In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

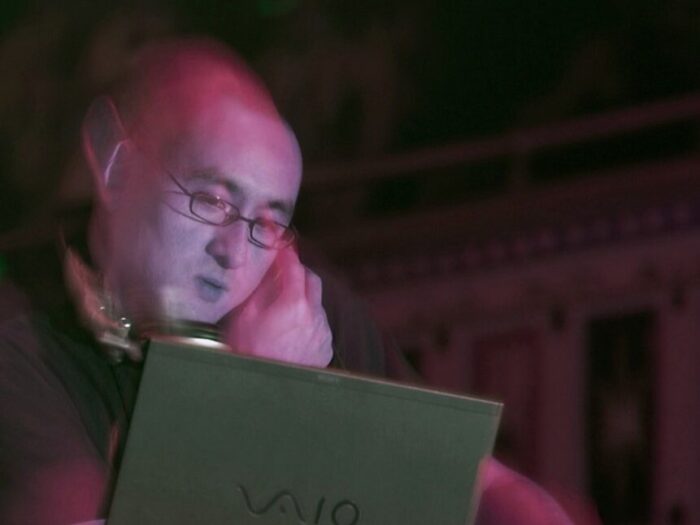

Richard Devine didn’t imagine his career would take such an unexpected turn. One of the Atlanta-based musician and producer’s more recent jobs was to work out just how an LG TV should sound – and that’s just as it’s switched on.

Nor is this the only product he’s worked on. He’s created sounds for products from Barnes & Noble, BMW, Target, Audi, Coca-Cola, and Absolut. More fittingly, he’s worked with instruments from Yamaha and Korg, which are the kind he usually makes music on. One can call Devine a new generation of sound designer, ‘2.0’ compared with the ‘1.0’ that’s long made sounds for stage, screen, or the games console industry.

“Although sound has long been an after-thought to most companies – something they considered only after every other aspect of the product had been decided – they’re now having to think more and more seriously about their sonic signature since so many products have some kind of electric component now”, explains Devine.

‘‘There’s a technological shift with the things we use daily, because now everything is a device. I mean, I control my dishwasher, even my light bulbs, using an app…’’

Consequently, Devine has become the go-to creative to ponder what sort of bleep, blip, whoop, or ding these devices should make. He’ll often sound out his ideas vocally first – he’s a good mimic of electronic sounds – or shape them out by playing on a keyboard before altering the timbre or pitch for different effects. Using his experience as a musician, this process is part art and increasingly part science too, as our understanding of how we interact with and respond to sound grows.

“This is about using sound at a psychological level – you’re trying to create some kind of emotion with these short blips and bloops, because that enhances the experience of using a product. At the same time, you’re ensuring they also work functionally so they articulate the state of the device or system in use,” he explains.

That, he suggests, is harder than it might seem. The sounds have to be simple, but they also have to work within the parameters of the product and the limitations of their speakers – which is a much smaller frequency range than Devine would consider for his music. They have to work across cultural and age boundaries as well as win the product user’s attention without being distracting. And they can’t be irritating either.

“You have to remember that some people will hear these sounds maybe hundreds of times a day, so you have to ensure various sounds work together tonally as a family with- out making people want to kill themselves”, he laughs. “You can spend months trying to come up with the right sound.”

As companies wise up to the need for their products to make sound, there’s a new dimension coming to the fore: the desire to have the right sounds developed for their brand. Devine cites his work for Google, who didn’t want anything edgy or overly complex but rather clean, rounded, simple sounds that they believed echoed Google’s brand values. Audi has even developed a library of sounds deemed appropriate to its various models.

If that all sounds like a stretch, Devine suggests that certain sounds have become intimately, if unconsciously, associated with certain brands – like the ‘bubbly’ sounds that make up the sonic signature of Skype or Nintendo. He argues that McDonald’s and Intel are other examples of how a sonic identity can come to be associated with a certain brand. The sounds a range of products make – their ‘sonic logo’ – can also evoke certain feelings about a brand.

That was certainly Jaguar’s contention. When the carmaker was developing its I-Pace electric vehicle, EU legislation required that its otherwise almost silent engine made some kind of noise at low speed to warn pedestrians of the car’s presence. It had to be a sound that didn’t produce too much sound pollution – imagine the streets full of thousands of EVs all making different warning sounds – but also get the pedestrian’s attention. Moreover, it had to work with ambient sound in various urban environments, as well as wind and rain noise.

“The fact is that Jaguar has a fair history of making great sounding cars and tuning the engine sound to match the product”, adds Iain Suffield, noise technical specialist for Jaguar. “The trick is creating sounds that feel natural and authentic to the EV model in question, while not going so far that you break the illusion or create a sound that ages badly or becomes passé”.

Devine’s solution? A harmonic blend of Jaguar’s conventional engine ‘purr’ mixed with something akin to the pod racers from Star Wars and the light bikes from Tron. After all, if an EV is meant to herald the future of personal transport, why not make it sound somewhat futuristic? Such are the considerations of most EV makers now, as they ponder having to replace a signature combustion engine sound with an artificial one that helps driver feedback and potentially improve the driver experience, at least for those who don’t want to drive in silence.

Devine has since also worked on this conundrum for the likes of Porsche and new EV supercar company Lucid. “Likewise, you can see that the sound scheme of a product will eventually be part of the reason why we buy it over a competitor’s, because we all know how sound can affect us,” he says. “Sound will be considered as much a part of the product’s appeal as its look and function.”

Indeed, he only looks to be increasingly in demand for his ability (and willingness) to, for example, go out into the wild with 200 ambisonic microphones to devise a world of sound environments for Google Earth. This is, not least, because technology is expanding our sonic world rapidly. What was once professional standard equipment, such as VR headsets, is entering the consumer space at breakneck pace. For example, spacialised audio which creates a more immersive sound experience following a 360 degree video, is already available in the latest generation Apple AirPods. Devine should know; not long ago he was appointed Apple’s senior content producer. He’s now its sound guy.

‘‘You can see that the sound scheme of a product will eventually be part of the reason why we buy it over a competitor’s, because we all know how sound can affect us. Sound will be considered as much a part of the product’s appeal as its look and function.’’

“Changes in tech are going to stretch how we experience sounds while gradually moving us towards a more intelligent understanding of how the products we use sound” says Devine, turning once again to his keyboard.

This article was published in SCENARIO Digest issue #8, September 2021. Become a member of the Institute to read the full issue.