In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

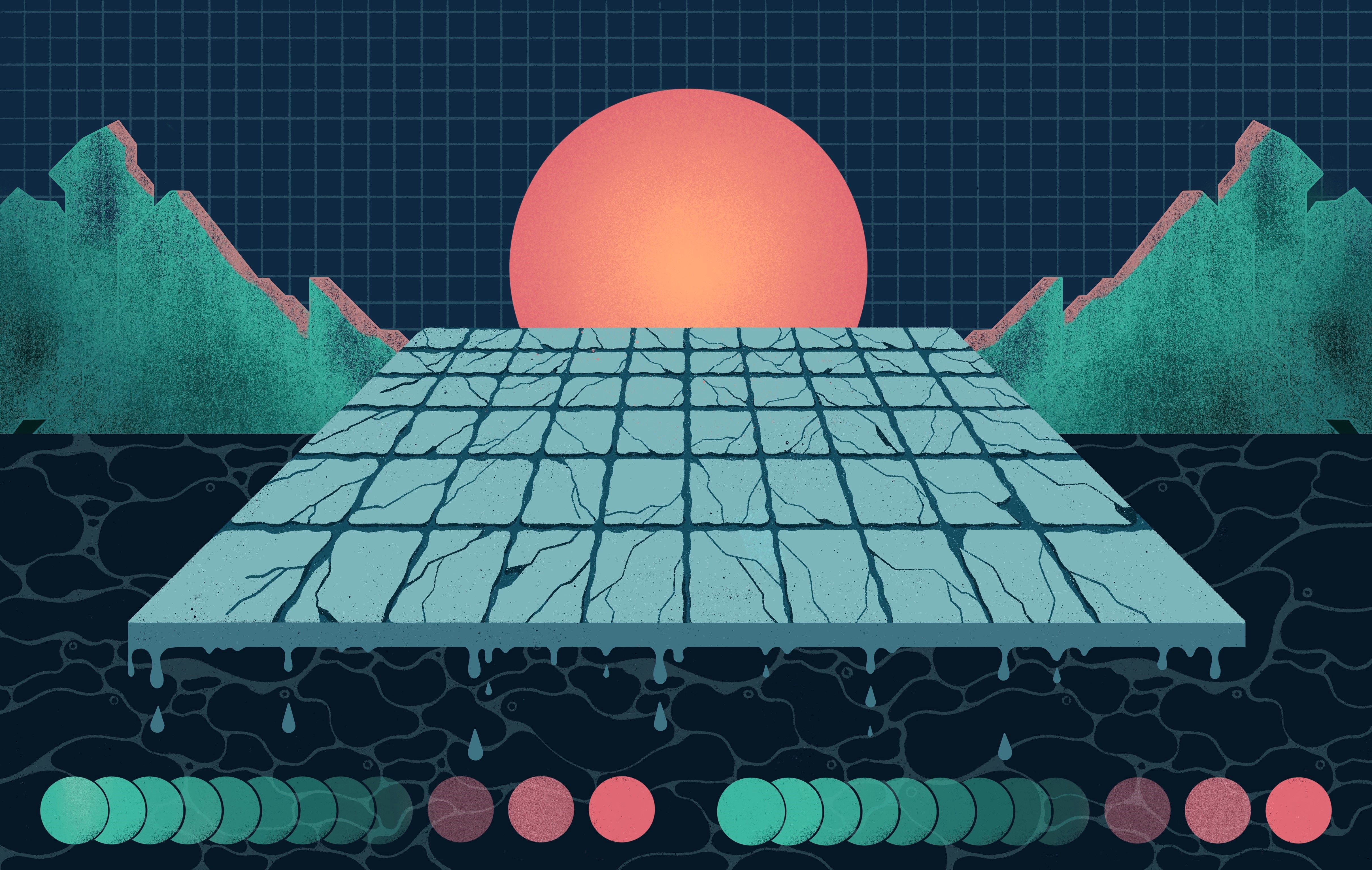

Running Dry

Exploring the global water scarcity crisis

Illustration: Sophia Prieto

Do you have a tap in your kitchen that you can turn on? Go – and watch the source of life flow down your drain. How about a body of water near you? Visit it – and observe its calm flow and gentle waves.

Without water, life on Earth would not exist. It makes up 60% of your body, covers two-thirds of the planet’s surface area, and with 70% of all freshwater consumption going to agriculture, it is the main ingredient in your food. Yet, freshwater supplies worldwide are being drained as a result of climate change, water pollution, and ineffective management of water systems. While scarcity may not threaten life itself, it will make our current way-of-life untenable for our future. Most likely, it will lead to instability, suffering, and conflict as well. Next time you turn on your tap, try to picture the scale of human ravage and capacity for violence possible when the most fundamental building block for our survival becomes threatened.

At first, water scarcity might seem to be an issue concerning numbers: the demand for food is expected to increase by 60% by 2050 alongside an estimated 40% shortfall in water availability by 2030. However, water scarcity is not simply a consequence of there not being enough water volume on the planet. Instead, it’s a by-product of the unequal geographical and economic distribution (and access) to freshwater. There might be enough freshwater in the world as a whole – just not in the places (and at the times) it is needed the most.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberClimate change is one of the most pressing factors affecting water supply, as it impacts the intensity and timing of when water is available, as well as the form it is available in. It matters whether snow or rain hits your field; how distributed the amount of precipitation is; and crucially, when it comes. Unreliable weather patterns create both unreliable water access and water demand. How hot is it out? How thirsty are your crops? Soil fertility also needs to be considered if the soil’s even still there – it may have eroded in last week’s storm.

These issues are exacerbated in agrarian countries, which also tend to be amid economic development and experiencing rapid population growth. In some such countries, agriculture accounts for up to 95% of all freshwater withdrawals.

Pakistan is a useful case-study demonstrating the complex entanglements of climate change and water scarcity. From the foothills of the Himalayas in the north, to the Arabian Sea in the South, Pakistan reveals its maze of mountain ranges, valleys, plateaus, and at the end of the Indu River basin before the river drains into the sea, the Indus River plain. The basin irrigates about 90% of Pakistan’s agricultural production, and with 60% of the population working with livestock or agriculture, as well as 80% of their exports being based on these sectors, the dependence on the basin concerns both food security and economic stability.

Climate change is the most significant factor in Pakistan’s coming water crisis. The Indus River basin is dependent on glaciers in the Hindu Kush and Himalayan mountains which, if lost, can eventually lead to decreased river flow. Currently, these flows are actually expected to remain stable (or even increase) until 2050 due to surges in snow and ice melt runoff amid rising temperatures and unstable weather patterns. In this sense, Pakistan is a great example of how climate change-induced water scarcity isn’t exclusively tied to retreating glaciers and droughts (the total volume of water being scarce), but the timing of peak flow, variability of precipitation, and uncertainty surrounding accessibility.

In a nation such as Pakistan where the population in 2100 is projected to be ten times larger than it was in the mid-20th century, the domestic supply of freshwater will be hard-pressed to meet demand of its agricultural sector. Yet, Pakistan is far from the only nation facing water shortage. As of 2023, 43 countries are listed by the UN as being under ‘water stress’. For these countries, navigating the climate crisis also means navigating water – and food – crises, as well as the other challenges with which they are connected.

While few people die from thirst, many die from contaminated water. Conflict over access to water is also a growing issue. Despite how convenient it would be, freshwater doesn’t tend to obey political borders, and the distribution of freshwater resources has a long history of leading to conflict. Who owns how much of the water in a lake, how much water should someone withdraw from the river before it reaches their downstream neighbour, and where do we go when our groundwater is polluted?

The Water Conflict Chronology is a log of 925 water conflicts since the Babylonian King Hammurabi, collected by the Pacific Institute. Without being exhaustive, the list is telling: water conflicts are nothing new. And not only do they stretch back to the dawn of human civilisation, but they’re also becoming more common as well. Globally, the number of such conflicts has risen sharply since the 1990s – from roughly 16 during that decade to 73 in the past five years alone.

Water can both be a ‘trigger’ of conflict when violence erupts over access and control of water, a ‘weapon’ whereby dams withhold water from downstream neighbours, or itself a ‘target’ during conflict. Furthermore, freshwater is unevenly distributed between nations, and it is often the poorest and most vulnerable that get hit the hardest.

This is also true for how water scarcity interlinks with climate change and increases in extreme weather events. Natural disasters can hit more than one country at once, but different resiliencies, vulnerabilities, and capacities will play a role in the impact of the disaster locally. Some communities are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than others because they lack capacities, such as infrastructure and communication systems, to deal with the resulting stressors.

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereHistorically, the governance of food, energy, and water has often been managed within political and sectoral silos. Water and energy systems have been set up as if the other would always remain both cheap and abundant, and food systems have been built in a way that assumes that neither water nor energy become so scarce that production is constrained. For the thermal power industry, for example, a reliable supply of water is essential to keep energy production and prices steady. This has consequences for industrial food production which, combined with the effects of changing weather patterns on agriculture, can rupture an entire food system. With water, food, and energy systems becoming increasingly intertwined in the future, a need to rethink their governance becomes apparent.

Some steps have already been taken towards this goal. For instance, organisations such as The World Water Vision and the Framework for Action have put forward a model for a holistic approach to governance that links together socioeconomic development with environmental protection.

Although a future of acute water shortage may not be an immediate prospect for most people in the world, the many risks stemming from scarcity means that most parts of the world can expect to be impacted by the consequences in one way or another. As issues relating to water scarcity are amplified, efforts to better govern one of our most precious resources will need to be ramped up as well – and preferably ahead of the looming crises.

This is an article from our latest issue of FARSIGHT: Food Futures

Grab a copy here