In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Oscar Wilde famously believed that the things we find in the world are not really there. Instead, they are things that art has taught us to see. Although there had always been fog in London, Wilde said, the city’s residents only noticed its beauty and wonder because “poets and painters have taught the loveliness of such effects”. Put differently, art shapes our view of the material world surrounding us — including what we notice, value, or ignore.

The same is true for how we view and give shape and colour to the future, perhaps even more so than the material present. Unlike fog in London, the future doesn’t exist, and the concept of the future(s) being multiple rather than singular is not a fact of nature, but something that futurists have taught us to believe.

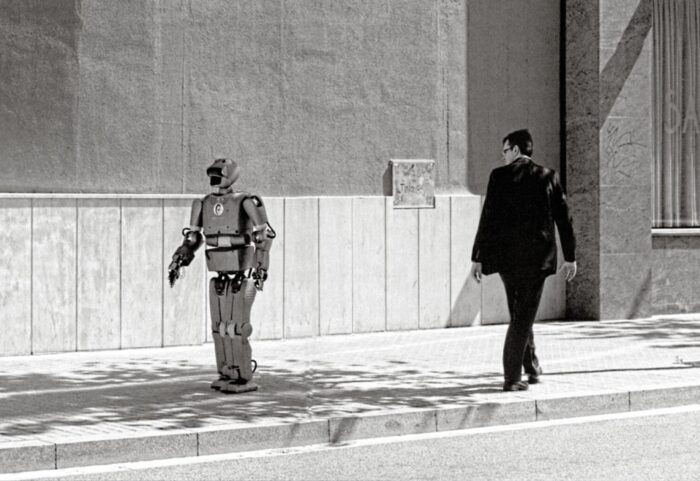

Yet futurists are rarely the ones who get to decide how our conceptions of these different futures are given colour and shape. As much as they might like the opposite to be true, they don’t have that kind of influence on the collective imagination. Art, on the other hand, does. Ask anyone to describe the future and most likely, their answer (whether hopeful or pessimistic, or a mixture of the two) will include predictions of technologies and concepts that have been explored in fictional worlds. Parallel digital dimensions, alien visitors, radical social change, humanoid replicants, utopian societies, or dystopian breakdowns — whatever their hopes or fears are, it is likely that their ideas, or at least parts of them, were informed by creations of art and media.

When it comes to the future, art rarely predicts, but it has a profound ability to expand our understanding of the realm of possibility. And the most impactful of these future images have incredible staying power in the collective psyche. While this is true for a lot of art, few art forms have bent our conceptions of what is possible as consistently and decisively as science fiction, a genre that is situated between current reality and future possibility.

The examples of this dynamic in action are many. Tim Berners-Lee is famously said to have found inspiration for his invention of the World Wide Web in science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke’s short story Dial F for Frankensten, in which a network of telephones develops consciousness and takes over the world. Supposedly, reading the story as an adolescent created such an impression on Berners-Lee that he developed an interest in technological networks which persisted into his adult life, where he would eventually enrol at MIT and, later, lay the groundwork for the World Wide Web while working at CERN in Switzerland. After becoming reality, the web then led to a new wave of speculation among writers including Neal Stephenson, whose novel Snow Crash coined and described the concept of a ‘metaverse’ and is now required reading at the Facebook-owned virtual-reality company Oculus. Mark Zuckerberg, of course, recently unveiled his plans to transform Facebook from a social media company to a ‘metaverse company’, with a fifth of its employees reportedly working to make that happen. And Stephenson, by the way, now works for VR-developer Magic Leap.

Several questions arise from tracking the roots of the feedback loop between fiction and innovation, and how the ideas formulated by yesterday’s titans of sci-fi have helped shape the products we use today. What if, for instance, the required reading at Oculus and other technology companies not only included novels set in a tech-saturated future, but also literature that engages directly with questions of situated knowledge and the historical specificity of the production of technology? To what extent could our current challenges with algorithmic bias in AI and elsewhere be less pronounced, if no-one involved in the design process suffered from the illusion that products and software can ever be built to be bias-free — that no-one can have a ‘view from above, from nowhere’, as feminist theorist Donna Haraway puts it?

While we ponder these ‘what-ifs’, the feedback loop between fiction and innovation only grows in strength, with corporations like Google, Microsoft, Apple, Visa, Ford, Pepsi, Samsung, Nike, Ford, Hershey’s, Lowe’s, and Boeing now employing sci-fi writers to do ‘sci-fi prototyping’ to help them get a better sense of the kinds of futures in which their products and services might be used. This list also includes the global professional services firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), who published a paper in 2017 describing the potential for business innovation that they believe could be unlocked through the imaginative power of science fiction: ‘Fictional worlds allow new products and their use to be explored without the strictures of money or technological capability hampering creativity’, they write.

So, what exactly are sci-fi prototypes? Usually, they come in the form of short pieces of fiction with narratives, a gallery of characters, conflicts, and resolutions — all the things any good story has. A prototype may have different uses depending on the commissioning client. It could, for instance, be used for ‘threat casting’ to manage risk and stop certain undesirable futures from occurring. Or it could be meant to serve as inspiration for the how, i.e. in which situations and for what purpose a so-far undeveloped product could be used by individuals in a future that is different from the present. In the most successful and compelling cases of sci-fi prototyping, the stories can serve as inspiration for developing further blueprints or actual product prototypes.

Although the end-goal of sci-fi prototyping is often product development, it’s not only the corporate world that is hiring writers to help them chart the way ahead. The military too, has now begun commissioning works of science fiction to inform their long-term decision making. A 2017 strategy paper from NATO titled “Visions of Warfare 2036” details how military strategists can use science fiction to ‘discover, from the minds of professional writers, new tech, novel use of existing tech, new doctrines’ and to ‘allow open discussion, using strength of storytelling, about the future character of war’.

Art is a lens through which we can explore uncertainty and examine both the need for and limitations of human agency in an increasingly complex future. This publication explores the role of art as a unique and invaluable form of futures inquiry and showcases how art and futures studies interrelate and shape each other in various ways, drawing on examples and cases from international contemporary art, curators, art institutions, and futurists.

Download the report for free hereEvidently, there is a growing realisation of the potential for creative storytelling to inform the strategic choices of many types of companies and organisations. Yet this instrumentalisation of literature to serve the purpose of multinationals and militaries is not exactly uncontroversial and will likely leave a sour taste in the mouth of some writers and readers. After all, can science fiction retain its edge and integrity if it has become an innovation sandbox for corporates and military agencies — the kinds of institutions that often take the role of villains in sci-fi literature?

Such criticisms notwithstanding, there can be no question of the growing influence and success of the emergent ‘sci-fi industrial complex’. Indeed, one of the more prolific companies in the field, the LA-based innovation agency SciFutures — whose clients include VISA, Ford, Colgate, Intel, and the US military — boasts a network of ‘more than 300 sci-fi writers, visionaries and experts’. Their prototyping comes not only in the form of short stories, but also graphic novels, motion comics, interactive web narratives, animated videos, and augmented reality content.

In some ways, sci-fi prototypers are doing what futurists have been doing since the 1960s — that is, creating fictional future worlds (scenarios) designed to prompt debate and provoke new decision-making. But there are some key differences between sci-fi prototyping and futurist worldbuilding as well. The scenarios used by futurists are, by design, multiple. They emphasise the range of forces outside our control that might swing the future in one direction or the other, which is why they come in sets (most often of four). Furthermore, scenarios tend to be mostly depopulated, with little room for individual agency. When scenarios have people in them, they act and think in groups (e.g. as population segments or ‘consumers’). As such, scenarios can sometimes lack the things that make fiction so appealing: immersive and engaging stories and characters that give the world colour and make it accessible and believable to the reader.

Could futurists learn something from the way sci-fi prototypers bring the future to life? Definitely, and perhaps we all could. After all, we humans are not purely analytical creatures. We need stories to make sense of the world and the futures ahead.