In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

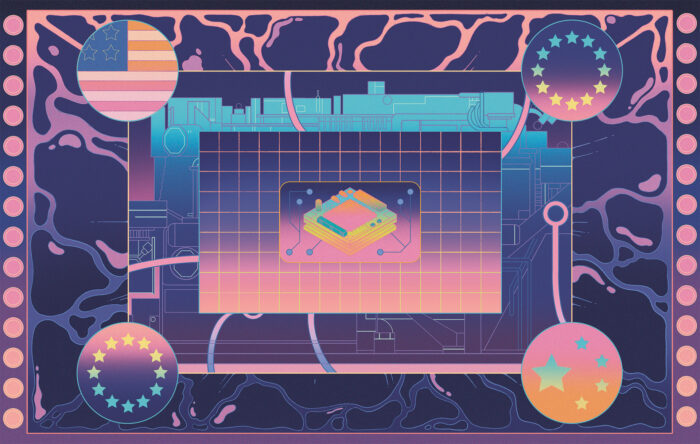

From CIA-funded think tanks in the 1960s to the EU’s strategic foresight efforts today, futurism in Europe has served to safeguard the liberal order against the perceived dangers of radical mass politics. As the discipline becomes more participatory, could the shifting will of the masses become a disrupting force?

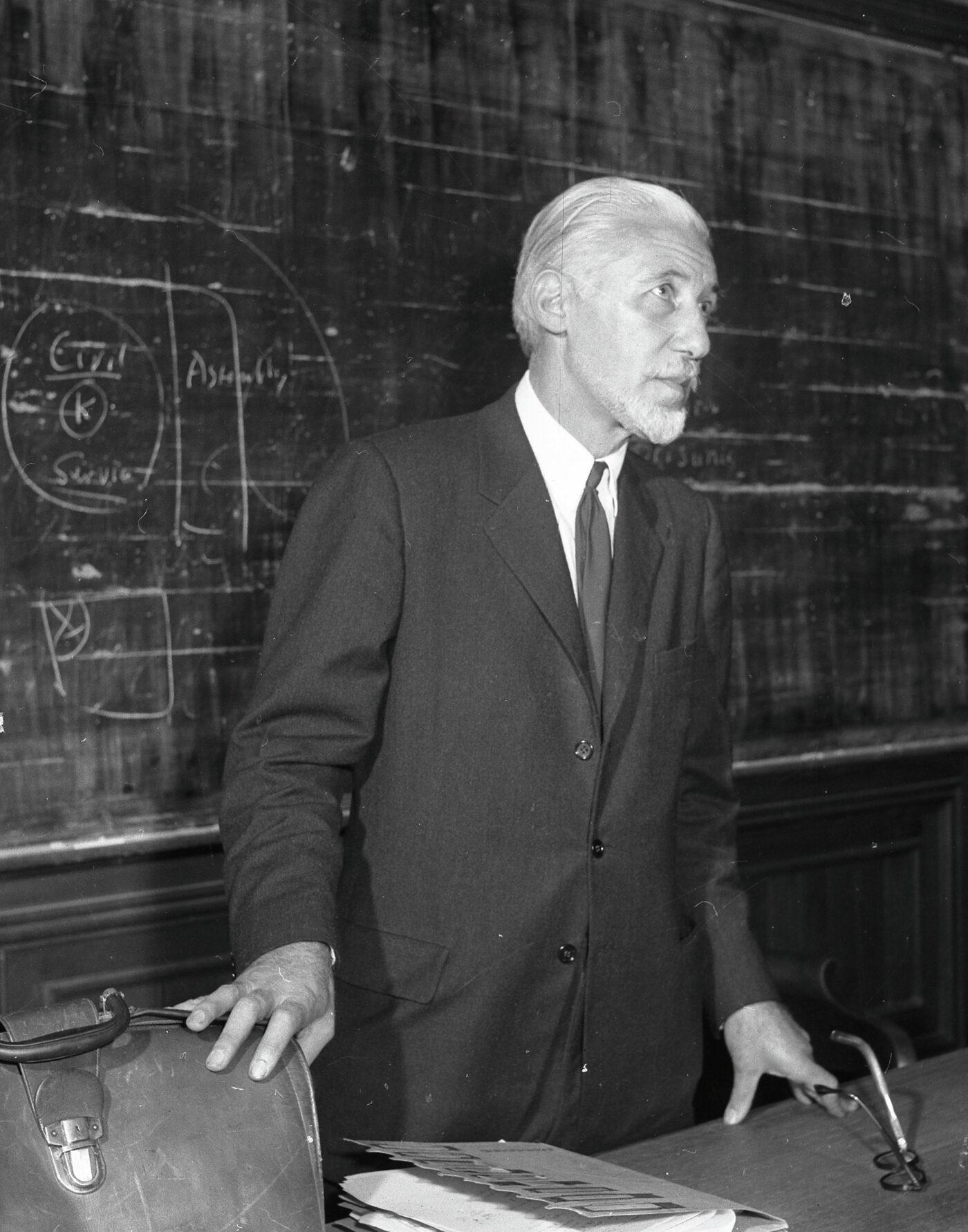

Photo: Bertrand de Jouvenel, circa. 1960. USIS-DITE/BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Europe’s first futures think tanks sprang up in the 1960s. They were born out of a top-down effort to develop images of the future that could counter the appeal of Marxism and safeguard the liberal order from the threat of radical mass movements. Today, futurism – now in the form of foresight – is once again mobilised in the service of liberal democracy. But it is now much more anchored in public participation, making the shifting will of the people a potentially disruptive force.

In February 1936, the French philosopher and journalist Bertrand de Jouvenel sat down with Adolf Hitler in Berlin. He was interviewing the German chancellor for the journal Paris-Midi.

It was not a great time to be a liberal in Europe. Former democracies had turned fascist, and Russia was firmly under Stalin’s dictatorship. Democracy looked weak, and in terminal decline. The few democracies still left faced threats from outside, from Europe’s new strongmen, and from within, as dissatisfaction took hold not only among the masses but among parts of the European intellectual elite as well.

De Jouvenel was a perfect example. The conversative philosopher not only believed that dictators like Hitler could be reasoned with. Like some other conservatives of his time, he was at this point sympathetic to fascism. Liberal Europe had grown ‘soft’ and ‘feminine’, he believed, and its people had become unwilling to take on painful tasks. Democracy was in decline, but in Hitler’s Germany, de Jouvenel saw a vitality, perhaps a model direction for the future of Europe.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberIn de Jouvenel, Hitler probably saw nothing more than a willing stooge. When delivering his multi-hour monologues to the German people, Hitler would rail against the French. With de Jouvenel, his tone was amicable and conciliatory. His motive for engaging in the talk was likely to dissuade France from ratifying the Franco-Soviet Pact agreed to a year earlier. He made an insincere offer of friendship to Germany’s rival, which de Jouvenel carried on in his article:

“Today France can if she desires end forever the ‘German peril’ that your children from generation to generation learn to fear […] You have before you a Germany nine-tenths of which supports its chief, who says ‘let us be friends’.” (English translation via the Madera Tribune)

It wasn’t the philosopher’s finest moment. A week after the interview was published, German troops marched into the Rhineland, breaking with the Versailles Treaty and starting down a path of offenses and incursions that would culminate in the invasion of Poland in 1939. De Jouvenel, not knowing the future, fell for Hitler’s tricks.

It’s perhaps ironic that he would later go on to become one of Europe’s foundational figures in futurology – the new science of studying and anticipating the future. In 1960, de Jouvenel established Europe’s first futures think tank, the Futuribles International. In 1962 he published the book The Art of Conjecture, now widely considered a classic of the discipline.

At this time, futurology had become synonymous with US think tanks like RAND and the Hudson Institute, where figures like Herman Kahn – famously an inspiration for Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove – were using scenario planning and other newly devised techniques to anticipate and manage the unruly future. RAND researcher Olaf Helmer had declared that futurology enabled scientists to “deal with socio-economic and political problems as confidently as we do with problems in physics and chemistry.”

When de Jouvenel helped bring the discipline to Europe, he did so with the aid of powerful friends. Futuribles got started with an endowment from the Congress of Cultural Freedom, a CIA-funded organisation based in West Germany enlisting European social scientists aligned against Marxist thought. It was part of a bigger push that historians have described as a kind of Marshall Plan for the European social sciences.

This was the war of ideas in which futurology in Europe found its footing. The Congress of Cultural Freedom and other influential backers like the Ford Foundation – which channelled CIA money to the continent – wanted to foster a kind 69 of epistemological counterpunch to the Marxist vision of the future that held such sway over European intellectuals.

One emblematic point of strife in this struggle over the future was a disagreement that arose about a decade later, with the establishment of the World Futures Studies Federation, over the inclusion of the plural ‘s’ in the organisation’s name. To futurists in Ceausescu’s Romania, where an early conference was held, the notion of a future outside a communist one was unthinkable, and so the ‘s’ became a point of contention. It was removed only to reappear in 1990. “In Russian the word ‘future’ exists only in the singular”, the Soviet futurist Igor Bestuzhev Lada once wrote.

In the West, by contrast, futurologists envisioned multiple possible outcomes through scenario thinking, but even so, the goal was ultimately the same: use the study of the future as a tool to stabilise the present. It was explicitly understood that the future was an ideological battleground, and that anticipating it was not just an academic project, but a political one as well.

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereThe initial mandate of Futuribles was to tackle how the potentially chaotic and dangerous pluralism of mass society could be somehow rationally managed. De Jouvenel, who had long since abandoned his fascist leanings (supposedly after Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938), was still a conservative quasi-monarchist at heart. The threat, for him and like-minded futurologists, was whatever radical impulses could come bubbling up from the grassroots. Accordingly, the masses were viewed as suspect rather than a source for alternative visions. He considered expert conjecture, rather than deliberation rooted in democracy itself, the bulwark against this threat of mass psychosis.

In her book The Future of the World (which I have paraphrased from here) the historian Jenny Andersson argues that this “managerial impulse” made the future a more-or-less predetermined place – both in West and East. Futurology had an analogue in the Soviet Union, where early ambitions of imagining alternative paths for the future of socialism eventually devolved into prognostika, a technocratic management tool for state planning.

Something new emerged from the late 1960s and into the 1970s, Andersson argues, with the formulation of more globally oriented futures projects like that of the Club of Rome. But such attempts were few and far between. Finally, from the 1980s and onwards, futures and foresight became much more embedded in corporate strategy – and by consequence became less about shaping the future to safeguard a political order, and more about helping organisations and companies survive and thrive.

In more recent years however, futurism as a political project has had somewhat of a renaissance in Europe. Since 2019, the EU Commission has ramped up its foresight activities and has begun integrating foresight methods closer to policy development around issues like technological autonomy and the green transition. The Commission has published annual strategic foresight reports since 2020 that point to foresight’s role not only in exploring possible futures – what may happen – but also in helping the EU shape a prefrable version of it – what ought to happen.

This future is obviously one with a stronger (not weaker) EU, and more (not less) democratic participation. It is also one that ought to feature a faster (not slower) green transition and a more socially and culturally cohesive Europe. These are all things that have come to be associated broadly with the European project. While it may not be couched in revolutionary language, there’s a clear normative thrust present in many parts of EU foresight.

This means that futures thinking in Europe today is still, to some extent, a political project, as it was for de Jouvenel and the first European futurologists. A key difference between now and then is that the legitimacy of EU foresight is anchored in public participation rather than solely in the deliberations of expert futurists. In 2022, for example, the pan-European Conference on the Future of Europe was held, which included citizen-led debates, scenario-based discussions, visioning exercises, and the subsequent development of long-term policy recommendations. Other similar initiatives have used citizen engagement to create ‘bottom-up’, grassroots images of alternative futures.

At the moment, popular sentiments seem to broadly align with the vision of a stronger EU. A 2025 Eurobarometer survey found public support for the European Union to be at 74%, the highest ever recorded. Yet even as public support for the EU surges, the spectre of the unruly masses continues to present a latent threat to the liberal European project.

The Commission’s 2023 Foresight Report acknowledges the risks posed by Europe’s “geography of discontent” – zones of economic stagnation where euroscepticism is rampant. This discontent manifests in the form of growing anti-elitism, extremist, autocratic, and populist movements drawn to cults of personality, and an increasingly silent citizenship less interested in general democratic life and more prone to isolate themselves on social media.

Crucially, this geography of discontent is not merely the result of external forces outside the EU’s control. Rather, it has emerged partly because of unintended consequences of the Union’s own policies: EU-mandated austerity measures following the Eurozone debt crisis, environmental and climate policies provoking rural backlash, the migration crisis of 2015 becoming a political flashpoint.

Europe’s foresight project seeks to anticipate and shape progressive, future-oriented policies, and to do so building on a mandate from a public that seems currently to be broadly aligned with these goals. It’s a symbiotic relationship, for now at least. But it does invite the question of what might happen if we see a dissipation of this high degree of public support which is currently galvanised by the war in Ukraine and transatlantic tensions. Another crisis similar in scope to the 2015 migrant crisis perhaps, or growing opposition to the green transition and its impact on our daily lives, could spark new waves of dissatisfaction.

If more Europeans turn away from Europe and embrace a vision of the future that contradicts the goal of a closer Union, or perhaps one that doesn’t include the EU at all, foresight as it is enshrined in the EU could paradoxically become anti-democratic and anti-liberal too.

Foresight, by consequence, finds itself in a balancing act: to commit to universal values anchored in liberal institutions – and risk backlash – or attempt to be value neutral and go where people want to take it – and risk losing direction. Foresight in the EU has largely taken the first approach. But in a world where the Western liberal order is withering, the consensus around which values should be considered universal come under fire as well. Should the role of the futurist be to champion one vision, or to map them all and let the people decide?

This article was first published in Issue 14: European Futures