In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

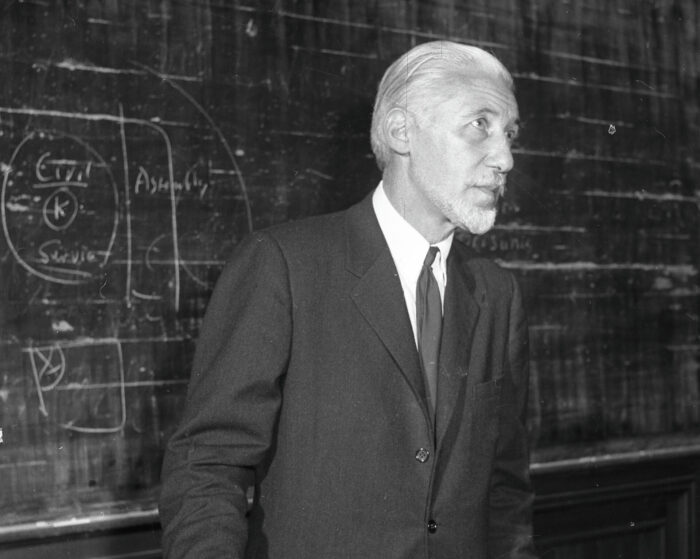

In the second half of the twentieth century, microchips quietly became as vital to global stability and human progress as oil. To better understand Europe’s future role in the semiconductor industry, we speak to Chris Miller, author of Chip War, for his insights.

Illustration: Sophia Prieto

In the second half of the twentieth century, microchips quietly became as vital to global stability and human progress as oil. Chips are geopolitically insecure, require complex technical expertise to manufacture, and rely on some of the most advanced and tenuous supply chains in the world. To better understand Europe’s future role in the semiconductor industry, FARSIGHT spoke to Chris Miller, author of Chip War, for his insights.

Over the course of 2021, as the world’s economy and its supply chains convulsed between pandemic-induced disruptions, people around the world began to understand just how much their lives, and often their livelihoods, depended on semiconductors.”

So writes Chris Miller in the closing chapters of Chip War, a landmark 2022 book that lays out the entire material and geopolitical history of the semiconductor industry. Throughout 2021, two interlinked ‘chip chokes’ were observed: one triggered by sanctions and regulations the US had begun imposing on China, and another from the sheer increased demand the pandemic induced for every conceivable digital product as our lives collectively went online. Data centres, car companies, and every form of electronic manufacturer that required microchips – that is to say, basically all of them – suddenly found themselves in extreme need of more. For several months, the world faced an acute shortage of both simple and advanced microchips.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberThe shortage produced a few economic shockwaves: for automobile manufacturers alone, a market revenue roughly equal to $210 billion was wiped out. A spooked Biden administration ordered an inquiry into the cause of the chip chokes and an assessment of the relative strength of the supply chain. What followed was the US CHIPS And Science Act in August 2022, promising the allocation of $52.7 billion in funding to protect and develop domestic chip production. Perhaps if they had had a crystal ball, they would have seen that with the first release of Chat- GPT in November 2022, the party for advanced chips was just getting started. Miller says that the chatbot’s release has been the single biggest phenomenon pushing the envelope on the semiconductor industry since Chip War’s publication, alongside “the ensuing AI investment boom, which has transformed the chip industry.”

What about Europe? The corresponding EU-led European Chips Act was in fact proposed even earlier – February 2022 – but was not formally adopted by the European Parliament until April 2023. The EU Chips Act pledged over €43 billion to strengthen Europe’s semiconductor ecosystem. Currently, to put it mildly, the wider global semiconductor system hangs in an extremely fine geopolitical and technological balance. Europe has a single, essential entity in the form of the Netherlands-based company ASML. As the world’s only producer of EUV (extreme ultraviolet lithography) machines, ASML currently owns the only technology capable of printing the most advanced chips holding up the world’s digital architecture today, as well as the chips making the AI boom possible. But in 2021, even ASML’s own machinery production line was hit by chip shortages. You need chips to make the machines that print chips. In this sense, the industry has become somewhat of an ouroboros, and a potential ticking timebomb of economic catastrophe – and the world’s governments are growing increasingly anxious.

At the moment, much of the concern surrounding global chip manufacturing chains concerns a scenario in which China decides to annex Taiwan. The contested island nation is home to TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company), which operates the world’s only advanced chip fabs (chip fabrication facilities). These incredibly complex plants are where silicon wafers are printed onto chips with ASML’s EUV machines, using chip designs created by companies like Nvidia and Apple. As Miller’s book argues, if Taiwan’s fabs were compromised, the world would produce 37% less total computing power the next year. This is a percentage that has only increased since 2022, and given that it will only increase further, the aim of sweeping policy like the EU Chips Act is to claw back even a small corner of stability, should more chip chokes come.

“My sense,” Miller argues “is that Europe wants, first, to guarantee more resilience in its key manufacturing supply chains and, second, to ensure that Europe retains a significant role in the chip innovation ecosystem. I worry that, for the latter goal, Europe is playing a smaller role in the AI revolution than it could, which risks also missing the ways that AI will change the chip industry.”

While longstanding issues with European tech talent escaping to America can potentially be solved with the loosening of regulations, incentives and changes in bureaucracy, maintaining a presence in the semiconductor industry requires economies of scale on a far vaster margin than a mere €43 billion.

“The key lesson of both Taiwan and South Korea’s chip industries is that economies of scale are critical for commercially viable production. That’s why companies like TSMC have been so successful. That’s a warning for other countries (including Europe and the US) that want to replicate advanced chip capabilities. It only makes economic sense if the scale is large.” In short, ASML and a small handful of companies operating at various points in the chip supply chain, will not cut it alone.

The outcome of the US’ CHIPS Act has so far been mixed, but with a strong forward trajectory – partnerships with TSMC to build fabs in, for example, Arizona have attracted over $450 billion in private investments across the country, but lacked the skilled labour force that only Taiwan’s decades of experience can produce. The only reason Taiwan has such specialised capabilities in the first place is due to outsourcing of fab labour on a vast scale (a familiar tale told across many manufacturing industries) and the departure of a few key American players in the twentieth century.

It’s a story that’s mirrored across many industries in China, but the prevailing sentiment in American companies like Intel is that the sheer importance and vulnerabilities of semiconductor manufacturing were realised too little, too late. As Pat Gelsinger (CEO of Intel from 2021 until 2024) once said, “God decided where the oil reserves are, but we get to decide where the fabs are.”

While some aspects of both American and European chip-building initiatives have involved cross-Atlantic collaboration and investments, Europe is still very much on its own with regards to strengthening its defences against external forces. “Companies and governments need to ensure they have the resilience their industrial bases need. In some cases, this could involve building more chip production capacity, though I think we must be strategic about this.” Miller argues. “In terms of creating economic value, Europe’s specialized capabilities in lithography, materials, and specialized chips is worth focusing on.” Currently, the EU Chips Act is linked to the Horizon Europe fund for innovation and research, and the Digital Europe fund, which focuses on bringing digitalisation and infrastructure to businesses, citizens and public administration.

Miller is one of a growing number of observers of chip policy who think that current initiatives, both in the EU and the US, are simply not sufficient for the sheer scale the industry demands. For example, while the EU Chips Act aims to incentivise investment and equally to widen access for innovators to that investment, Miller thinks that it doesn’t lead to the sweeping change needed for ensuring that Europe has the research and startup ecosystem needed to build new firms. “Right now, Europe has very capable researchers, but the rest of the ecosystem needed to foster new firms is lacking.”

Taiwan currently represents the greatest bottleneck, both financially and geopolitically. “If the world becomes even more reliant on low-end chips made in China, and high-end chips made in Taiwan, the geopolitical vulnerabilities are obvious. But if the chip industry diversifies, with Japan, Korea, Singapore, the US and others playing a role, then Europe might still be able to access the chips it needs,” Miller says.

At the moment, outside of Taiwan, only South Korea can be said to be a major player in the manufacturing process of the most advanced chips (think those designed by Nvidia) which are currently being bought in gigantic quantities by American and Chinese firms trying to train and maintain AI models. China, which has historically been both artificially and organically limited in its ability to design and manufacture chips, is a mere 160 km from the so-called ‘Silicon Isle’ of Taiwan, and the apparent value of controlling TSMC grows with each passing year.

A recent example of the uncertainty concerning semiconductor governance and policy is the macroeconomic chaos caused by the Trump administration’s tariffs on not only China, but the sale of chips themselves. Trump’s “mix of threats and dealmaking” (Miller) has already put major roadblocks on American attempts to attain a kind of self-sufficiency and the reversal of many decades of offshoring.

What has worked in the past will no longer work in the future; the semiconductor industry is too reliant on globalised systems for any single country to capitulate. China needs the US, the US needs Europe, Europe needs Asia, Asia needs China… and on and on it goes. It is becoming increasingly clear that pursuing aggressive policy with regards to sovereignty, or foreign sanctioning, will only cut one head off the basilisk.

I ask Miller if it’s possible that a revival of domestic chip sovereignty and manufacturing could be instigated by the military-industrial complex – it’s what drove many of the greatest leaps forward in chipmaking during the Cold War. Trump’s scepticism of NATO is leading to huge surges in EU defence manufacturing investments, and the fact that Taiwanese chips are indispensable in basically all modern weapons systems, could make the scenario more pressing.

Miller reiterates that the past is not a guide to the future: “For the foreseeable future [Europe’s] defence industry will be closely intertwined with the US defence industry for key electronics. That’s just the reality of how supply chains work. It will take a decade of investment, plus a common European strategy, to build more autonomous supply chains.”

For its entire history, chip production has followed Moore’s Law, proposed in 1965 by Gordon Moore, who would later go on to found Intel. Moore proposed that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit (chip) doubles approximately every two years, and his law has remained unbroken ever since. Radical new chip architectures have been proposed since we are nearing the horizon of what is even physically possible – ASML’s EUV lithography, for example, generates a wavelength of 13.5 nanometres to print silicon, and we simply can’t go much smaller. Quantum chips, photonics, and new materials and architectures may be a narrow route for Europe to pursue (“Hard to predict!” says Miller), but in the meantime, the EU and the rest of the world’s global tech powers are inseparably bound to one another.

This article was first published in Issue 14: European Futures