In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

For most of human history we believed that everything that could happen, had already happened, and would happen again – ad infinitum. The rise of novel media technologies would change that. From books to computers, the medium with which we record and process information grants us access to history’s forking paths.

Illustration: Sophia Prieto

In the 1600s, the telescope revealed Deep Space, reorganising our sense of place and unveiling a universe far vaster than previously imagined. Thereafter, throughout the 1800s, the geologists’ hammer revealed Deep Time, proving our planet is far older than prior generations assumed. Today, the computer is revealing Deep Possibility. That is, that there’s far more that is possible than is actual.

With the Silicon Revolution in the 1900s came the medium – and the media – to rigorously map what could-have-been and what-could-yet-be. Since then, momentum has built behind a reorganisation of our sense of orientation that might prove of comparable seismicity to those previously unleashed in the domains of cosmography and chronography.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberIt might just disabuse us of residual assumptions of inevitability – of the “unavoidability” of everything making up today’s reality – just as those earlier revolutions disabused our ancestors of presumptions of their spatiotemporal centrality.

For just as humankind’s sense of ‘here’ and ‘now’ has been decentred within progressively vaster volumes of space and time, so too is everything actual being revealed to be a tiny archipelago within an increasingly vast ocean of possibilities unrealised. The following is an announcement of this unfolding and unfinished revelation, tracing it to the development of the computer as a medium, laboratory, and observatory of Deep Possibility.

Counterintuitively, history is interesting – and exerts its influence on the future – because of all the things that didn’t actually happen. It is the entrenching of certain prior possibilities, to the exclusion of others, that explains why the present is the way it is rather than any other way. We only appreciate this fact because we are creatures that produce media that allow us to throw this into relief and make it tangible.

Applied forward onto the future, this insight underwrites all our efforts to shape it. Because actions matter if the consequences they unleash would not otherwise have happened. Understanding this allows us to grasp that the future might play out very differently depending upon present actions or accidents.

This really gains its bite when stretched and extruded through time: when an event in the past – having gone one way rather than any other possible way – shapes all that can possibly come thereafter, in ways that cannot be undone. Such events matter more if their effects are lasting, even more so if they cannot be reversed, or, if they are indelible.

In our everyday lives, we are fluent with ideas of indelibility and contingency. I know that if I injure myself severely enough, I may never stand or walk again; because I also recognise such injury isn’t inevitable, I endeavour to avoid it.

The problem is that we aren’t so used to scaling these concepts beyond our own biographies. Historically speaking, people have persistently underestimated the range of unrealised possibility when it comes to scales more expansive than the tangible and undeniable. That is, until we invented forms of media that provide crucibles for testing this.

For most of human history, it was invariably assumed that humanity’s combined possibilities – the total space of human potential – was small enough, and the time or space available comparatively large enough, that this entire set of possibilities would exhaustively manifest and thereafter recur and repeat without limit.

At the very least, until recently, there wasn’t yet the evidence to satisfactorily disqualify such assumption. Sometime around 300 BC, Aristotle accordingly declared that “each art and science has often been developed as far as possible and has again perished”. He held this has happened “not once nor twice nor occasionally, but infinitely often”.

This outlook entails that what is accomplishable in the future is bounded by what has been achieved before: because all human possibilities have already been manifested, such that, unprecedented, systemic change is impossible. Humanity’s future, on this view, cannot come to look dramatically different from its extended past. It’s understandable people used to assume this, given the pace of technological or social change was imperceptible within one lifetime.

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereIt’s why Thucydides, writing a couple of centuries prior to Aristotle, thought that chronicling history was indefinitely instructive for the future: precisely because possibilities are “repeated”, such that “human nature” never truly changes.

This was tied to a conception of possibility popular throughout the premodern world, which defined it as “that which sometimes happens”. This was by contrast to necessity, defined as “that which always happens”, and impossibility, as “that which never happens”. Elegant as this is, it obstructs articulation of possibilities that have never once happened before. This, by consequence, truncates the conceived space of total possibility to trivial rearrangements and circulations of what’s already been precedented.

Throughout the later Middle Ages, Islamic Ash’arisites and, later, Christian voluntarist theologians became eager to buttress their conviction in divinity’s omnipotence by articulating all the ways the world could have been forged otherwise. This motivated them to produce logical definitions of possibility unmoored and unanchored from precedent, or, manifestation within time.

This emancipated possibility from prior realisation within time, cleaving open a new space for imagination no longer barricaded by the blinkers of human precedent. But the belief that Deity elected ours as the best of all possible worlds and was bound to uphold this plan over any others possible, meant there wasn’t yet sensitivity to the ways our own world might actually become drastically different – hinging upon current happenstance.

The domain of ‘otherwise’ had begun being cognitively mapped; but it was not yet applied to time within this world; instead, it remained quarantined, to timeless relations between untouching worlds.

Loosening the grip of providence over worldly affairs took time. This was because the expectation that things were unfolding according to a divine plan didn’t dissipate upon its first frustration. Christianity and Islam both taught – apocalyptically – that history was much nearer its ending than its beginning: that the denouement of creation was near and its date a matter of predetermined destiny.

But, as the Middle Ages rolled into the Renaissance, no such culmination or apocalypse manifested. Chronicled time was dragging on, swelling beyond the bookends prescribed by apocalyptic prophecy. The more the years piled up, and the more frustrated their supernatural termination became, the more there could arrive a sense of the autonomy of secular history from divine orchestrations.

This fed into, and was fed by, building conviction that genuinely unprecedented things were being innovated and wrought. Human ingenuity – rather than divine dictatorship from the heavens – seemed, increasingly, to be steering history’s course. So, too, did a suspicion begin building that time is open-ended: that is, that it can take various different tracks, depending on accident and agency flowing from human affairs.

So mused French polymath Blaise Pascal around 1650: had the “nose of Cleopatra” been different, then “the face of the entire world would have been changed”. That is, should Mark Antony not have fallen for Cleopatra’s distinctive visage, subsequent events would have also been unrecognisable. With this clever quip – bundled with a pleasing pun – Pascal captured an emerging, very modern attitude towards time.

We may be accustomed to such counterfactual conjectures at global scale now; back then, however, they were newfangled. Our grasp of history’s contingencies, and of the future’s forking paths, has continued growing ever since: an everexpanding halo of unrealised possibilities fanning out from the merely actual.

Nonetheless, Pascal himself held to the old belief that the space of historical possibility was small enough that everything that can happen already has happened, such that true unprecedented change – in secular affairs – remained unthinkable to him.

Similarly, Sir Thomas Browne – writing around the same time – pondered history’s critical moments, imagining what would have happened “if” each had gone differently. In particular, he considered how things would have played out had Alexander the Great conquered the Romans, rather than the Persians.

Browne found this counterfactual conjecture curious, but he denied any legitimacy to it. For the Roman empire had to prevail in order for the “advent of Christ” to unfold. Because our “Saviour”, Browne concluded, “must suffer a Jerusalem, and be sentenced by a Roman judge”.

Though its roots go back to the theological arguments of the late Medieval era, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz is famous for developing the theory of “possible worlds” in his Théodicée of 1710. But, crucially, these evanescent possibilities were hermetically sealed from our world. Leibniz, again, believed ours, by necessity, the best. Accordingly, when it came to worldly history, he held a very providentialist view: remarking – after considering some critical counterfactuals – that the “instants of when things should happen” are, ultimately, “set by God”.

What’s more, in a fragment penned in 1715, the German polymath set out to gauge the total set of human historic possibilities, with an eye to calculating the interval of time before worldly history resets and repeats itself.

Beginning with the premise that one can “determine the number of all possible books of a given size composed of meaningful and meaningless words”, Leibniz noted this number is finite. Supposing, therefore, that “a public annual history of the earth can be sufficiently related” in a book containing “100 million letters”, he concluded it is “clear that the number of possible public histories of the earth” is “limited”, because the number of meaningful combinations of 100,000,000 letters is finite. Accordingly, given enough time, human possibilities will “exhaust” and repeat. Leibniz remarked that the monarchs of his day – from Emperor Leopold I to King Louis XIV – will “return”.

Going even further, he pronounced that the same calculation can be conducted for our own “private” histories. Supposing a “thousand million humans” alive on Earth, he guessed that a book with 100,000,000,000,000,000 characters could exhaustively chronicle every experience of every human over the course of a year. Again, given that the number of meaningful permutations of a book of this length nonetheless remains finite, Leibniz pronounced that every individual life is bound to repeat, down to the smallest minutiae. “I myself, for example, would be living in a city called Hannover”, he mused, “writing letters to the same friends with the same meaning”.

Leibniz wasn’t explicit on the interval of time required for this recurrence to occur, but he was certain it could be meaningfully numbered. Notably, at the time, the entire span of Earth history was often measured in thousands of years, with some outliers admitting the possibility of tens or hundreds of thousands of years.

It’s natural that Leibniz deigned to measure history’s possibilities with the most predominant media artefact of the time: the book. The spread of printing was a precondition to the rise of the novel, throughout the 1700s, as the primary form of storytelling. Given their format, novels are inherently linear: appealing to the view that things can only go one way.

Nonetheless, by more or less explicit comparison to divinity itself, the novelist became a demiurge who selects one course of affairs from a far wider range of possibilities. Partly inspired by Leibniz’s ideas, the German aesthetician Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten remarked in 1735 that the author engages in “secondary creation”: forging a “heterocosm”, a world wherein things are otherwise.

Naturally, the proliferation of the media enabling such “heterocosmic” conjecture would also help nurture awareness of all the ways things can play out differently. An increasingly capacious sense of how this applies to the past, in a manner determining the visage of the present, widened a sense of the open-endedness of the future ahead. ‘Possibility’ gradually transposed from timeless differences between untouching worlds toward temporal developments, and branching paths, within this world. Appreciation of historical change – and the undecidedness of the future – strengthened.

Accordingly, the genre of ‘alternate history’ began to recognisably coalesce during the 1800s. Emerging from military history – where critical decisions and counterfactual outcomes are obviously salient – the endeavour reached a kind of early culmination in works like Charles Renouvier’s 1857 Uchronia: An Apocryphal Historical Sketch of the Development of European Civilization as It Wasn’t but as It Might Have Been.

One of the first novels to provide a book-length treatment to an alternate history – applied to the entire continent of Europe – it is telling Renouvier’s book was published two years before Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species was unleashed upon the world.

Darwin split history in two. His seismic contribution rested in a radical break with prior assumption, which broadly held every species that could exist necessarily, at some point, did. He recognised, contrarily, that, of all the organisms which can exist, only a vanishing few ever have or will. This way, we can suddenly explain – in the thickest sense of the term – why life looks the way it does rather than any other way. It is because only a select few creatures produced offspring in the past, whilst others didn’t, that tells us why life is variegated as it is today. It is because certain ancestors persisted and propagated to the permanent exclusion of other possibilities.

Darwin’s revolutionary insight, therefore, rested in apprehending that what’s organically possible is far vaster a kingdom than what is organically actual.

As the 1900s opened, and the biochemical foundations of life began being understood, the sheer scale of these unrealised alternates began being sensed. The geneticist iconoclast J.B.S. Haldane, in 1932, guesstimated that, even if humans persisted for a trillion further years, this wouldn’t provide enough “to breed one each of all the theoretically possible varieties of Drosophila melanogaster” – that is, the common fruit fly – nor “to synthesize all the possible organic molecules of a molecular weight less than 10,000”.

Leibniz had, in part, desired an exhaustive set of historic possibilities – embodied in a printed book — because he didn’t know that human potentials were themselves generative entrenchments of a wider evolutionary history. Human potentials aren’t dictated from outside of time, but were generated within it. They are conferred by countless prior preconditions, each of which could have gone otherwise, in turn altering the affordances inherited and, thus, immeasurably multiplying the range of what could have been.

This, in tandem, undermines the assumption anything like us was inevitable – which, for most of history, has been the default. Not being able to touch or taste all the other possibilities, it’s easy to think of one’s parochial actuality, and one’s own existence, as the only available – thus, unavoidable – possibility.

But, by and large, the true weight of this didn’t sink in until well into the 1900s. The reasons for this are myriad and complex, but one may have been the lack of the media to make it tangible. That is, until the proliferation of the electronic computer.

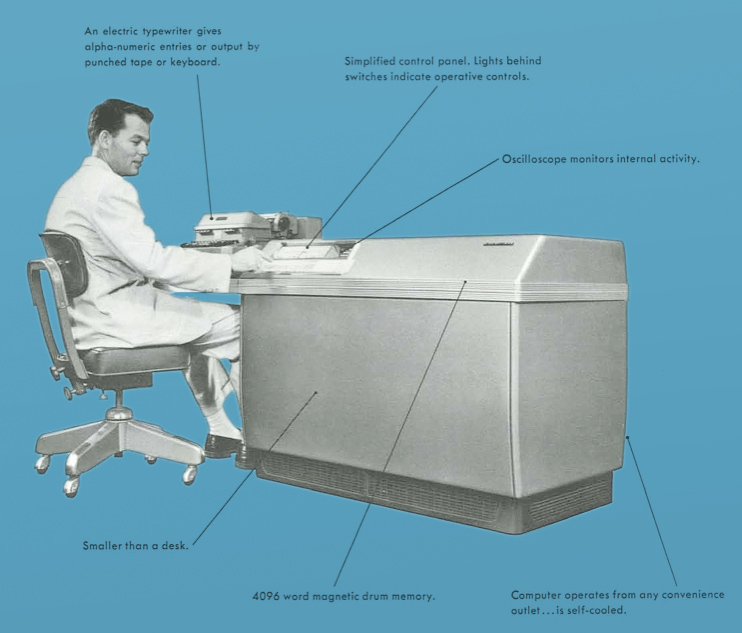

Like the telescope and microscope before it, the computer opened new vistas for humanity. Namely, the land of alternate pasts and their branching futures. For the first time, in the mid-1900s, electrified silicon allowed scientists to access and map the elusive realm of what-could-have-been and begin to probe its outer regions.

Simulation reverse-engineers nature’s laws in order to model its processes in miniature. By enabling replays of time’s tape, the computer turbocharged the insight that the actual course of events is often only a smaller subset of what’s truly possible. It splays the previously linear track of the novel – and, later, the film – into the branching path that more accurately emulates the nature of things.

Outsourcing the task of visualising parallel plays of the past and future, by delegating it from our unreliable brains to unbiased numbers, helped prove that what actually happens hardly ever exhausts the totality of what can.

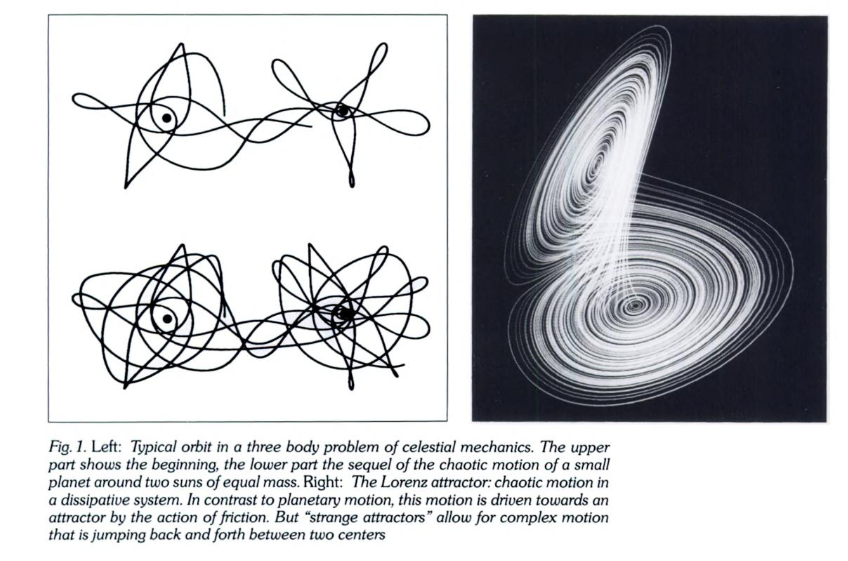

It was the computer that proved that, even if they operate fully deterministically, the ways complex systems develop can be unpredictable in advance. Edward Lorenz, Ellen Fetter, and others stumbled upon this truth, and pioneered chaos theory, by messing around with weather simulations on an early commercial computer in 1961. There are many more ways things can unfold than initially there might seem; but it took vacuum tubes and, later, semiconductors to tangibly demonstrate this.

It is also no coincidence that some of the first biologists to explore the more radical implications of evolutionary theory were also some of the first to deploy computer techniques in their field.

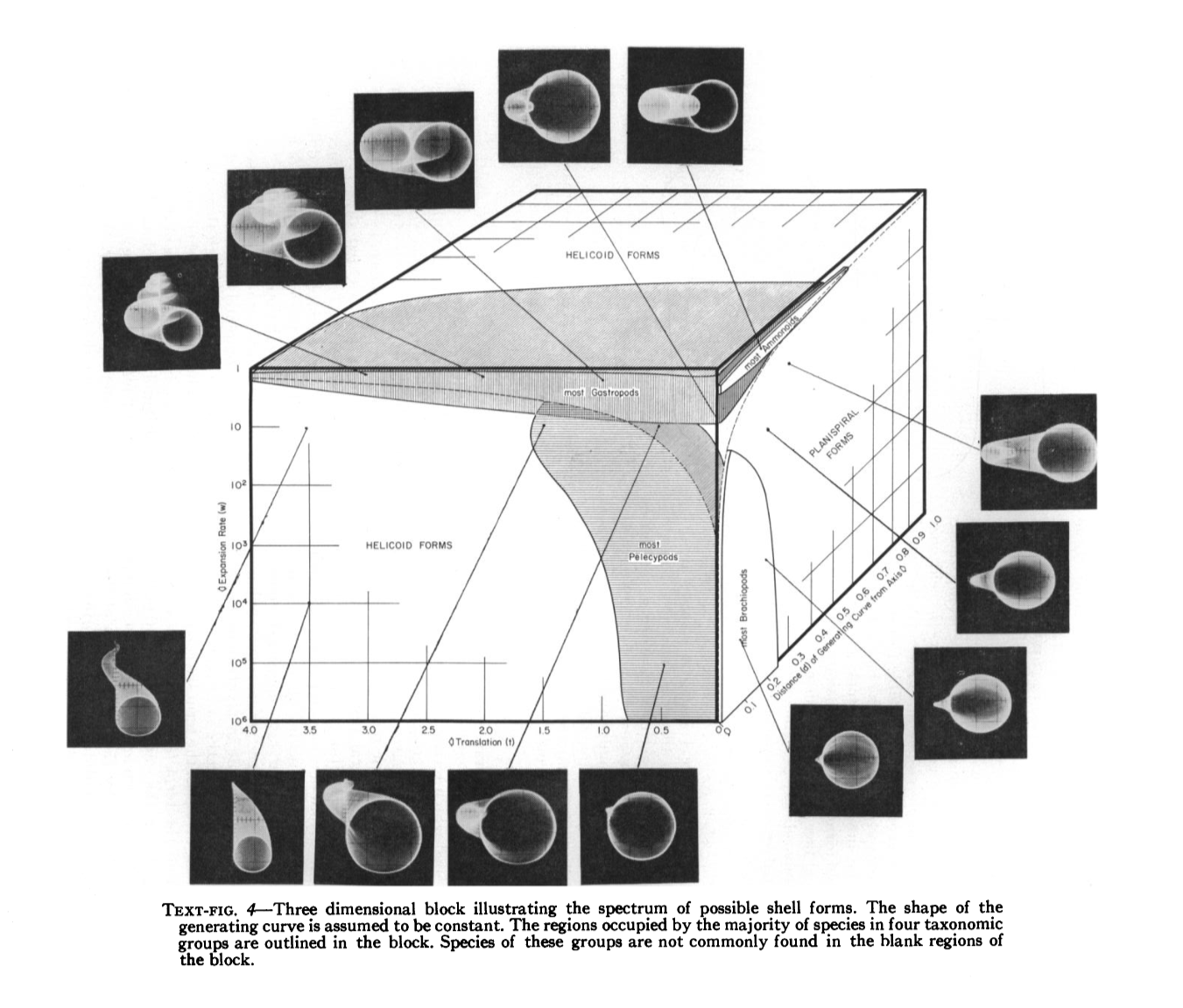

One such example comes from David. M. Raup: a Bostonian palaeontologist, who, in the 1960s, made waves by applying computer techniques – conscripting his bulky IBM 7090 – to show how the shells of actual seasnails occupy only a small region within the much wider space of possible morphologies. Raup called this a “morphospace”. He had used his IBM to access the previously intangible, world of what-could-have-been.

Following his tests with seasnails, clearly with a strengthened confidence in the spacious superfluity of what’s possible above what’s actual, Raup and his colleagues – like Stephen Jay Gould – began applying similar techniques to macroevolution itself. Proving that the medium precedes the message, they began asking what would happen if we “replayed the tape” on life writ large: rewinding to its earliest beginnings, and tracking forward, to assess whether the outcomes would be recognisable or unrecognisable. The “tape” metaphor was apt: computers, back then, used magnetic tape to generate their heterocosms.

In a 1983 paper, Raup and his coauthor J.W. Valentine pushed this even further. They wrote:

Life forms are made possible by the remarkable properties of polypeptides. It has been argued that there must be many potential but unrealised polypeptides that could be used in living systems. The number of possible primary polypeptide structures with lengths comparable to those found in living systems is almost infinite. This suggests that the particular subset of polypeptides of which organisms are now composed is only one of a great many that could be associated in viable biochemistries.

Remarking that there is “no taxonomic category available to contain all life forms descended from single event of life origin”, they proposed the term “bioclade”. Assuming, as all the evidence indicates, that life on Earth shares one common ancestor – thus is “monophyletic”, forming one “bioclade” – we can assume that every single organism we are familiar with occupies just one miniscule mote within an unthinkably wider space of possibility. Sounding out the proportions of that morphospace – of all possible bioclades and their splaying histories – remains a riddle for future synthetic biologists and astrobiologists.

Raup concluded by turning Leibniz on his head. He remarked that what is safe to conclude, for now, is that it is “most unlikely” that “our bioclade is the best of all possible bioclades”.

The tenor and tendency of modern inquiry – supported by modern media, coupled with the creation of ever-more-potent heterocosmic crucibles – appears to be the revelation that what’s actual is but a shrinking region within a growing kingdom of things that could have been, but simply weren’t.

Of course, Leibniz’s desiderata remains: that with enough knowledge, time, or computation, we might be able to brute force history’s complexities, so as to produce a perfect predictive model. But the past teaches us that every prior generation has been reliably proven overhasty, time and again, in assuming they had come anywhere close to grasping history’s entire span of possibility. The latitude of the unrealised belies our parochial tendency to assume what’s actual exhausts what’s possible. But, as generations before were displaced in space and time, we appear – for better or worse – to be dethroned in wider realms of possibility. Perhaps this is salutary. Unpredictability has long been considered an aesthetic virtue, after all.

Gran Allen – a Canadian science writer and communicator of Darwinism – put it best, all the way back 1886:

It is the common error of the human species to underestimate the vast and wonderful complexity of nature, [and to] overlook the whole enormous series of remote consequences that follow [upon] every act. […] Whatever we do entails far more than we ever imagined, and carries with it an entire sequence of distant effects whose very existence we never counted upon.

This article was first published in Issue 13: The Generative Future