In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

The Four-Day Work Week Is Here

We cannot deny that our society is growing increasingly stressed out and unhappy. According to Gallup’s 2022 Global Emotions report, based on nearly 127,000 interviews with adults in 122 countries and areas, global unhappiness has risen over the last decade, with Gallup’s Negative Experience Index rising steadily from 24 in 2011 to an all-time high of 33 in 2021. This growth does not seem particularly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. Fewer people in the survey felt well rested than at any time since 2008, the height of the financial crisis.

Work is a major factor in unhappiness. The American Institute of Stress has found that 94% of American workers feel stress at work, with no fewer than 63% ready to quit their job to avoid work-related stress. In 2021, the World Economic Forum reported that workers’ daily stress reached a record high the previous year. While the pandemic may be responsible for some of this stress, global workplace stress also grew steadily from 2009 to 2019, before the effects of COVID-19 was felt. Even countries that are generally considered happy feel the sting of unhappiness. In Denmark, which tends to be in the very top of happiness indexes, one-third of young women and one-fifth of young men report poor mental health, and more than half of the young women feel stressed.

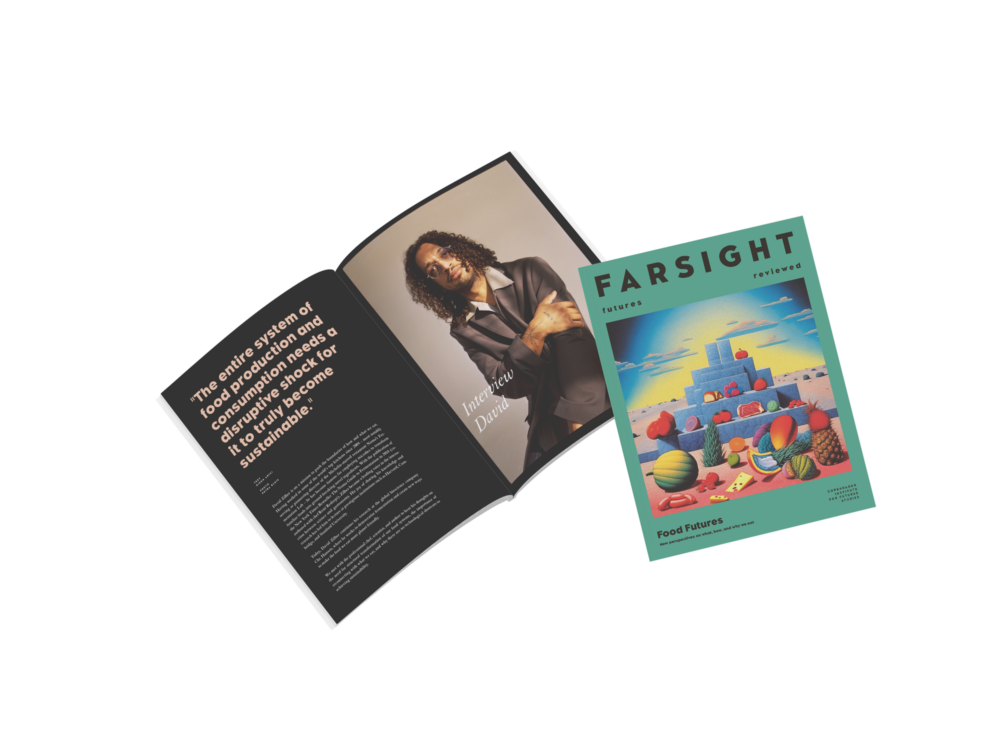

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberOur societies keep growing richer as we measure wealth, but the price for that increasing wealth seems to be growing stress and unhappiness. Maybe it is time to rethink wealth and focus less on increasing material wealth and more on increasing mental health. However, there are ways to increase mental health, especially workplace-related stress, without necessarily reducing material wealth. One of the best documented is to start working four days a week with no reduction in pay.

Choosing to work fewer hours is not a new thing. Since 1870, the average annual hours worked in developed countries have declined from ca. 3,000 hours to ca. 1,600 hours, though the speed of this decline has slowed down in recent decades. It can be argued that as working hours declined, we instead worked harder when at work, as productivity demands increased – which could explain why work-related stress is increasing. Maybe it is time to truly work less rather than just compressing the workload into fewer hours. Studies have shown that working more hours doesn’t increase the amount of work done, with the cut-off before productivity suffers at 30 or 35 hours a week. Hence cutting down work hours doesn’t necessarily mean accomplishing less; in some cases, more work is in fact done when the workday is reduced. As a bonus, workers feel less stressed, more rested and experience fewer negative emotions. For this reason, many companies (and some countries, such as Wales) are testing or considering shorter work weeks without reducing pay.

In 2022, a selection of mainly US and Irish companies underwent a 6-month trial where employees worked 4 days a week – a 20% reduction in work hours – with no corresponding pay reduction. The 27 companies that responded to a trial survey rated the experience 9 out of 10, and none of them planned to return to a regular 5-day schedule. Workers reported lower levels of stress, fatigue, insomnia and burnout, and improvements in physical and mental health. Revenue didn’t suffer, quite the contrary: Average company revenue rose 38% when compared to the same period the previous year. The results of a corresponding, larger UK trial involving 73 companies have yet to be published, but a halfway survey indicated similar results.

Many employees not involved in 4-day work week trials choose to work less even at a cost in income. In Australia, enough people choose to work part time to make the average work week per employer 29 hours. In general, people in high-income countries have the shortest work weeks, indicating that when people can afford to work less, many do.

Even though the above indicates a movement towards a 4-day work week, not everybody is likely to get the opportunity. In many sectors, such as manufacturing, cleaning and retail, productivity is closely connected to work hours, and companies in these sectors will be less willing to reduce the work week for employees without also reducing pay – and many employees in these and other low-income sectors cannot afford a pay cut. Unless a 4-day work week with no pay reduction becomes mandatory by law or collective agreement, it is quite possible that mainly people working in in high-income sectors will get the opportunity to work less, whether at no pay reduction or a voluntary one. The result could very well be greater polarisation between workers, with some working less for more, with improved mental health, while others work more for less, with associated stress and unhappiness. Will the more fortunate feel solidarity with the less fortunate and fight to improve their work conditions? That remains to be seen.