In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

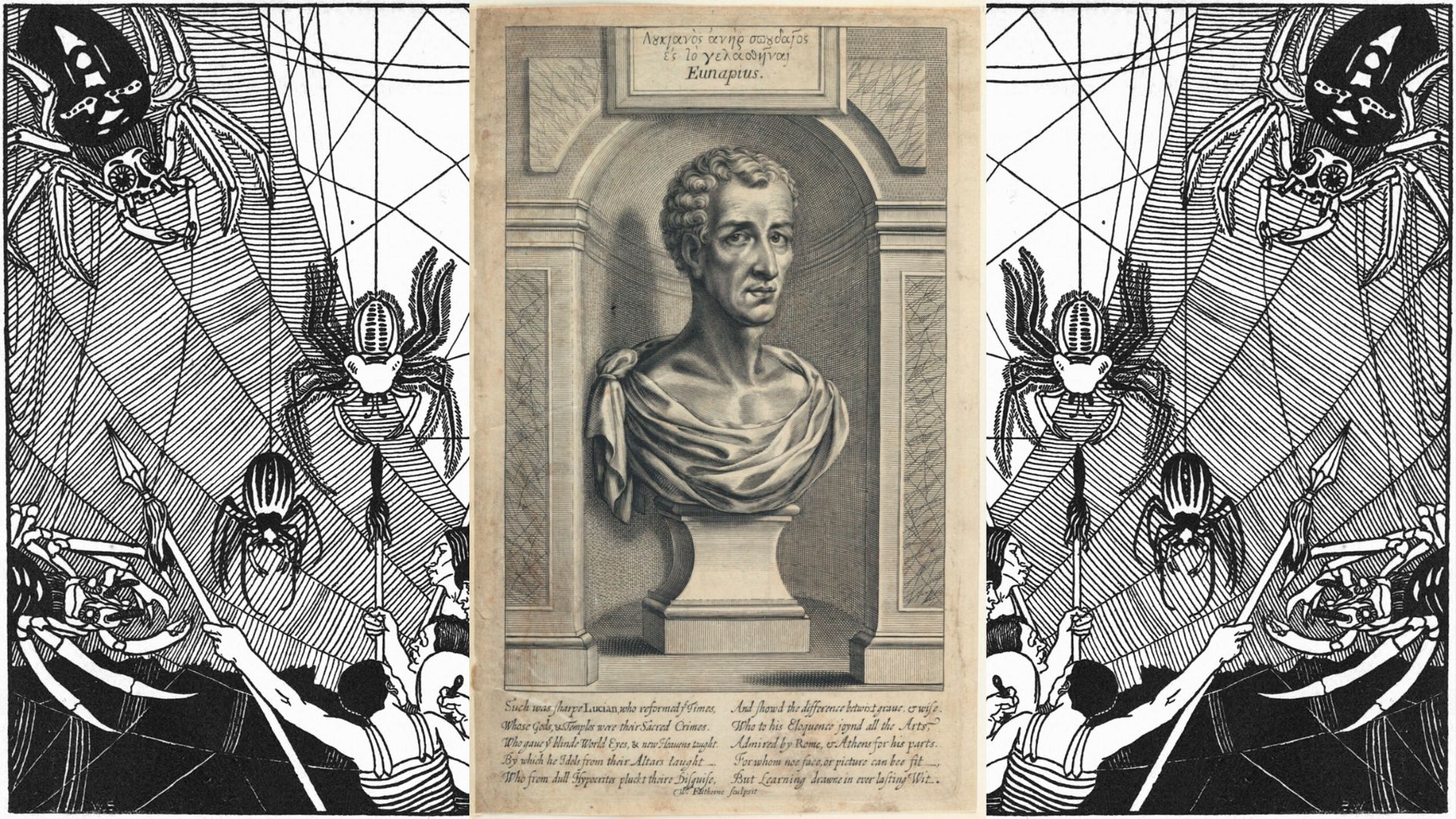

The Ancient Assyrian Who Invented Sci-Fi

Before Thomas More or H.G Wells came the

tongue-in-cheek satirist, Lucien of Samotasa

Throughout most of human history, technological change was an extremely slow and gradual affair. Humans were born, lived out their lives, and died without seeing significant material change to their surroundings or any significant social change to their community or society. Our earliest known technologies, stone tools, were in use for millions of years with very little alteration to their design until approximately 200,000 years ago, when the pace of innovation began to pick up and new innovations began to emerge and disseminate throughout the populated world. Of course back then, technological change was maddeningly slow by today’s standards.

It wasn’t until the industrial revolution that things really kicked off. Technological development began to accelerate at a breakneck pace, and the social and political repercussions of this new pace of change were felt globally. The experience of fluid and rapid change provoked thinkers and artists to conceive of worlds to come that were radically different from their present, simply because constant flux had become a condition of life. ‘The future’ was invented, populated and colonised, and it became a source of hopes and fears. Most of all, the future became a domain of fantastical opportunity and promise supplied by the experts, technicians, inventors, and scientists of a new age. For many people who were alive at that time, it seemed that humans had, or soon would have, the power to will anything into being through sheer ingenuity. Science fiction emerged as a literary genre that attempted to push the boundaries for what was possible and imagined radically different worlds, often as a vehicle to push for change in the present. Early science fiction was spearheaded by the likes of H. G. Wells, who believed that fiction could be a powerful productive force that could help us steer the world in a more peaceful and harmonious direction by warning of all the things that could go wrong if we didn’t.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberSo the story goes. And it’s a story that makes sense in a lot of ways. Science fiction is a genre that seems closely tied to the new reality of endlessly accelerating technological and societal change that arose during the industrial revolution, and which has persisted to our present day. You need to have experienced radical technological and societal shifts in your lifetime to imagine more shifts to come in the future. So, naturally, the ancients didn’t invent science fiction – the Victorians did.

It’s a neat historical narrative, but on closer inspection, perhaps a little too neat. Consider the fact that an ancient Assyrian named Lucian of Samosata wrote a tale containing some of the most common tropes of sci-fi (first encounters with alien lifeforms, interplanetary warfare and space colonisation) more than 1,700 years before H.G. Wells published War of the Worlds.

A brief summary of Lucian’s A True Story goes as follows: During an ocean voyage, the author and his companions find themselves and their ship sucked into outer space by a tornado. The crew sail on, thinking they are still on Earth, until they eventually arrive at the Moon and find it inhabited by an alien race, the Moonites. War has erupted in the galaxy, and the Moonites are locked in a deadly conflict with the inhabitants of the Sun, the Sunites, battling for control over outer space colonies. The travellers join the Moonites in their struggle against the forces of the Sun and witness fierce battles between the celestial kingdoms, which include cavalry charges by enormous winged centaurs, warriors riding oversized gnats, giant spiders spinning webs through space, and a number of other fantastical phenomena. Eventually, after fierce battles between the Sun and the Moon, a peace treaty is agreed, after which the travellers get a chance to observe the strange lives and customs of the aliens. They find that the Moonites have developed advanced technologies, including sophisticated surveillance tech which they use to spy on Earth. Eventually, the travellers return to their home planet to continue their adventures, which include being swallowed by a giant whale and meeting ancient heroes of Greek mythology.

Needless to say, Lucian doesn’t exactly fit the bracket of a science fiction writer. He didn’t grow up in an industrialising European metropolis; he came from an ancient village on the banks of the Euphrates. The world he inhabited was far removed in time from the rapid pace of scientific discovery and technological invention that characterised the industrial age and the fiction that arose from it. Lucian would have seen very little technological change during his own lifetime, which makes the concepts and ideas he writes about that much more interesting. How do you conceive of spaceflight when your most advanced mode of transportation is a horse?

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereThe most likely answer is that Lucian didn’t see his own fantastical concepts as plausible projections of things to come, but as mere fantasies of the mind. He probably wasn’t as interested in the mechanics of spaceflight as he was in how it could be used as a means to propel his story into new absurd domains. In fact, the means of locomotion through outer space of the travellers in Lucian’s story are much the same as on Earth: a gust of wind carries their ship to the Moon, as it would on the sea. Lucian didn’t think the strange technologies or alien societies he described did or ever would exist; rather, he primarily used these fantastical story devices to poke fun at his forerunners in the ancient literary world, who passed off fantasies, wild exaggerations, myths and legends as truths. True History was a satire, after all, although much of the humour is rooted in references to ancient world authors and concepts that may be lost on most of us today.

Perhaps asking how an ancient Assyrian could invent science fiction is simply the wrong question. What is or isn’t science fiction is a matter of genre boundaries, which is a highly fluid matter, resting on the academic question of where you draw the line between one area and another. Some scholars have even suggested that the oldest known piece of science fiction is not True Story, but the Epic of Gilgamesh, written down in Mesopotamia almost 2,000 years before Lucian’s time, due to its exploration of human nature through fantastical elements. Ultimately, it all depends on how loose your definitions are.

What Lucian’s True History does tell us is that the human capacity for imagining radically different worlds – both present-day and future varieties – is not necessarily something that is as closely tied to context and circumstance as we would like to believe, but is rather universally human.

It makes you wonder whether our ancient ancestors, with their Stone Age tools, told each other stories about alien species and foreign worlds as well.

Read the latest issue of

FARSIGHT:

Tomorrow’s Day Off

Grab a copy here