In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Representing Unborn Generations

An interview with Sophie Howe, outgoing

Future Generations Commissioner for Wales

Illustration: Lovisa Volmarsson

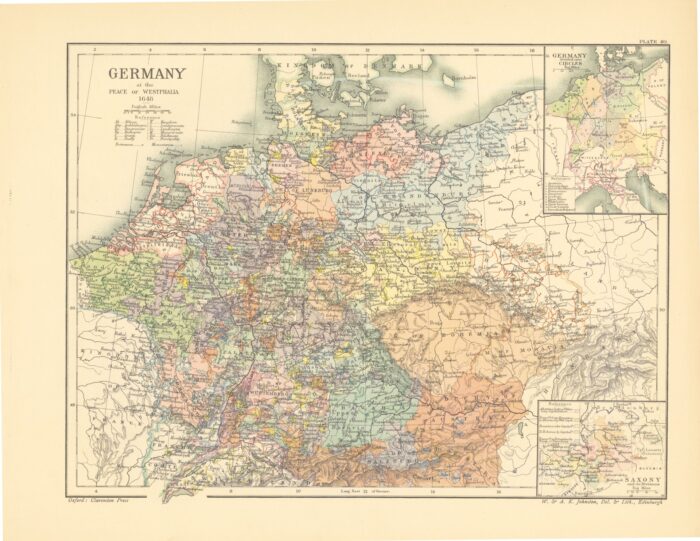

In 2015, the Welsh government took measures against the shifting priorities, hollow reporting, and systemic inertia which often come with short-term election cycles. With the passing of the Well-being of Future Generations Act, public bodies in Wales were required to begin considering the long-term impact of their decisions. Sophie Howe, whose political career started in 1999 when she became the youngest elected councillor in Wales, was appointed as the world’s first Future Generations Commissioner. For the last seven years, she has taken on the role of watchdog on behalf of her constituents: the future citizens of Wales.

“In quite simple, yet mind-blowing ways, this role speaks on behalf of and represents the yet unborn,” Howe explains. “In practice, acting on behalf of future generations involves reviewing the progress of all public bodies in Wales, from local authorities to national institutions, as well as the government itself, to assess if the requirements of the Well-being of Future Generations Act are reflected in their work.”

The Act itself rests on seven well-being goals defined by the Commissioner: prosperity within our planetary boundaries, resilient ecosystems, equality, physical and mental well-being, community cohesion, vibrant culture and language, and taking global responsibility. “The role of Commissioner includes providing support on the steps that should be taken by public institutions to be in alignment with the Act. If they aren’t taking those steps, then it’s the Commissioner’s job to call them out publicly to make sure it happens,” Howe says.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberServing the needs of people who cannot vote because they have not yet been born is all but straightforward. It requires making assumptions in the present as to what the wishes and needs of future citizens might be.

“Naturally, we cannot know what exactly their interests will be,” she says. “So, instead of guessing, we work with the citizens alive today to get their perspectives on the future, what they find important, and what they think is relevant for future generations. This has resulted in the formulation of our seven farsighted well-being goals, which have statutory definitions attached to them. In this way, the seven goals act as a set of principles, by which Wales now judges the progress towards building the society it wants to live in now, and in the future,” Howe says.

When asked to reflect on which political achievements have been made possible during her tenure as Commissioner, one thing stands out to Howe. When she became familiar with proposals to spend the entirety of the Welsh Government borrowing capacity on building a 30-mile stretch of highway to deal with congestion problems, she saw a need to intervene:

“I asked the government to explain how it was in line with the Future Generations Act – which they couldn’t. The business community desperately emphasised all the modelling of the economic benefits that this would bring. I challenged this as well, as it’s neither a solution fit for the 21st-century nor one that is in line with our well-being goals. I was not popular for a long time afterwards,” she says.

“This was an overarching piece that initially wasn’t welcomed and was widely considered a load of nonsense. But we then saw some of the budgets channelled toward bettering public transportation instead, and how it led to a moratorium of more than 50 infrastructure projects. We also increased investment in citizens’ active travel and evidence now shows that the people of Wales are proud of it, to the extent that even the sceptics have been knocking on my door since to say that they appreciate governing toward a long-term vision.”

The statutory power of the Commissioner means that the recommendations of the officeholder carry more weight than those of other kinds of pressure groups or think tanks. Welsh legislation requires that public institutions must cooperate with the Commissioner towards achieving its goals, which are collected every five years in the Future Generations Report. The report is published a year ahead of parliamentary elections and is designed to influence the policies of the political parties.

“In 2021, 64% of the Commissioner’s recommendations were featured in the party manifestos and now 59%, are featured in the program of the Welsh Government,” Howe remarks. Although she considers this a success in itself, there is of course always more work to do, she explains. If given the chance to continue her work, Howe says, her priorities would include pushing harder for more preventative healthcare and to update curricula to include futures thinking in schools.

Present bias is the human tendency to favour immediate payoffs over longterm benefits. It’s an inclination that plagues us both on an individual level and, on a greater scale, in national politics. Here, a narrow focus on the goals achievable within the timeframes defined by election cycles can serve to reinforce and perpetuate problems of the past. It would be hard to disagree with the notion that policymakers should steer with the long-term in mind, but this is easier said than done. Howe highlights this as the most significant challenge related to the Commissioner’s role:

“People’s minds are drawn to the hereand- now rather than to what the longterm effects of our decisions are. I constantly have to pull people into a different mindset that also considers what all the work we are doing today means for the future,” she says.

This task has only become more difficult in recent years, Howe explains, as a state of permanent crisis seems to have become the new normal. She points to Covid-19, the war in Ukraine, heightened inequality, the rising cost of living, as well as issues relating to race, health, and poverty as having collectively contributed to making it more difficult to keep the long term in mind when making decisions today.

“I empathise with public institutions as it’s difficult to find the needed breathing space and mental capacity to look ahead, let alone the actual skills and resources needed to shift from just responding to getting in front of a given crisis,” she says.

“What I think is interesting about the Welsh approach is that it counters a lot of the dystopian narratives about the future by setting out aspirational long-term goals. Governments should continue to do their risk calculations, which remain hypothetical, as no one knows what will happen anyway. But perhaps it’s easier to conceive the path ahead if it steers toward a vision of what kind of country we wish to leave behind,” she says.

“In Wales, we now know where we’re going. You wouldn’t think this would be a special thing, but it’s actually completely unique. No other country in the world has a long-term vision set out in its legislation the way Wales does. The risk of not having such a vision is that it can lead to ineffective political commitments that change from one government to the next – and that’s the problem we are addressing here.”

As part of Wales’ efforts to provide representation for future citizens, the country has established an elected Youth Parliament, from which the Children’s Commissioner and the Commissioner for Future Generations take in inspiration, aspirations, and priorities.

“Wales has lowered the voting age to 16 as a step in the direction of securing youth a seat at the table,” Howe explains. During her tenure as Commissioner, she initiated a Future Leaders Academy with members aged between 18 and 30 who go through intensive ‘reverse mentorship’ programmes designed to prepare them for future leadership roles.

“We pair these future leaders with 50 executives from our public institutions, including the head of the Welsh Government, the Chief Executive of our football association, leaders from our health institutions, and of our Environmental Agency. There’s something powerful to this model,” she says.

“These executives will likely never experience climate anxiety, they are not digital natives, and they are generally far removed from the lives of young people alive today, let alone those to come. The programme is designed to ensure that the impactful decisions they make are informed by the insights and perspectives of the youth.”

Although Wales represents a first in the successful implementation of anticipatory governance, things are beginning to change in other countries as well, albeit slowly.

“Outside of Wales, there aren’t more than a handful of well-integrated anticipatory governance systems to point to,” Howe explains. “But we can look to Finland, Canada, Gibraltar, Singapore, and perhaps the Emirates for examples of this type of work.”

Others may be on their way, however. This includes the governments of Germany and New Zealand, which have both expressed interest in integrating futures thinking and foresight on a policy level. These are encouraging developments to Howe, although she believes it’s doubtful that bigger countries will be quick to implement legislation as wide-ranging as that of Wales.

Signs of promising change are also seen at the UN level, Howe says, pointing to her work with António Guterres, the UN Secretary-General, on the UN Declaration on Future Generations, which she believes could have a potentially massive trickle-down effect on the 193 UN Member States.

There’s still much work to be done to make governments in-tune with the needs of future generations, Howe says, while paraphrasing a quote from Australian philosopher Toby Ord:

“The world spends more money on buying ice cream than we do on financing futures thinking and foresight. I suppose it’s a bit of a humorous analogy, but it’s true. Most public sector organisations don’t have any futures or foresight capacity. If they do, it’s often insignificant. The most important thing to do now is to begin to cultivate the leadership as well as the technical and practical support necessary to make considerations for the future an integrated part of policy development.”

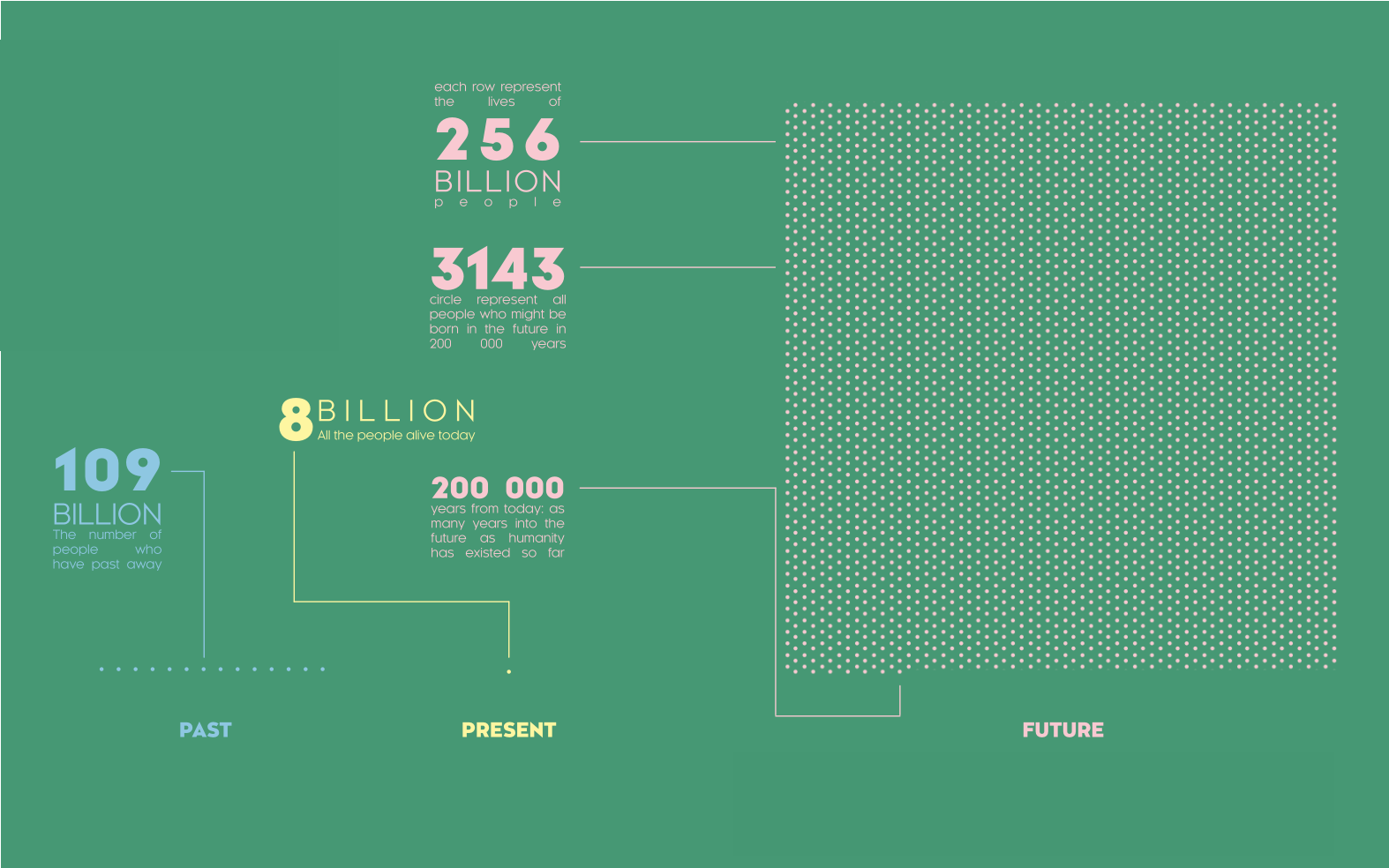

Howe ends our talk on a philosophical note, arguing that the actions we take today should be weighed based on their impacts not only a few generations into the future, but 10s, 100s, or even 1000s.

“In the grand scheme of things, we are currently a tiny existence compared to those 6,75 trillion people expected to be born during the next 50.000 years. The actions we take or do not take today will impact every single one of them,” she says.

Even in this long-term perspective, governments of today have a duty to fulfil:

“I think you’d be hard-pressed to find governments or politicians who will publicly say that we don’t have duties or obligations to the future. And so, my challenge would be, well, if that’s the case, how are you going to demonstrate that? Would you be willing to have someone independent to check whether you’re doing that? And that’s the big test, isn’t it?”

Sophie Howe ended her tenure as Future Generations Commissioner in 2023

This is an article from

FARSIGHT: Safeguarding Tomorrow

Grab a copy here