In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

The Digital Divide

Sub-Saharan Africa is unevenly online, posing problems to the region’s socioeconomic development.

In the highly developed world, there is a tendency to see digital connectivity as a universal feature of modern life. To be a citizen of the world is to be ‘on-the-grid’: either plugged-in to an endless stream of network activity or having one’s personal data exchanged across the globe. Smartphones have re-defined connection in the 21st century to the point where they constitute a virtual extension of our own brains. It’s difficult to imagine a life less online than it is today.

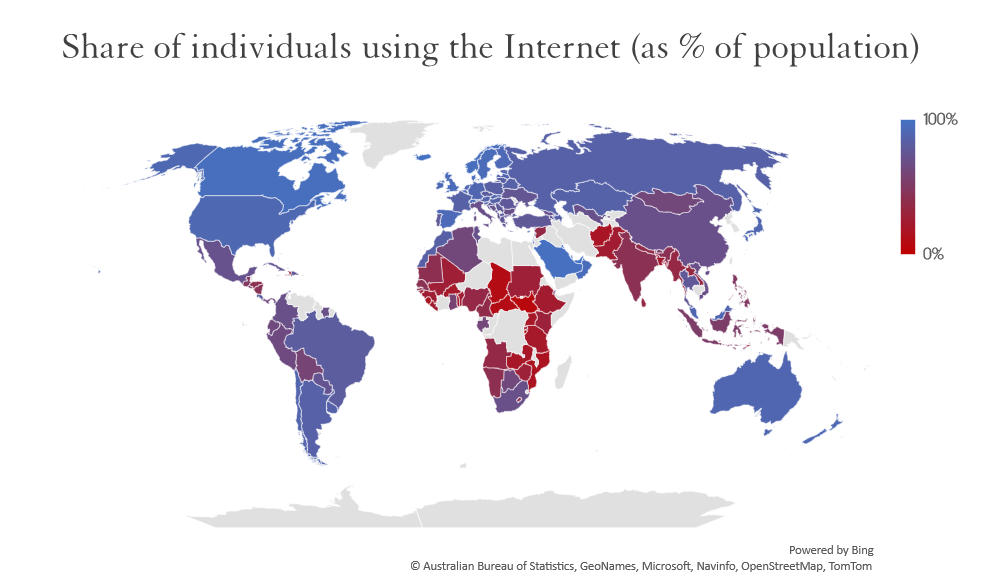

On a global scale, however, such views are myopic. Despite decades of globalisation, internet usage and infrastructure lag significantly behind in many parts of the world. One region especially affected by digital neglect is Sub-Saharan Africa, where 33 out of the 46 least developed countries (LDCs) are located. On average, only 30% of people in the Sub-Saharan region use the internet – exactly half of that for the world (for high income countries the average lies at around 90%). These extreme differences are what some have termed as the Global Digital Divide.

Many would argue that today, access to the internet is a basic human right. Some of the many benefits provided by digitalisation include improved levels of education, health care, government transparency and effectiveness, job creation, and enhanced business opportunities. In a modern context, connectivity provides a structural basis for socioeconomic development.

The first obstacle towards Sub-Saharan connectivity is the lack of an existing digital infrastructure. Even though the global internet’s network of fibre-optic submarine cables reaches every corner of the world, 45% of Africa’s population is further than 10 km away from any fibre network infrastructure, a share larger than on any other continent. This is in addition to a major lack of access to electricity: in total, under half of the region’s population (48%) has access, with South Sudan ranking lowest at 7%. In short, mobile phone proliferation is greater than electricity access. And although progress is being made in electricity access, this might be slowed down, or at worst, even reversed, given the current energy crisis as of December, 2022.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

BECOME A FUTURES MEMBERFor Sub-Saharan Africa to increase its digitalisation capacity, it is important that stakeholders take into account the ‘analogue’ components of digitalisation as well. This can range from creating adequate regulatory frameworks to an education system promoting IT use. Ignoring such initiatives risks widening what some term the digital ‘usage gap’: when internet access doesn’t necessarily translate into the active use of digital technologies. For example, some estimates suggest that almost 53% of the Sub-Saharan population lives in the range of a mobile signal but fail to make use of it, leaving only 28% of the population actively using the internet via mobile networks. Much of the difference between cellular versus broadband usage can be explained by affordability. Cellular broadband is generally cheaper than fixed broadband, so much so that, as of 2020, mobile internet has actually become relatively cheap based on average monthly GDP per capita.

Despite infrastructural hurdles, there are growing signs that positive change is lying ahead. Over the past twenty years, electricity and internet access have been continuously growing in absolute terms, as well as the number of mobile subscriptions. Although this development has not been steeper in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to other parts of the world, it is still moving in the right direction.

In turn, some tech giants see this as a great opportunity for investment. For example, both Google and Facebook have launched projects aiming to increase Africa’s connectivity by building sub-marine cables around the continent’s perimeter. Microsoft, on the other hand, is focusing less on critical infrastructure and more on strengthening the African start-up community. This is being done via setting up a ‘Founders Hub’, which commits towards helping 10,000 start-ups over the next five years by giving them access to technology, markets, funds, and courses. “Start-ups,” in the words of Wael Elkabbany, Managing Director of Microsoft’s Africa Transformation Office, “will provide the foundation for Africa’s digital economy.”

And indeed, multiple tech start-ups have emerged across the continent in recent years. In 2021 alone, for example, four new start-ups have earned unicorn status. Many of these companies operate within the financial tech industry, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. One of the already well-established success stories is the Kenyan start-up ‘M-Pesa’ launched in 2007, which “revolutionised” the virtual banking system in the region. The system works by using SIM cards that allow users to transfer money via SMS. The service is also available offline, facilitating digital integration beyond the borders of cyberspace.

There are also positive developments on the digital literacy front. For instance, in Rwanda, the government has established a Digital Ambassadors Programme aiming to provide digital literacy training in rural areas with a special focus on women and people with special needs. Through further support from the private sector, the programme could potentially create jobs, increase productivity, and widen access to governmental, health, and commercial services.

There are also efforts towards reducing the price of mobile phones that can often cost as much as an average family’s monthly income. For example, Ethiopia has partnered up with Chinese manufacturers to produce cheaper phones by assembling them locally. On a continent-wide level, the mobile telecommunications company, MTN, has also introduced a so-called “low-cost smartphone” for only $20.

Nevertheless, one must keep in mind that it can take many years before digitalisation becomes a core component of Sub-Saharan Africa’s civic infrastructure. Until then, the economic and societal divide of the region needs to be addressed in alternative ways where technologies do not necessarily rely on reliable internet access. In fact, some Sub-Saharan African countries have already introduced new types of solutions to accommodate this need. As an example, the use of drones is making major strides in delivering smaller goods in certain countries, such as Rwanda. Particularly useful and cost-effective in supplying healthcare, drones have revolutionised blood and medical supply delivery in regions where a majority of the population lives in rural areas. Ghana has also followed Rwanda’s footsteps, where during the Covid-19 pandemic, both countries ensured contactless and smooth delivery of such goods, regardless of supply chain disruptions.

As progressive as these solutions may seem, they nonetheless might carry the baggage of what some refer to as ‘digital colonialism’. Many of the technological advancements in the region, such as drone solutions, are developed and introduced by Western companies, where the accumulated capital does not necessarily stay in the country they’re used in. This is especially problematic when considering the ambiguity of investments that ‘only’ focus on improving digitalisation in general terms, rather than improving the connectivity between different geographical and social groups. Investors are often drawn towards digital ‘hot-spots’ with pre-existing interest in digitalisation, and where large sums have already been. Over time, this could lead to a digital divide in Africa internally. What’s important, therefore, is not only that a digital infrastructure is ensured in ‘Africa’ as a blanket decision, but that regulations promoting the effective distribution of these investments are created as well.

With such initiatives, Sub-Saharan Africa could potentially reach intensified and equitable growth in the coming years. A digitally integrated continent. The question is whether the public and private actors can work together effectively to accomplish this goal.

Become a Futures Membership Today

Broaden your horizon about future possibilities and stay updated on key trends and developments through: