In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Worldwide digital connectedness increasingly resembles an external brain, and the ability to perceive the digital world has become indispensible to us. Is the tree of evolution sprouting a new branch?

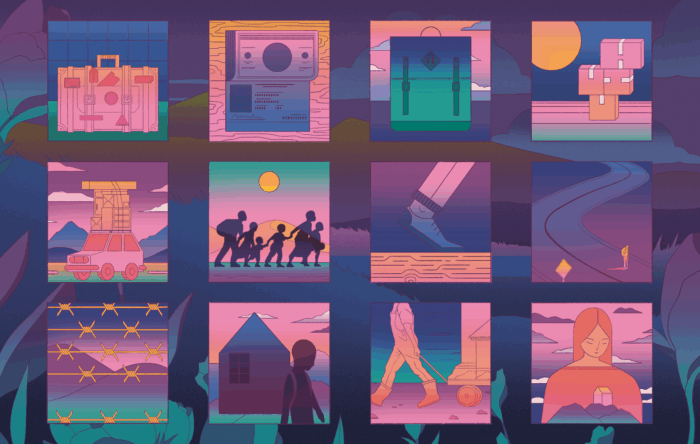

Illustration: Ming Sin Ho

Some changes are so big that we can hardly see them: The human species, Homo sapiens, is beginning to branch out. At a fairly rapid pace, humanity is acquiring a new set of traits, in what may best be understood as the emergence of a new species.

We are developing the ability to sense a type of signal that didn’t exist a few decades ago – digital data. This emerging sense allows us to perceive a new reality we are busy constructing: the digital world. As this realm grows, it is becoming nearly as vital to our wellbeing as the physical one. Our ability to think, analyse information, and our memory will be dramatically enhanced by our tight connection to a vast computing network.

This digital net, and the devices we use to connect with it, will effecticvely be an expansion of the human nervous system and brain. Because we are all connected, individual humans will become like cells in a shared, global organism – half biological, half technological. That evolution will change our lives to the point that those who are connected to the organism will have very little in common with those that aren’t.

For thousands of years, Homo sapiens – ‘the intelligent human’ – has been Earth’s dominant species. Our dominance is in part thanks to evolution endowing us with a novel brain structure, the frontal cortex, where analytical thinking takes place.

We are now developing another addition to our brain, but this one is not enclosed inside our skull. It’s an external brain, residing in massive data centres with rows upon rows of the most powerful processors available.

The human monopoly on analytical thinking has been broken. Now, computers also analyse their surroundings, find patterns, test hypotheses, and construct models for how the world works.

However, ‘machine learning’ is a different intelligence than our biological kind. A computer learns much faster, and everything it learns it can share with other computers in its network. Likewise, the digital brain and nervous system that separates the new human from Homo sapiens is shared by many humans – millions if not billions. In this sense, the new human is less of an individual, and more like a cell in an organism.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberIt remains uncertain whether all human traits can be replicated by a computer. But so far, we are moving ever closer to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) – the stage, at which machines can do virtually everything humans can. Briefly; once that threshold is crossed, they may speed away from us entirely. Enormous resources are dedicated to achieving this, and AGI is a top priority for some of the world’s biggest and wealthiest companies.

We perceive only a fraction of what happens around us. Many animals possess sensory abilities beyond human reach – birds navigate using Earth’s magnetic field, bats rely on echolocation to hunt, and insects can see ultraviolet light.

The new human’s ability to perceive the digital dimension can be thought of as a unique seventh sense – a capability no other animal possesses. Just as a dog relies on its sense of smell, this digital sense has become essential to us. As we construct a world where digital events have tangible, real-world consequences, our connection to this emerging realm is indispensable. Today, we interact with the digital dimension through the screens on our computers, smart phones, and other devices. Over time, these devices will become increasingly integrated with our bodies. Technology will no longer be separate from us – it will become a part of us, and we, in turn, will become part of it.

We will work, socialise, learn, and conduct warfare in a mixed reality, and the ability to sense and navigate both dimensions will be crucial to our wellbeing and survival.

Already today, our dependence on technology starts early. Every ninth Danish child born is conceived through artificial means, and this number is growing. Even before birth, many foetuses undergo DNA testing and countless detailed scans are taken to ensure that nothing is out of the ordinary. By the age of two, many children can use an iPad. Soon after, they get their first phone. Before long, children – even the yet unborn – will be permanently connected to the digital system. Being online will be part of their nature.

At present, we need devices for our digital sense, first of all our phone. Without it, we are as handicapped in practical terms as if we were missing an arm or a leg – whether it’s for doing our jobs, shopping, finding our way, or communicating with others.

We are psychologically dependent as well. Most of us rarely spend more than a few minutes without checking social media, scanning the news or sending an email. Like an alcoholic or chronic smoker, we can’t beat the addiction, even when it’s clearly detrimental to our quality of life.

For the new human, however, this dependency is not merely a distraction or a bad habit. Rather, it’s a natural and necessary part of our being. Having outsourced some of our senses, our memory, and our thinking to the digital nervous system, we must remain in constant communication with it.

It’s not new for humans to outsource some of our abilities to technology. With fire, we could cook food, easing the burden on our digestive system. With machines, we amplified our physical strength. Not long ago, we navigated by the stars or a map. Perhaps the ability to speak other languages will be the next skill we outsource to machines – one that, over time, may fade from our biological repertoire.

Many of us depend on assistive devices like glasses, hearing aids, or pacemakers, just as our wellbeing – and survival – depends on medicine. One in every eight Danes use drugs to treat depression, insomnia, psychosis, or ADHD. Such medications makes a significant difference in how a person experiences the world and how others experience them.

Prosthetic limbs are technological marvels that can be directly connected to the user’s nervous system. The next level could be exoskeletons designed for heavy lifting or to help individuals overcome physical disabilities. Nanobots, another bodily upgrade, will be able to travel through our veins and repair defect cells or clean and restore us from within.

The technological evolution is taking us from relying on external devices – easily detached and replaced – to permanently implanted technology. This will include brain electrodes connected directly to the nervous system.

Brain Computer Interfaces (BCI) that allow the movement of prosthetic limbs simply by thinking already exist. Over time, such implants might allow us to communicate directly with the digital dimension and control myriad devices connected to the global organism. With higher resolution and improvements to bandwidth – one of the most stable long-term trends in digital technology – it will be possible to transmit much more complex and detailed sensory impressions.

One can only guess how this might change how we think, sense, learn, and communicate. Our inner thoughts and reflections may become transparent and part of our interaction with the system. What we experience could be entirely synthetic – transmitted directly to our sensory system as a fully simulated experience. Distinguishing between our own thoughts and those of the machine becomes increasingly difficult.

Long before that happens, our perception of what is real and authentic and what is synthetic and fictional will start to change. Determining whether something belongs to one category or the other will start to become meaningless.

Humans, machines, and other objects will have “digital twins”; a collection of data describing who they are, their history, and their status. Whether it’s a car, a building, or a person, an ever more detailed log of everything they’re involved in is continuously recorded. Together, these digital twins will form a kind of digital mirror world that can be navigated and probed using our new senses and skills.

Our new “natural” habitat will include ultrarealistic computer-generated worlds rendered in real-time and populated by avatars and agents. There will be universes which we can be completely immersed in, or we will sense data as an augmentation of the physical dimension – a layer of information superimposed on our field of vision and hearing – a “mixed reality.”

Our understanding of what it means to “be present” will change. With a constant connection to the digital nervous system, our presence will no longer be limited by our physical body. We will meet, have experiences, and be able to act and operate devices and equipment without any geographical constraints.

We all draw on the same global data stream, delivered by the same giant corporations.

But paradoxically, alongside increasing global connectivity and integration, there is a trend towards fragmentation: we each receive different subsets of the data stream, resulting in vastly different perceived realities. The internet has turned into a “splinternet” – divided into parallel universes, each with its own set of local services, norms, and rules.

Despite the current slowdown in global integration, we continue to exchange ever more data and knowledge at the local, national, and regional levels. We become more interdependent – not only digitally and electronically, but also as we face ever more urgent and global problems. Chief among these is our disastrous overuse of Earth’s resources, undermining the capacity of ecosystems to sustain life. Our greatest challenges are shared.

It’s ironic that we, especially in the Western world, place such great emphasis on individual freedom. Supposedly, individualism, competition, and self-interest are what drives rational man – the main protagonist in economic theory.

Once, when we lived on the vast savannas, it may have made sense to view oneself as completely free and independent. But if we want to achieve something that goes beyond our own individual capabilities, we must cooperate and coordinate with others.

The larger our population grows, and the higher living standards we seek, the more we need to use the planet’s resources efficiently. The more complex and widespread humanity becomes, the more we will need close coordination, regulation, and adjustment of our actions for the common good to function.

More than ever, the new human cannot stand alone. Again; we are like cells in a body – bounded units, but unable to survive outside the larger organism.

It’s not just people who are being interconnected. Our devices and machines are also becoming more closely linked, forming large systems where each technological node in the network – “the Internet of Things” – acts as a component of one big machine.

Our surroundings will be intelligent in the sense that many of the objects around us will be “smart”: they will have sensors, a chip to analyse signals, and a connection to the collective system’s information and computing power. They will know who we are and what we want. They will learn, understand patterns in our behaviour, and coordinate their interactions. They will draw on the same computing resources and data – the same system we ourselves are a part of.

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereThe new human differs from Homo sapiens not only because we are so closely interconnected that we share a nervous system with our fellow beings. Equally important, we humans will share that nervous system with all the gear and countless smart objects we acquire and install.

With an implanted interface between the body’s nervous system and the digital system, humans themselves become part of the Internet of Things. Just like cars, toasters, and buildings, we are interconnected and we will constantly exchange signals with everything and everyone around us to adjust our actions.

A child born today still has the same genes as someone born 50,000 years ago, but within a few decades, that may change. Biological modifications to humanity will come along somewhat later than the digital expansion of our nervous system, but it seems unlikely that we won’t begin to alter our genetic makeup eventually.

Initially, genetic interventions will be aimed at preventing diseases and compensating for defects, limited to individual patients. The next step will be to edit germ cells, so that any genetic change is passed on to subsequent generations. Such interventions might eliminate a genetic defect once and for all. After that, it will be tempting to move on to changes that can enhance or modify a person’s abilities – whether that means higher intelligence, resistance to viruses, stronger physical traits, or purely cosmetic changes. In short: designer babies.

Our genes are the result of billions of years of evolution. That evolution has been slow and based on random mutations and genetic selection. Natural evolution has neither direction nor intention – it simply adapts continuously to changing conditions.

The changes shaping the next human are not random but rather the result of conscious, systematic interventions aimed at achieving particular new traits. With the ability to rewrite the very code of life, the technology-driven evolution will move much, much faster in whatever direction we ourselves consider advantageous.

Yet technological changes are themselves driven by evolutionary pressure. The technologies that flourish are typically those that do well in capitalist economies, or that can be used to seize and maintain political power. Those same ambitions seem to shape the development of humanity’s new traits.

Our digital nervous system may be shared, but it is owned by a handful of major companies and governments deciding who has access, how much this access costs, and what is allowed or possible. Not all cells and organs in this global organism are equal; we will have different technologically determined capabilities. However, factors beyond money, power, and aesthetics may prove more crucial to our long-term survival as a species. Despite the digital superstructure layered on human reality, we remain entirely dependent on our surrounding ecosystems and biosphere.

The climate and the global environment are also changing rapidly – and not in a direction that seems favourable for humanity. Large parts of the planet could become uninhabitable due to heat and extreme, unpredictable weather, which will challenge our ability to adapt, while opening possibilities for new species better fit to new planetary conditions.

And then there is space. Who knows – future humans may need to function without gravity, under intense radiation, and with the ability to hibernate during yearslong journeys.

One definition of different species is that they do not interbreed. They don’t understand each other; they have no shared community, in fact they may compete for habitat. It’s hard to imagine how a marriage could function between someone who lives in direct and constant contact with the digital nervous system and someone who is more hesitant and rooted in the physical world.

This is the division that arises when the evolutionary tree sprouts a new branch. The question, then, is whether humanity will split – with some choosing to follow the technological path and become part of the global organism, while others opt out or lack access to it? And if we do split, will one species outcompete or eliminate the other, taking over its ecological niche? It would not be the first time in human history.

The new human does not suddenly appear, fully formed and alien. It’s an evolution – a gradual change. Just as Homo sapiens still shares 98 percent of its genes with chimpanzees, the new human will, in many ways, be very much like us.

And yet completely different. The new human will be a cell in humanity’s global organism, connected to a digital nervous system that takes over much of our thinking and gives us new senses for experiencing a digital dimension that is just as significant as the physical one.

These transformations are already accelerating and reinforcing themselves, and one day we will be so different that we will no longer be Homo sapiens. Just try extending the trends in biotechnology, artificial intelligence, and digital technology fifty years into the future – can we still be the same humans then?

This article was first published in Issue 13: The Generative Future