In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Lab-Grown Meat

Caught between venture-capital and sustainability

A part of our Scenario Archives series

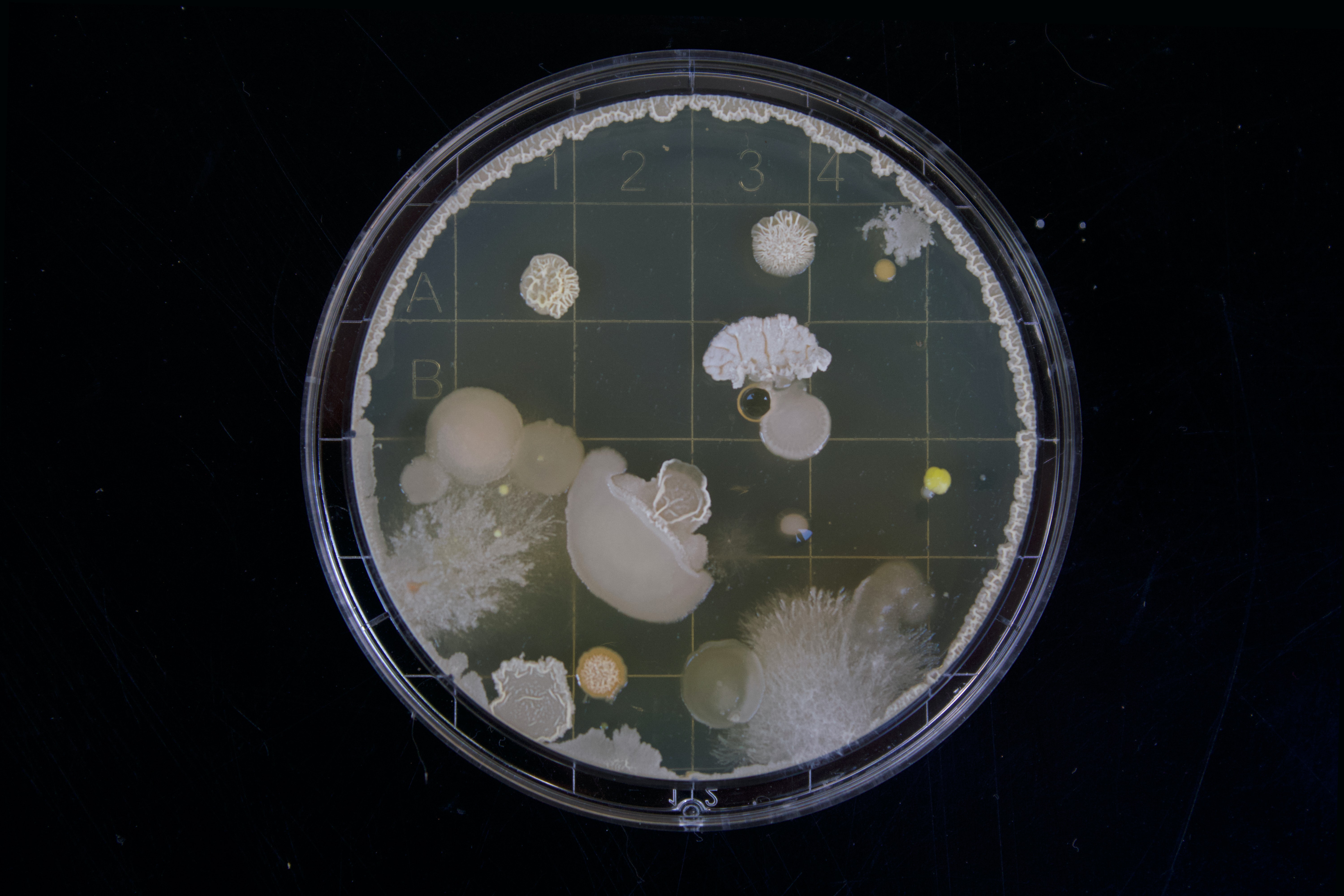

A petri-dish filled with red mush. The blend consists of thousands of mammalian cells, cultivated by scientists who are trying to grow meat in laboratories instead of raising and slaughtering animals. Could this be the best thing that has ever happened to carnivores – a way to enjoy meat products in a (presumably) more sustainable way?

The incorporation of meat and marrow from large animals was the first major evolutionary change in the human diet, and occurred at least 2.6 million years ago. To begin with the animals that supplied the meat came from the forests, then from farms, and in industrial times from factories. In the future, meat might come from a lab. To satisfy the increasing demand among the growing human population for food, lab-grown meat (also called in vitro, artificial, clean or cultured meat) is presented by its advocates as a good alternative for consumers who want to be more responsible but do not wish to change their diet.

Growing meat without the need to slaughter animals is not a new idea. Winston Churchill envisioned back in 1931 that in 50 years’ time, humans would “escape the absurdity of growing a whole chicken in order to eat the breast or wing, by growing these parts separately under a suitable medium”. Fast forward to 2021, where the industry of lab-grown meat is rapidly growing. Funding soared last year, with investments growing sixfold and dozens of new companies entering the race to bring the first lab-grown meat products to market.

At first glance, the formula for lab-grown meat is quite simple: Take a biopsy of cells from an animal, isolate the stem cells and feed them nutrients so that they start to proliferate. Then transfer them to a bioreactor, where the cells turn into muscle cells, start to fuse together and form strips of muscle fibre. Perfect the process and you could possibly grow hamburgers, and, eventually, steaks to feed the hungry carnivores of the planet. That’s the brief version, at least. Why would someone swap their Big Mac for something that looks like it belongs in an episode of Black Mirror, you might think? The World Economic Forum makes it clear: There is a need for radical transformation towards a global land use and food systems that serve our climate needs. As the planet’s population heads towards 10 billion, the current trends in meat consumption and production cannot be sustained. In the future, lab-grown meat might replicate the taste and consistency of traditional meat. As the industry for lab-grown meat is growing, scientists are debating whether it could potentially exacerbate or ameliorate climate change.

Scientists know the impact of cattle on the environment: The global livestock industry produces more greenhouse gases than the exhaust from every form of transport on the planet combined. In fact, livestock production is responsible for around 15% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. The world’s three biggest meat companies emit more greenhouse gases than the entire nation of France. But when it comes to estimating the impact of large-scale production of lab-grown meat, it’s not as straightfor-ward, because, well, the industry does not yet exist. But that does not stop researchers from modelling the potential emissions of the future lab-grown meat industry.

Hanna Tuomisto is an associate professor in sustainable food systems at the University of Helsinki. For over a decade, she has been involved in research projects that attempt to estimate the possible climate impact of lab-grown meat. She says that the first research papers were more optimistic and forecast a low environmental impact, mainly because the models involved the use of a cultured medium – the fluid that makes cells grow – made of cyanobacteria, which has a low environmental impact. More recent research, however, has been based on the current production methods, in which the culture medium is foetal bovine serum and plant-based ingredients.

“The key message with regard to the environmental impact of lab-grown meat is that it depends a great deal on the type of nutrient sources used and the type of energy used for the bioreactors in a large-scale facility,” says Tuomisto.

Creating these models before a full-scale industry exists could prove useful in order to identify the hotspots and main sources of negative environmental impact. This data could be of assistance to companies who wish to develop the technology, Tuomisto explains.

Some researchers speculate that, depending on the efficiency of the production process, the rise of the cultured meat industry could actually have a more negative impact on climate change than traditional beef production. In 2019, a group of researchers from Oxford University looked at the long-term climate implications of lab-grown meat versus meat from cattle. The scientists’ climate model found that in some circumstances and over the very long term, the manufacture of lab-grown meat could result in more global warming. One issue is the longer-lasting impact of carbon pollution versus methane gas pollution. In their study, the scientists looked at the temperature impact of the GHGs involved for up to 1,000 years into the future. The various greenhouse gases behave differently once emitted into the atmosphere. Methane has a much greater warming impact than carbon dioxide – however, it only stays in the atmosphere for around 12 years, whereas carbon dioxide persists and accumulates for millennia. If the future industry of lab-grown meat ends up producing a lot of carbon dioxide pollution, it could be even more damaging for the planet than emissions from beef and cattle production.

“For lifecycle assessments, we usually project the impact for the next hundred years. The Oxford study projects the impact for the next 1,000 years, which doesn’t necessarily make much sense, as we should be more concerned with the climate impact over the next 30 years. It’s almost like saying that the climate impact of beef isn’t too bad because most emissions come from methane. We know that methane does a lot of damage during the 12 years it remains in the atmosphere, and that should worry us.

“Methane is the second-largest contributor to climate change, and emissions are primarily driven by the number of animals – there are roughly one billion cattle around the world. Beef production is considered the worst offender, with cattle emitting methane and nitrous oxide from their manure and their digestive processes. Lab-grown meat is not going to help us with urgent climate change. Emission reductions need to happen now. We cannot wait for this tech to mature and for it to possibly solve our climate problems. There are other options that would serve us better, such as reducing livestock production and choosing alternatives that are currently available, like plant or fungi-based options,” she says.

Half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture, and livestock accounts for almost 80% of this. Generally, livestock is thought of as being damaging to wildlife and having a negative impact on global biodiversity, but this is not always the case, as there are studies showing that grazing can sometimes have a positive impact on wildlife. If meat production is reduced, it would free up land which could potentially be used to reduce the carbon footprint.

“Ideally, we would plant trees to mitigate carbon footprint, but it’s more likely that the land would be used for something else, like intensive crop production. Grazing livestock have a role in biodiversity conservation, which would also be impacted,” says Tuomisto.

Tuomisto and her research group are now investigating the broader impact of what could happen if developed countries switched to partially consuming lab-grown meat, such as how it would affect the total energy use and land use on a national level. The research group has also looked at some unexamined consequences of reducing beef and cattle production. There are numerous by-products from beef production, including pet foods, chemicals and fertilizer.

“We need to consider how we would replace these products, and the environmental impacts of this,” says Tuomisto.

Despite the promises, no one has yet produced lab-grown meat for sale to the general public, but they are getting closer. In December 2020, the industry received a major boost when Singapore became the first country in the world to grant regulatory approval for the sale of lab-grown meat: a cultured chicken nugget product made by US-based Eat JUST. Tuomisto thinks this might be misleading and give people the impression that the technology is ready for large-scale production.

“We don’t know what they are actually producing, it’s all part of a chicken nugget so the texture of the meat is unknown, it could be just cell slurry. We know that they are currently using a foetal bovine serum to culture the cells. This is both expensive and makes it difficult to scale up because the supplies are low.”

She explains how the serum is harvested from pregnant cows during slaughter. If one of the main ideas of lab-grown meat is to take the animal out of the equation, it would be best to avoid this serum.

“You could possibly make chicken nuggets from plant-based proteins and make it taste like the real thing. So does it make sense to put all this effort into an energy-intensive process of cultivating animal cells if you could obtain similar products by using plant-based proteins?” she asks rhetorically.

Plant-based alternatives such as Beyond-meat and fungi proteins such as Quorn have reached the mass market. Whether we will see lab-grown meat products in a supermarket soon is questionable. Before a novel food product can hit the shelves, it needs to be approved by the European Food Safety Authority – a process that could take years, according to Tuomisto. She believes it will be a lengthy process before lab-grown meat can be approved for sale in Europe.

“Maybe we will see a niche product on the market in 10 years’ time. It will probably be similar to the chicken nugget offered by Eat Just. I don’t see large-scale production happening in the next 10-15 years,” she says.

The advocates of lab-grown meat believe it will be able to replicate the taste and consistency of meat and therefore offer the “real deal” compared to other substitutes. Some of the biggest conven-tional meat companies in the world have invested in lab-grown meat: The meat producer Cargill has backed Aleph farms, an Israeli start-up known for unveiling the world’s first lab-grown steak back in 2018, while Tyson Foods has backed Upside Foods, a start-up working on bringing lab-grown chicken to a dinner plate near you.

The world’s first lab-grown hamburger was tasted at a high-profile press conference in London in 2013, which was also broadcast live on TV. The hamburger, created by Dutch professor Mark Post, a physiologist at Maastricht University, was described by those who tried it as dry and rather tasteless.

The meat contained only proteins and hardly any fat. That is still the case with lab-grown meat, as it’s made from muscle cells. Fat would need to be cultured separately and added to the product. This represents a challenge in replicating the consistency of meat, but also an opportunity to reverse-engineer meat in a way that could potentially be healthier. In theory, scientists could model types of meat that contain healthy fats, added nutrients and no cholesterol. But there are still hurdles to be overcome before the taste and consistency of lab-grown meat could be mistaken for the “real deal” – which is why many of the products currently being developed are minced or processed, like the burger. Scientists can create unstructured meat products fairly well because it’s basically a mush of meat. To replicate the taste and consistency of a steak is in a different league, and would require a serious amount of work to get the fat, cartilage and muscle cells into the right texture and composition.

The industry of lab-grown meat has major challenges to overcome before it can potentially disrupt the multibillion-dollar meat industry, but if lab-grown meat takes just a small percentage of this revenue, it would still be lucrative. Replacing meat with a proprietary product would be even more lucrative, which is what could happen once companies figure out how to make lab-grown meat in different shapes and forms.

“I don’t want to sound too pessimistic in terms of technological development – we will see innovations in this area. The start-ups present a very optimistic prospect, but I have talked to scientists who are developing this technology, and they give a more nuanced picture. There are still major obstacles that need to be addressed,” says Tuomisto.

The problem of estimating the environmental impact of lab-grown meat is obviously that we don’t know what large-scale facilities will look like. What we do know is that there is a need to curb meat consumption globally in order to reach the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. One of the key questions we will need to ask ourselves as a society is: Do we really need a tech solution to make this happen, or couldn’t we just cut back on meat instead?

This article was featured in Issue 63 of our previous publication, Scenario Magazine.