In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

The Future Will Also Be Here Tomorrow

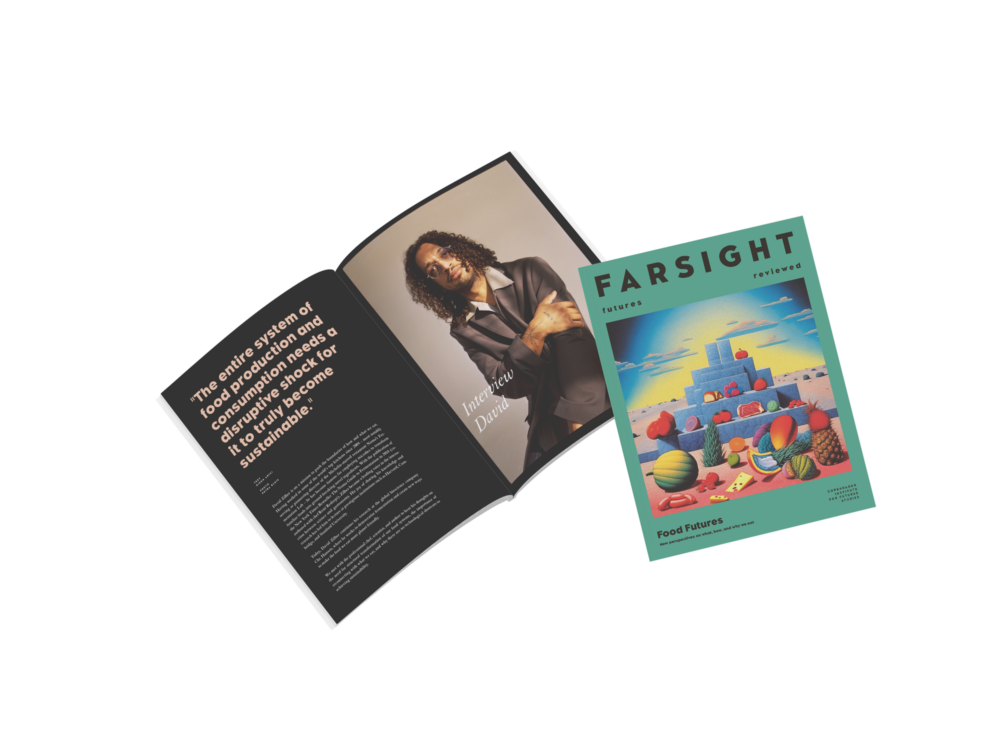

Image credits: Bobby Mandrup & Beowulf Sheehan

Although Kristian Leth describes himself as a storyteller with an aversion to grand narratives, the Danish author’s upcoming book Fremtiden er der også i morgen (The Future Will Also Be Here Tomorrow, April 2023) is nevertheless born out of a desire to give a new sense of purpose and direction to the way we think – and dream – about the future.

Leth, a father of three, wrote the book for young people with the intention of inspiring them to build more hopeful stories for tomorrow which break with the pessimism characteristic of our age.

We met with him for a talk about intergenerational responsibility, the limits of rationality, questioning authority, and the importance of inspiring by example.

Why did you feel the need to write this book?

When my children reached the age where they started asking big and difficult questions about life, the planet, and the future, I had to admit that I didn’t know what to say. As a parent, when your children come to you with questions and fears about the future, you want to have answers ready. I just didn’t.

It was an incredibly difficult period. I was hit by such negativity and pessimism. I live in New York, and I remember driving through the city from Newark Airport to Brooklyn while thinking: all of this, what is it? How is this ever going to work? I was haunted by an overpowering feeling that nothing could possibly make sense.

So, what I started to do was to begin reading and researching in order to build a better understanding of the actual state of the world. I started talking to climate researchers, futurists, historians, and statisticians. What I found out is that the world is better off on a lot of measurable parameters than it has ever been before. Although I am suspicious of big convenient narratives, it was reassuring to discover that my own anxiety and fears were not necessarily reflected in the facts. The question I then had to ask was why so many people feel anxious about the future.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberThis book is not intended to dismantle the prevailing paradigm, or to explain that the world is more complicated than what you might think. But I simply had a feeling that for young people, we almost owe it to them to present some sort of vision. That’s why I wrote the book.

The title is an affirmation that the future also exists tomorrow, and in all of us. We should start from there.

You’re saying that we owe our children a vision, something to believe in. There is currently a movement underway seeking to give children a political voice. Others think that as a parent, one should avoid giving children definitive answers. Are you consciously going against the trend here?

I believe it’s a complete abandonment of our responsibility if we think that children should find all the answers themselves. We live in a culture that is obsessed with rebellion, where not conforming to established dogma is considered a virtue itself. There are all kinds of reasons why scepticism towards authority makes sense, but it’s as though we’ve taken it to such an extreme that the adults no longer have answers to anything. It’s a ridiculous illusion which has the effect of leaving the young completely alone with the responsibility. All young people take cues from adults in some way, whether through defiance or agreement.

Many adults are weary and anxious because they have lost faith in the future – or at least they talk as if they have. If you go to a dinner party, you might get the impression that the world has gone to hell. All politicians lie. They all have our data. Earth is burning up. This is what many of us adults talk about: the state of the world, wrapped up in edgy statements that are thrown around carelessly. And of course, the children hear it. So, while we pretend that we don’t want to impose our beliefs on them, we risk instilling a kind of nihilistic, postmodern worldview in them. The idea that children should be able to define their own time and world is an illusion, yet the role of the authority figure has become so vilified that we, as parents, don’t want to take it on.

Do you think this disavowal of authority has something to do with a more general rejection of the common history, culture, religion, and institutions that used to frame our world view?

Understanding history doesn’t just mean memorising dates and events. It means putting yourself in a context that is larger than the here-and-now. Not being able to do so can lead to one of the most widespread disorders of the mind today, which is this sense of living in a singularity – of living in a time that is moving faster than ever, that has no reference point, and that slips away between your hands like a social media feed.

It’s not a disorder that comes from people not having read enough books. Rather, I see it as linked to a kind of temporal self-sufficiency: the idea that today is what’s important, that it doesn’t matter what happened before, and that the past is passé and therefore unimportant us.

I don’t have a new narrative for the future to replace the old, dead ones. But I think we need to get some basic principles in place that include understanding ourselves as part of a larger continuous whole. Of course, history is always ideological, so the question is how we can put principles in place that are somewhat universal. That’s one of the questions I try to probe in this book.

Futurists like to say that you can’t understand where we are going by extending the past into the future. Even if we use rationality to understand where we are today, can we depend on it to give us a sense of where we are heading, or do we also need spirituality, mysticism, or perhaps even a wholesale rejection of rationality?

I think it’s true that rationalism is the best tool we have in our attempts to understand the state of the world and where exactly we are right now. But what must come after that is what I will call ‘faith’, understood in the widest sense of the word – and not necessarily in any religious context.

We tend to view faith as some kind of optional add-on, but I think it fulfils a much more fundamental purpose. I see it as a fundamental part of human consciousness, a pre-rational ‘faith’ in meaning or purpose to life. Conversely, there is nothing in rationality that explains or justifies our existence on this planet, or why we get out of bed every morning. You see the shortcomings of the rational mindset in the antinatalism movement, which attempts to reduce the entire world to an equation in order to figure out what it will take for Earth to thrive. It’s nonsense, and a kind of extreme utilitarian approach to understanding the world that doesn’t help us find meaning. In a way, it’s almost like a new Endlösung.

It’s clear that the future is everything but an extrapolation of the past. That’s why my book encourages us not just to think about the future, but to dream about it too. We have to turn on that switch before we can clean up the mess and begin our journey into the unknown.

What would be your message to others who might want to enable their children to dream, or to not mimic the pessimism of their parents?

I’m becoming increasingly convinced that if we owe our children anything, it’s to help them build a will and a purpose in life. Not because we parents have all the answers but because if we don’t provide them with these things, then we are essentially robbing them of the ability to build a meaningful life for themselves.

In a way, I can’t think of a better description of parenthood than being responsible for giving your children structure in their lives – knowing full well that they will reject much of it and that, after having done so, they will be left with the best parts. To me, this a much more interesting way of approaching parenthood than trying to force a coherent ideology or an idea of what is and isn’t true onto them. In structure there is a kind of meaning.

The regretful thing about it all is that it’s not something you can tell your children. It’s something you must show them. That, in a way, is the big test of parenthood. Children don’t do what you say, they do what you do. This was another reason why I wrote the book. It’s not about finding the right things to say; it’s about inspiring by example.

I think we are obliged to try and plant hope in them. My point is that it’s not something we can do unless we find that hope in ourselves first. That’s the brutal truth.

This is an article from

FARSIGHT: Safeguarding Tomorrow

Grab a copy here