In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

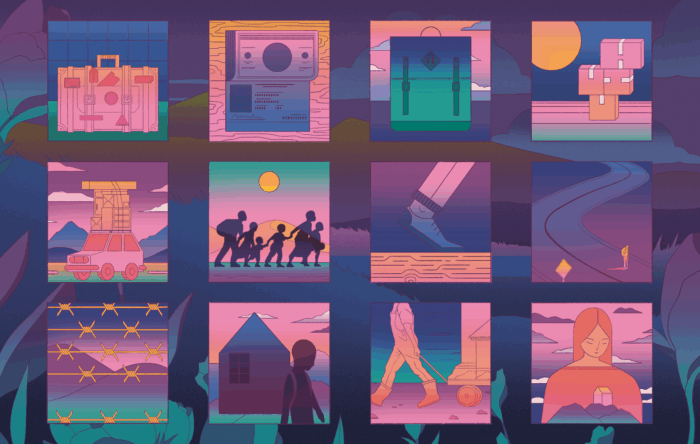

The Cybertariat

A closer look at human-powered automation and the hidden side of the digital economy.

We humans have always sought to use technology to simplify or automate work tasks. Although we’ve come a long way from Stone Age tools to today, where most of the global population carries a powerful micro-computer in their pocket, our striving to do more while working less has been a constant throughout history. With today’s rapid advancements in robotics and artificial intelligence, a future may now be approaching where automated, self-functioning technology has taken human labour out of the equation entirely.

Cars may soon be self-driving, your future digital assistant can proactively take care of your every need, and artificial intelligence can perform an increasing amount of cognitive labour much better than we humans can. Yet although expectations are high for what technology can help us achieve, we haven’t quite arrived at anything resembling a fully automated future yet – and it may in fact be further off than we tend to think.

It’s not that the hype isn’t there, at least not if measured by the massive amounts of funding that AI start-ups tend to attract – on average between 15-50% more than other technology firms. Dig a little deeper, however, and we find that much of the hype surrounding this burgeoning AI industry is unfounded at worst and overblown at best. A survey of 2,830 AI start-ups in the EU revealed that 40% of them were not using AI in any significant way.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberThe illusory grip of AI extends beyond the marketing of tech startups, however. One often overlooked facet of the platform-based economy and the algorithms that power it is that much of it is dependent on precarious and cheap labour to function. This curious phenomenon is what Phil Jones, author of the book Work Without the Worker, has dubbed ‘fauxtomation’ (an amalgamation of ‘fake’ and ‘automation’). The term refers to the fact that novel AI-dependent technologies often market themselves on an illusion of automation, while being entirely dependent on human input. Otherwise known as ‘microworkers’, these digital labourers are an essential cog in the wheel of many of the technologies that power the platform economy. In some cases, they even make up the foundation allowing the business models of these platforms to succeed.

Their work includes ranking Google searches, cleaning data, identifying NSFW (Not Safe For Work) images, supervising algorithms, and performing other chores that require human cognition. Specific tasks could be labelling data in an urban area to show a self-driving car how to navigate a city, or tagging pictures of faces to train a facial recognition algorithm how to recognise a face in a crowd. What’s interesting about these tasks is that most of them, from an end user’s perspective, seem to rely solely on the pattern recognition skills of powerful and complex algorithms. And yet without humans in the loop, they simply wouldn’t function. It’s a sleight of hand which Jeff Bezos has aptly named “artificial artificial intelligence”. Rather than having liberated humans from repetitious, monotonous labour, the new digital platform economy is helping sustain this type of work.

Members of the new class of digital labourers often work as independent contractors, hopping from microtask to microtask, meaning they are not covered by minimum wage laws or other labour protections. They are mostly hired from underprivileged populations in the Global South, with a median earning of $2 per hour.

It might come as a surprise how highly reliant on low-skill human labour the high-tech areas of our economy really are, but the underlying logic is fairly simple: why spend fortunes developing and implementing a piece of software that can perform boring, low-skill work tasks if sufficiently cheap and easily accessible labour exists somewhere in the world that can do so manually? Cost-cutting has always been an incentive for labour-saving technology; remove that incentive and automation becomes unnecessary.

It’s part of a broader story of the ongoing ‘taskification’ of work – the breaking up of jobs into individual tasks that are outsourced to the lowest bidder – no matter where or who they might be. This process didn’t start with the rise of microwork platforms but is in many ways a product of the internet. Already in 2003, Ursula Huws, Professor of Labour and Globalisation at the University of Hertfordshire, coined the term ‘cybertariat’ to describe the new class of workers who make their living on the internet. This ongoing atomisation of the workforce, she recognised, marked a break from the 20th century economic model of stable salaried employment. While the trend is not new, the rise of the platform economy, social media, and the proliferation of smart phones and internet access around the world has exacerbated it.

So, while worries connected with technology and labour often involve highly intelligent machines displacing us, taking our work, or perhaps even enslaving us like in some sort of Terminator fantasy, the more immediate risks come in the form of more conventional threats to worker wellbeing: unsecure, non-transparent, and precarious working conditions, facilitated by the global fluidity of work and tucked away under the shiny hood of digital technology.

One of the more famous platforms operating in this space is Amazon’s crowd-sourcing marketplace ‘Mechanical Turk’. The service takes its name from a purportedly automated (and unbeatable) chess machine that toured Europe in the 18th century – in retrospect a very apt name, considering that the machine was actually run by a chess master who hid inside of a box.

Mechanical Turk offers access to a “global, on-demand, 24×7 workforce” who supply companies with a human labour force that can perform cognitive labour, often the kind that is widely assumed by the end user to be fully automated. Each month, millions of “Human Intelligence Tasks” (HITs) are completed by the platform’s 100k–500k users (referred to as “Turkers”). One in three Turkers are otherwise unemployed and only 4% of all workers on the platform earn more than the United States’ federal minimum wage of $7.25/hour. Nonetheless, the platform has grown in popularity, especially in India, where the pay rates are more favourable. Mechanical Turk is far from the only platform, however. Competitors include Crowdflower, Freelancer.com, and Clickworker, the largest of them all which passed 2 million registered users in 2020.

At surface level, it may seem that microworkers of the cybertariat benefit from the existence of these platforms; after all, they offer them the opportunity to work when they otherwise might not have had any. Yet when viewed in a broader perspective, the case is often that these workers began performing this type of work because technological advancement had replaced their previous employment.

It’s a clear example of what happens when market-driven interests and the interests of workers are too out of balance. When fragmented and isolated from each other – often not even able to communicate with peers on the platforms – workers lose the bargaining power they would otherwise have on the labour market. It’s also not a coincidence that the Global South is where most of these workers are located. Apart from the wages from microwork being more favourable in countries like India, nations in the Global South also tend to be more lax regulatory environments promoting “low rights environments where there are few expectations of political accountability and transparency.” These are some the same reasons why India has in recent years become is a hotspot for training and testing technology by tech giants.

But microwork is not relegated to the Global South – the platforms are available in the Global North too. In cooperation with the start-up ‘Vainu’, prisons in Finland, for example, brandish an initiative whereby inmates can supposedly train their vocational skills by performing Mechanical Turk tasks that would otherwise be outsourced to microworkers. As is common practice with prison labour, the inmates are underpaid, with the governmental overseers of Finnish prisons receiving an undisclosed percentage of the microwork payslip from Amazon. It’s a example of how even in a country claiming one of the most progressive prison systems in the world, the cooperation of the state and capital ignores concerns over exploitation when work is portrayed as ephemeral, simple, and hidden from public view.

New technologies reflect and amplify our pre-existing social relations. While decades of globalisation and widening value-chains have alienated much of the labour gone into the goods we buy today, we can nonetheless recognise that it still exists. Coffee beans need to be picked and trucks must be driven. Microwork, on the other hand, increases the opacity of global labour to a level where companies don’t even acknowledge the existence of the people powering their own platforms. The issue, therefore, is primarily one of accountability. Certainly, technological innovation itself will not solve the issue. On the contrary, as the world becomes increasingly interconnected, spaces for potential exploitation may increase – VR and metaverse-enabled work through a person’s ‘digital-twin’ would allow workers to perform more immersive and kinetic-based tasks remotely, for example. A less bleak future for the cybertariat is possible, but without a greater degree transparency and responsibility, the fate of labour in tomorrow’s hyperconnected cyberspace remains solely in the hands of the platforms that facilitate it.