In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

The world’s most populated country is throwing their weight into the space race – but is India a genuine contender?

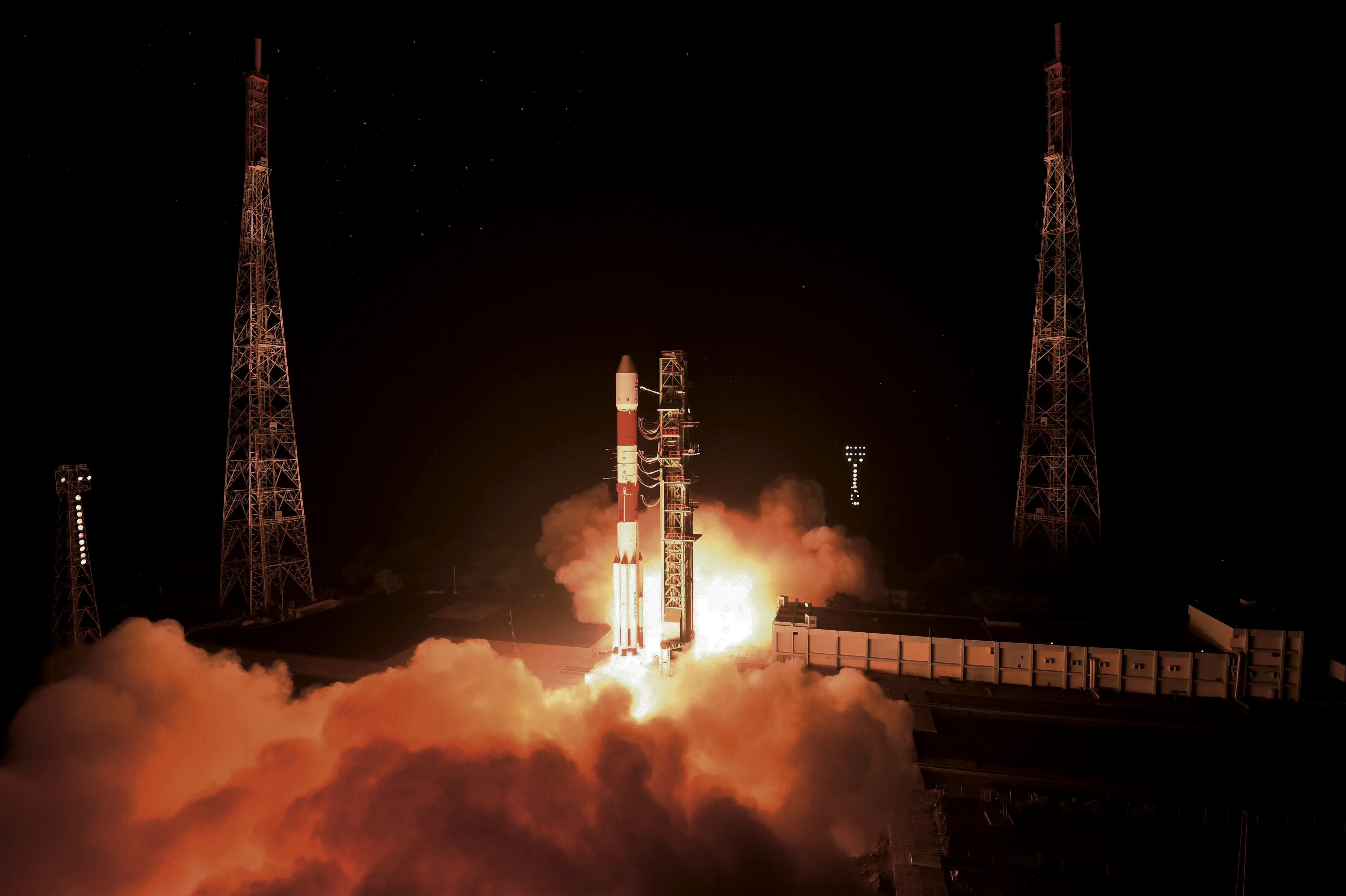

Image: ISRO

On 23 August 2023, India became the first country to land a craft on the Moon’s south pole – a historic moment in the history of space exploration. The Chandrayaan-3 (‘mooncraft’ in Sanskrit) landing was livestreamed to a rapt audience of millions. It’s seismic not only for India, but the world: scientists speculate that there may be vital reserves of frozen water and precious elements on this lunar ‘dark side’.

The whole endeavour is steeped in excitement. Not least, because India’s meteoric rise in space activity has put it shoulder to shoulder with China, Russia, the US, and Europe. In fact, Chandrayaan- 3’s celebrated touchdown came just three days after Russia said its first lunar mission in 47 years – also targeting the Moon’s south pole – had lost control and crashed.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberJust two months later, India sent another probe – the Aditya-L1 solar observatory – off without a hitch. The country is now the favoured launch destination for many international companies, while its Gaganyaan Human Spaceflight Programme is on course to send a peopled craft into orbit next year.

India’s rapid-fire achievements have attracted an explosion of media, political and investor interest. What does this mean for the future of the global space ecosystem? And as new space nations challenge the big-four power structure, could the implications for geopolitics be even bigger than for astropolitics?

India’s national space agency, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), was formed in 1962. It was the thick of the Space Race: five years after the USSR launched the world’s first successful satellite; four years after the birth of NASA; and one year after John F Kennedy upped the stakes by promising to “land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth” by the end of the decade.

But it wasn’t until 1980 that the ISRO made serious moves and put its first successful satellite Rohini into orbit, making India the seventh nation to achieve indigenous rocket launching capability. At the time, Western media sneered. The Washington Post’s write- up from December 1980 – headlined ‘India Hitches Its Future Development to a Homemade Satellite’ – describes how the ‘tiny’ Rohini satellite was ‘carried to an open field… in an all-wood bullock cart’, and ‘spun around the Earth for a full year, longer than expected, before falling into the atmosphere and burning up.’

But the following years saw ISRO develop its new satellite knowhow domestically, in uses spanning agricultural mapping, erosion monitoring, and telecommunications coverage. And, in the last decade, India’s space exploration has taken off in earnest. Today, it boasts one the world’s largest space programmes, designing, manufacturing, launching and operating a formidable spectrum of satellites, rockets and celestial probes. Even more advanced ventures, like human and robotic missions to low-Earth orbit and the Moon, have become frequent in Indian news.

How did the ISRO pull off all that progress so quickly?

Being pilloried by the West in the 1980s was a catalyst for autonomy. “At ISRO, the focus has been developing technologies to make best use of the available resources to meet national priorities, rather than competing with other spacefaring nations, with whom there was a vast technological gap,” says Tushar R. Phadnis, technical liaison officer at ISRO.

And India’s space programme is a now top political priority. “That the ISRO and the Department of Space is under the direct supervision of the Prime Minister is a big advantage. The government’s ambitious goals encourage the country to achieve ever bigger milestones,” says Phadnis.

But despite the ever-bigger milestones, the ISRO still lagged behind the programmes of the big four, where innovations in SpaceTech had accelerated exponentially in the 2010s. So in 2020, India made a major policy shift. The government gave the private sector access to the expertise and facilities of the ISRO – resources which it had closely guarded since the sixties.

In the three years since, private enterprises have piled in, bringing innovation and a competitive edge to India’s space endeavours. Its SpaceTech industry has exploded – and the investment community has leant in.

The private space sector has seen a significant rise in funding; compare a total of $35 million secured between 2010 and 2019, with the figure of $28 million secured in 2020 alone. And it has kept climbing – the space sector received $96 million investment in 2021, and $112 million in 2022. In the first half of 2023, it attracted $62 million – a 60% increase on the same period last year, according to a report published by the data platform Tracxn.

India has quickly turned into a global SpaceTech incubator. Abhay Egoor, CTO of one of the sector’s leading startups Dhruva Space, calls the government- private synergy the ‘most prevalent factor’ in driving innovation and attracting direct foreign investment.

“The space reforms have created tremendous opportunities. The industrial and academic ecosystem around the programmes of the ISRO, and the large talent pool of motivated and tech-savvy youth are providing ideal conditions for the rapid growth of the sector,” says Phadnis.

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereDr. Tirtha Pratim Das, director of the ISRO’s Space Science Programme, describes India’s tech-savvy youth as ‘the backbone of the ISRO’s achievements’. Leveraging this, the government has ramped up domestic competition with initiatives like the National Startup Award.

“When Dhruva Space won the award in 2020, it enabled us to showcase our indigenously developed space products to a global market,” notes Egoor.

The government’s ‘Make in India’ drive has also been a boon for the young SpaceTech industry: since 2014, the initiative has boosted the infrastructure for domestic manufacturing in 25 sectors. Meanwhile, India’s economic conditions, which enable particularly low-cost indigenous development, distinguish its space sector from those of the US, Europe, China, and Russia.

The upshot? India has suddenly become the world’s leading commercial satellite-launch hotspot. “The low cost is an important factor. Customers want to launch dozens of satellites instead of just one or two. It gives India an edge in the global launch industry and is a precursor to how the ecosystem can scale up massively,” says Dhruva Space CFO Chaitanya Dora Surapureddy.

Start-ups like Dhruva, Skyroot, Pixxel and Agnikul Cosmos are coming to the fore of India’s SpaceTech arena, turning the country into a plug-in-and-play destination for venture capitalists, and attracting people from various streams of tech and business. But for all its flashy achievements, the space business – especially the upstream segment – is inherently risky. It requires big, bold investments and patience: “the lead times for businesses to turn profitable are longer. Sustained availability of funding in the initial phases is a challenge,” explains Phadnis.

And, though India is resource-rich, it lacks the domestic capabilities to manufacture semiconductors – materials that are vital for producing satellite services.

“The necessity to import semiconductors places upward pressure on costs and acts as a barrier for private players to locally manufacture. Easing import would help in the short term, until semiconductor production kicks off in India,” says Egoor.

In 2023, Tacxn ranked India seventh in terms of funding within the international SpaceTech landscape. According to Phadnis, India aims to increase its share in the global space economy ‘by a factor of four’. What impact will India’s frequent, reliable and cost-effective access to space have on global astropolitics? Likely, India will see a groundswell of international partnerships that enable it to contribute to and benefit from more global space initiatives.

Encouraged by the success of industry privatisation, India may alleviate more legislative headaches for the private sector with import policy changes – bringing about knock-on effects to supplier nations.

And the country is poised to break new scientific ground: “India has already showcased its capability with missions like the Chandrayaan-series, Mars Orbiter Mission, AstroSat, Aditya-L1, and the upcoming XPoSat, indicating prowess in complex interplanetary exploration. With a rich legacy in space science, I expect India to play a pivotal role in integrating AI, machine learning, and disruptive technologies into space exploration,” says Pratim Das.

The global space hierarchy is already in flux; in the first quarter of 2023, Europe surpassed the US in space tech private investments for the first time, according to a review by Seraphim Space Index. But a disruption of international astropolitics, where focus is shifted away from the US, Europe, China and Russia, and towards the goals and ambitions of newer space nations, will have even greater earthbound implications.

India’s crop of new full-stack Space-Tech companies is pushing growth in adjacent markets. There is a growing global demand for India’s services in geospatial data, for example, whose uses include urban planning, disaster management, and anticipating or responding to extreme climate events.

And, where space technology intertwines with that of national security, India’s growing influence is likely to translate into geopolitical power. The country already has security dialogues with the US, UAE, UK, Australia, France, Chile, and Israel – and these are ripe for expansion.

India has undoubtedly changed the playing field, and the West’s media response to the Chandrayaan-3 mission this August, compared with its coverage of Rohini in 1980, is telling. In a post on X, NASA administrator Bill Nelson wrote “Congratulations ISRO on your successful Chandrayaan-3 lunar South Pole landing! We’re glad to be your partner on this mission!”

European Space Agency (ESA) Director General Josef Aschbacher chimed in with “Incredible! Congratulations to ISRO, Chandrayaan-3, and to all the people of India!! What a way to demonstrate new technologies AND achieve India’s first soft landing on another celestial body. Well done, I am thoroughly impressed.”

Meanwhile, India’s domestic narrative is unchanged. “It has always been one of scientific achievement, national pride and inspiration for the younger generation,” says Phadnis. “ISRO has always attracted media attention. The soft landing on the Moon had unprecedented coverage, with the entire nation glued on to the event. And there were more than 8 million concurrent views of the live streaming on ISRO’s official YouTube channel.”

In which directions will India’s success go? If history has taught us anything, it’s to look to Earth first. “The potential of the space technology for applications of national development is enormous,” writes the ISRO on its website.

Certainly, the country’s superior satellite-launch infrastructure is likely to see it become even more of a telecommunications heavyweight. Then, as space-based communication becomes a primary mechanism to narrow the digital divide, India may hold the keys to a fully connected world. Unlimited internet for everyone? That would really test the world’s power structure.

But perhaps India’s most radical act in the global space ecosystem is not innovation, but imagination. Speaking immediately after Chandrayaan-3’s successful landing, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said: “this success belongs to all of humanity. All countries, including those from the global south, are capable of capturing success. We can all aspire to the Moon and beyond.”

Stay up-to-date with the latest issue of FARSIGHT

Become a Futures Member