In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Leviathans of the Deep

How the breakdown of international collaboration in the Arctic

heightens the risk of a nuclear ‘time bomb’ scenario

Illustration: Sophia Prieto

One of the overlooked areas of inquiry in the geopolitics of the Anthropocene is what we might – for lack of a better term – call ‘broken world archaeology’. Put shortly, broken world archaeology concerns the present and future consequences of past human interventions into natural ecosystems. As an example, the ecological impact of the past sins of the British mining industry are felt to this day, as discharges from abandoned mines continue to pollute over 1500 km (3 %) of rivers in England. In India, the area around Bhopal still suffers from the consequences of the massive gas leaks from Union Carbide in 1984. And, as a result of increasing carbon emissions, the world’s oceans are now under the threat of acidification. As environmental investigations constantly remind us, human activity has left irreversible traces on the planet.

Nowhere are the threats posed by human disregard for the local ecology more pressing than in the Arctic, a region characterised by a somewhat limited resilience in the face of oncoming disturbances. Because of the cold temperatures, oil spills in the region are notoriously difficult to clean up and are therefore likely to remain for years. Other significant contaminants include metals such as mercury and lead, as well as persistent organic pollutants including DDT, PCBs, and dioxin. But the greatest interventional threat to Arctic ecology (apart from the overall process of anthropogenic climate change) undoubtedly comes from its history as a site for nuclear contamination. During the cold war, the archipelago of Novaya Zemlya was used a nuclear testing site for the largest of the Soviet nuclear bombs, and the closed naval base in Gremikha Bay on the Kola Peninsula is still home to 50 or so decommissioned nuclear reactors. This makes the peninsula the most radioactively contaminated region on the planet. According to Norwegian environmental organisation Bellona, more than 17,000 containers of Soviet-era radioactive waste exist in the Arctic.

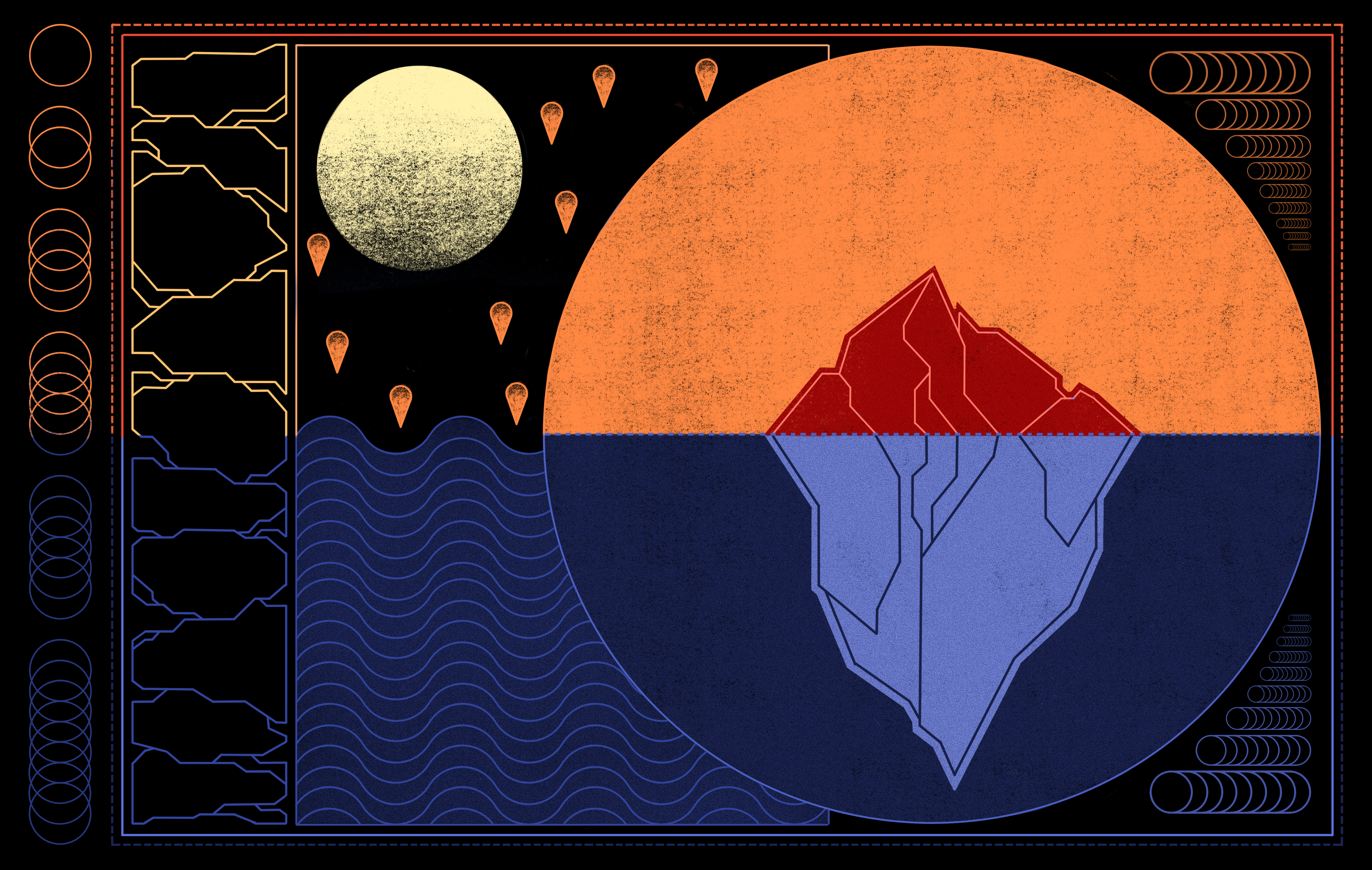

All of this, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. The greatest environmental headache in the region by far is the four sunken nuclear submarines placed at various locations at the bottom of the Barents and Kara seas. Perhaps the most alarming case is that of the K-27, a prototype ‘attack submarine’ that was commissioned into the Soviet Northern Fleet in 1965. K-27 had two experimental liquid metal-cooled nuclear reactors – a design which had not been utilised before by the Soviet navy. In May 1968, a leak in one of the reactors released radioactive gases into the engine room causing a high contamination of gamma rays and thermal neutrons. The inexperienced crew were inadequately prepared to handle this crisis and realised too late that the reactor had suffered from extensive fuel element failures. By the time they gave up their attempts to repair the reactor at sea, nine crewmen had been fatally exposed to radiation.

K-27 was laid up on Gremikha Bay on June 20, 1968. Until 1973, various experimental projects were carried out aboard the submarine. In 1979, K-27 was finally decommissioned and during the summer of 1981, the reactor compartment was sealed. The K-27 was then towed to a special training area in the eastern Kara Sea and scuttled at Stepovoy Bay off the north-eastern coast of Novaya Zemlya, a fjord with a depth of only 33 meters – despite the requirement of the International Atomic Energy Agency that nuclear-powered submarine must be scuttled to depths no less than 3000 meters. A joint Russian-Norwegian expedition in 2012 concluded that the situation was stable and found no radioactive contamination in the water and soil surrounding the submarine. However, it was also reported that the rusting and decaying vessel is a nuclear ‘time bomb’ that may be reaching a critical level, with the worst-case scenario being an uncontrolled chain reaction occurring. This makes the safe dismantling of the nuclear reactor a matter of critical urgency. According to Rosatom, Russia’s State Atomic Energy Corporation, the plan currently is to raise the wrecks of both K-27 and K-159 (another Soviet nuclear submarine with a defective hull, which currently lies at the bottom of the Kola Bay, threatening the local fishing industry) no earlier than 2030. In the meantime, we all must hope for the best and expect the worst.

The horrifying tale of K-27 – along with similar examples of other sunken nuclear ‘time bombs’ (the K-159; K-278 Komsomolets; and K-141 Kursk submarines) – underscores the vital need for international collaboration in the Arctic. Historically, the recognition of this need was what gave rise to the doctrine of geopolitical ‘Arctic exceptionalism’, which has meant that the parties involved in the region have largely been able to contain other conflicts and prevent them from affecting a mutual maintenance of an ‘apolitical space’ of regional governance, functional cooperation, and peaceful co-existence. The doctrine, despite not always having been followed ubiquitously, has in the past 30 years or so played a central guiding role in ensuring that disputes are solved peacefully and by the rule of law.

Perhaps the most prominent legacy of Arctic exceptionalism was the establishment of the Arctic Council. Since 1991, this high-level intergovernmental forum has addressed issues of interest to Arctic nations (of which Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States are currently members) as well as the issues of interest to the indigenous peoples of the region.

Although Arctic exceptionalism has ensured cooperation around critical environmental issues in the past, it is now coming under increased pressure on several fronts. One is the looming spectre of anthropogenic climate change, which is expected to cause the melting of the polar ice caps and the opening of a Northern trans-Arctic Sea Lane connecting Europe with East-Asia. This creates new commercial opportunities for the shipping industry and possibly also for the exploration and mining of Arctic natural resources, although this issue remains politically contentious. At the same time, the opening of new sea lanes in the Arctic also removes some of the insulation that has so-far prevented direct confrontations between the region’s great naval powers. From a geopolitical perspective, the strategic importance of the Arctic is increasing, which may threaten any prospect of future mutual collaboration.

However, the most immediate threat to the long and hard-won mutual confidence built up in the region comes from the heightened geopolitical tensions between NATO and Russia. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has had a devastating effect on the working climate of the Arctic Council, which is now, apart from Russia, made up entirely of NATO member states. In March 2022, these seven NATO members issued a joint statement declaring that they would not send representatives to meetings in Russia for as long as the war in Ukraine continues. As part of their response, Russia announced its withdrawal from a high-level joint commission with Norway that seeks to ensure nuclear safety in the Arctic region. This means that the fate of many of the clean-up programmes that have been facilitated by this commission are now uncertain at best. This is a development that is both clearly detrimental to Russian-Norwegian relations and to their neighbours.

Indeed, the doctrine of Arctic exceptionalism is in imminent danger of breaking down entirely. In the event of its breakdown, the challenges posed by the widespread nuclear contamination in the region would only grow. This threat, along with the other transnational environmental problems which led to the formation of the Arctic Council in the first place will not disappear simply because we stop talking about them. They are here to stay, whether we like it or not. The major challenge of the coming years will therefore be to maintain and repair current relations to a level of confidence that may allow the Arctic Council to function with relative smoothness, despite whatever else might be going on in the rest of the world. It is a task which will demand the utmost diplomatic skills on behalf of the parties involved. And then we might need to hope that the Russians love their children too.

This is a featured article from our latest issue of FARSIGHT: A World Pulled Apart?