public) but struggling to navigate a greatly disrupted international landscape.

When considering how these same scenarios map onto the future, several questions come to mind: are we one right-wing election win in a major European country away from ending up in D? Will the US 2026 midterms pull us back toward B? Will Europe commit itself to internal strengthening while seeking new partners in the world, keeping us in C?

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereWe will explore mechanisms that could move us between the different scenarios and what developments that could support these shifts on the following pages, along with the very different implications they may have for people, businesses, and policy makers.

And while we do that, it is important to remember that our initial emotional response to change, or to one scenario or another, may very well be anchored in our cognitive biases rather than actual potential outcomes. The reality is that every scenario has winners, losers, risks, and opportunities. Disengaging our emotions through foresight allows us to truly engage with plausible outcomes, test our strategies, discuss ‘what needs to be true?’ for something to happen and thereby arrive in the future better prepared.

In the end, some will get the future they ‘want’ and thus thrive, while others will find themselves in a less favourable future – but will have hopefully come prepared. Others still will be hit by an unfavourable outcome and taken by surprise. The latter are likely to struggle, or even wither and disappear. Foresight is a good antidote to falling victim of future circumstance.

We begin in Scenario A, with a more fragmented Europe in a world of strengthened global collaboration and a resurgence of the transatlantic alliance.

What could take us there? For one, a strengthening of transatlantic ties would require the emergence of a ‘saner’ United States that manages to halt its slide toward autocracy, assumes a less belligerent posture vis-à-vis Europe, and recommits to shared values and ideology.

In this scenario, the loosening of outside pressures would see renewed fragmentation and division within Europe. 2025 marked the highest ever level of public support for the EU among citizens ever recorded (74%, as measured by Eurobarometer), but this unity is in large part thanks to a sense of being ‘under siege’ from threats in the form of a belligerent US and a Russia at war on Europe’s frontier. A peace agreement in Ukraine and a change of direction in the US might have an adverse effect on European cohesion.

We can detect signals today that point to this possible future. Migration continues to be a point of division within Europe, with nine member states – including Italy, Denmark, Austria, and Poland – having recently called for a reinterpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights to facilitate the deportation of irregular migrants. Energy is another source of disagreement, with Hungary opposing EU plans to phase out Russian gas and LNG being a recent example. The green agenda also breeds contention, with France and Germany having recently called for the repeal of the EU supply chain law, which obliges companies to ensure human rights and environmental standards throughout their global supply chains.

Should we move toward this scenario, what would Europe look like for people, policymakers, and businesses?

For citizens, digital privacy and other user-centric regulations might suffer, being forced by Europe’s bigger economies to give to boost competitiveness. Democratic engagement at the state level might increase even as they decrease on EU level. Populist narratives could thrive in regions feeling ‘left behind’.

On a policy level, Scenario A could put us on track for the end of Schengen, or at least toward largely weakened mobility rights and opportunities. We may also see a weakening of regulations around state aid and competition. EU institutions could become increasingly paralysed, adding to incentive for reform that relinquishes control in favour of national sovereignty. Imperatives for strengthening Europe’s security would likely remain low as long as the Western alliance stands (“the US will ensure that there is stability”).

In a Europe less united and less committed to self-strengthening, the EU’s ability to regulate big tech could become effectively non-existent. Member states may also begin more experimentation with migration and economic policy – becoming isolated ‘policy labs’ – as the EU becomes increasingly unable to regulate or enforce authority in these areas. Europe could ultimately move toward de Gaulle’s vision of a “Europe of Nations”, although with defence firmly under NATO’s umbrella.

Policy harmonisation would occur only where member states see a clear competitive advantage in doing so, and Europe would otherwise be characterised by ‘regional state anarchy’. Regional bodies would probably see reform, and the European Convention on Human Rights might be among the first to be effectively neutered and recast to fit less progressive values, especially regarding regulation of migration and due process.

In this more fragmented regulatory space, the business environment would favour multinationals and large European corporations with enough capital and the capacity to navigate diverging regulation. The persistence of good relations with the US would ensure Europe is still the second (or third next to Asia) choice for big players. However, as supranational oversight weakens, income shielding through (legal) tax evasion could become increasingly feasible, with some states starting to engage in races towards the bottom.

With cutbacks to EU grants, subsidies, and loans, individual member states would see heightened competition for state aid. Supply chains could become more localised, and companies would in such a situation shift their focus toward lobbying local and national policymakers to secure favourable conditions.

We move on to Scenario B, characterised by a united EU and a reaffirmation of the transatlantic alliance.

How would we get there? Like in Scenario A, a change of course in the US would be required, but this would need to be coupled with a continued commitment among EU’s leadership to pursuing greater autonomy – in defence, security, tech, and innovation – and to do more to harmonise the internal market.

Current signals that make this outcome plausible are plentiful. For one, it’s not a given that high public support for the EU will dissipate even if current threats diminish. The encroachment of autocracy may continue to be a galvanising force for pro-EU sentiment. If outlier states continue to undermine EU policies that are otherwise universally pursued – Hungary’s opposition to support for Ukraine being the best example – we may see ‘core’ EU states take tougher means in their disposal, including the withdrawal from treaties in unison and the enactment of new ones, with or without contrarian governments included. Russia is also likely to be perceived as a foe rather than friend for the foreseeable future, regardless of whether relations normalise somewhat following a peace in Ukraine. Yet focus shifts further eastwards, and China is now perceived as the primary threat against a unified Western world.

What would Scenario B mean for people, policy makers, and businesses?

On a policy level, interest in strategic expansion of the EU would likely remain tepid as good relations with the US are revived, guaranteeing security to a relatively high degree. Institutional integration would continue, and a lack of major disruptions may enable more integration in health and social care policies, mostly as a necessity to address growing labour shortages. The axiom of “the US innovates, and the EU regulates” would largely hold true, although increased investments in infrastructure, clean energy, education, and R&D are pursued. However, without a strong strategic impetus to bet on European alternatives, dependence on mostly American tech would likely remain high.

Citizens could come to enjoy more seamless travel and “soft Schengen” perks beyond borders: cross-border rail passes, roaming-free 5G, and interoperable digital IDs that double as driver’s licenses.

As economic integration deepens, doing business across the EU could become easier, and an environment of low volatility may also incentivise investment. Talent acquisition would likely remain a struggle for small- and medium-sized companies as the US still outcompetes on salary and its re-stabilisation has made it once again the preferred destination for foreign talent. The internal market could see expansion to include more business-critical aspects like banking, making this scenario likely to be best one to be in for smaller organisations who want or need to expand.

Scenario C presents us with a more uncertain future for Europe in the world, but also one in which common goals are pursued effectively within the Union.

From the perspective of 2025, this is the ‘status quo’ scenario, with high internal support for the European project (public and political) but increasingly shaky transatlantic ties. Signals indicating a prolonged stay in this corner of the scenario matrix are all around. Amid tariff confusion, diplomatic flip-flopping, disagreements on Ukraine, threats on European sovereignty, and squabbles over DEI initiatives, it can be difficult to imagine a normalisation of EU/US relations anytime soon. We’re also witnessing a post-Brexit rapprochement between the UK and the EU, with 2025’s “reset of relations” perhaps marking the first step toward a reestablishment of the ruptured ties. Another development worth noting is the recent demonstration of enhanced collective defence and crisis preparedness, including in the form of the European Defence Fund, allocating €1,065 billion for collaborative R&D.

This doesn’t mean that things will stay the same, even if the overall trendlines endure.

A decade of turmoil, especially on EU’s frontiers, could revive belief in the European project, spur the development of a more robust pan-European identity, and support both increased cross-border movement and participation in EU democratic institutions. Yet this might also lead to further radicalisation of Europe’s populist cohorts.

On the policy level, we may see much more robust EU competencies – especially in defence and perhaps health – and an integration and harmonisation of policy. A key question will be whether the EU is willing to compromise on its rights and values agenda to increase competitiveness.

The UK may consider re-accession to the EU due to frayed relationship with US and continued isolation as efforts to realise a kind of “CANZUK” mobility pact fail.

The EU could begin considering a strategic expansion to bolster its security and global influence in an increasingly turbulent international arena. Accession talks might accelerate – even if candidate countries have not fully met all the criteria, especially on human rights and institutional corruption – with former Yugoslav nations, Albania, Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine, and possibly even Turkey moving closer to formal EU integration.

At the same time, EU member states with overseas territories might seek to retrench decision-making authority under the pretext of national security. France could move to limit the autonomy of its territories in the South Pacific and North America. Denmark might exert pressure on Greenland and the Faroe Islands to deepen ties with the Union, while Norway – though not an EU member – may increase its strategic presence on Svalbard.

In a parallel effort, the EU might intensify its bid to renew and reposition Euro- African relations. EFTA countries could face increasing pressure to either fully commit to the EU project or risk marginalisation – what some might call a “believe it or leave it” moment.

Looking further abroad, the EU may seek to forge stronger alliances with likeminded partners such as Canada, Japan, Mercosur nations, ASEAN members, and others, as part of a broader strategy to create a resilient network of democracies and economic allies.

In business, a shift towards home-grown solutions would spur the growth of European tech industry, but it would still struggle to compete fully against established US giants. Some may begin looking to China for new kinds of partnerships as a counterweight to US, although this is highly uncertain. Businesses would increasingly be expected to uphold “European values” in their business practices, marking clear alternatives to the practices of their international competitors. Industrial policies would permeate all sectors and all themes, with companies and industries coordinating initiatives and investment plans with Brussels.

Our final scenario, MXGA, combines a fragmented Europe with a more transactional global environment and a further breakdown of transatlantic ties. It’s the one scenario with a recent historical analogue to draw from, yet plenty of contemporary signals pointing in the direction of this outcome can be found. Contestation over the legitimacy of European human rights, mentioned in Scenario A, also applies here. Should trust wane in the EU’s ability to uphold the region’s security through defence or migration, these priorities would face public backlash, falling into the exclusive purview of nation-states.

Finally, the recent surge in support for nationalist and nativist parties, including an election win in Poland in June 2025, increases this scenario’s plausibility. Parts of the far left in some countries have also signalled a willingness to subvert existing EU treaties if found to be a barrier to pursuing policies of social and climate justice.

Scenario D sees the surge of populist and sovereignties movements lead to increased democratic participation in national politics at the expense of EU institutions, which are increasingly eschewed. The resulting policy divergence between countries could lead to a limitation in inter-European mobility as well as variation in individual rights and freedoms.

In this scenario, the dismantlement of the EU could come to be seen as a genuine possibility for which Brussels might need to begin planning. A future majority in the EU Parliament, along with several heads of state, could call for referenda on a new set of treaties aimed at reducing the Union to its “bare bones” functions – trade, security coordination, and little else.

Some regions might respond to the EU’s fragmentation by pursuing deeper forms of integration among themselves. The Nordic countries, for example, could investigate a more formalised political union, potentially elevating the Nordic Council into a policymaking organ. Baltic states might be eager to join such a bloc, viewing it as a way to sustain economic growth targets and preserve minimal security guarantees.

Predominantly Slavic countries could seek closer ties with actors outside the EU and EFTA. Some might draw closer to the Russosphere as Russia’s past actions in Ukraine are gradually forgotten, reframed, or ignored – particularly in the absence of a compelling alternative Great Power presence in the region.

NATO might, by this point, be effectively defunct. In response, Germany and Poland could pursue the development of tactical nuclear arms, citing a deteriorating security environment.

With the EU’s regulatory capacities diminished, member states might increasingly adopt divergent policy approaches. The idea of human rights law could come to feel more like an abstract ideal than a coherent system of enforceable norms, with monitoring mechanisms eroded and legal obligations largely symbolic.

Global supply chains could give way to more regional and ‘friend-shored’ setups to better insulate local economies from international disputes and disruptions. Bilateral and regional trade agreements would now dominate – including with states such as China, and even Russia – sidelining the WTO, which could lead to increasing trade concentration, where countries trade with fewer partners, and privilege those with which they are in closer geopolitical alignment. In the absence of a united EU to draw investments from, countries could look elsewhere. Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative could make further inroads into Europe.

With the decline of the EU and its regulatory framework, state aid may also become both more widespread and more politically justifiable, framed as a necessary response to external pressures and internal instability. This shift could lead to intensified competition among domestic companies, while also fueling accusations of favouritism and corruption, particularly in the absence of strong oversight mechanisms.

Whatever path Europe will follow, its people, leaders, and businesses will share a common challenge in turning foresight into action. Scenarios only sketch out the contours of possible futures; signals will drift, new drivers will emerge, and the axes themselves may need to be redrawn. But through this rehearsal of future divergences, we reduce the surprise factor and, hopefully, widen the margin for experimentation, curiosity, and adaptability in the present. Treat the four futures offered here as a living framework – one that can be revisited once the next shock election, geopolitical crisis, or breakthrough nudges us toward a new quadrant. Scenarios, when we think with them, improve our ability to anticipate rather than react and remind us that while the future is not predictable, it does leave clues in the present – plenty, if we care to look.

This article was first published in Issue 14: European Futures