In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

With artificial intelligence comes radical change in how information is both created and retained. What place do humans have in future knowledge ecologies?

Illustration: Sophia Prieto

In the last hundred years, humanity’s capacity for knowledge transmission progressed from the written word and the static-laden echoes of early radio technology to global information systems so vast and complex that no single person on Earth can claim a complete understanding of them. Inevitably, the social technologies built into both our biology and our society are no longer entirely capable of addressing our new epistemological landscape. But is a slow retreat into the machine necessarily the only path we can take to keep up?

In L. P. Hartley’s 1953 novel The Go-Between, a young boy, Leo, becomes the unwitting bearer of messages between two members of English high society. Leo’s age makes him usefully naïve, and he has no idea that the ‘business’ messages he carries are in fact the groundwork of a scandalous and illicit affair between the two. Long after the truth has inevitably come out, an older Leo reflects on the experience of being a transmitter of knowledge, or a node in a larger network, and concludes that the action of carrying socially coded information has irreversibly shaped his own engagement with the idea of intimacy and connection. He returns to his childhood estate and the last living participant in the affair once again persuades him to carry messages – this time between her and her daughter – because Leo is the only one alive who still carries any memory of it happening at all, and is therefore the only one able to bear witness and legitimise the intimacy and morality of history.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberThe idea that human beings function within wider systems as not only sovereign beings but as knowledge repositories, interchangeable with the non-human, is not a new one; it dates back at the very least to the beginnings of the study of cybernetics.

Norbert Weiner’s Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (1948) established the idea of regulatory feedback processes as a basis for mapping the living organism as a system – all the way from the most minute cellular processes to the largest macrodynamics of ecosystems. Project Cybersyn, which was an attempt to operationalise the economic planning of 1970s Chile as a cybernetic system, was a proposed assimilation of human decision-making and emergent sources of low-latency economic data (envisioned in the form of a vast room with many flashing panels – not dissimilar to those of the Discovery One spaceship in 2001: A Space Odyssey).

Cybernetics has remained a compelling idea, and indeed as communications tech- nology develops and entrenches itself further into our daily lives, our capacity for data-based decision making through things like prediction models and machine learning can only be expected to increase. Knowledge production may have become synonymous with the use of digital technology. But what are the potential outcomes for human knowledge – not just lived and subjective experiences, but our capacity to both carry and transmit it?

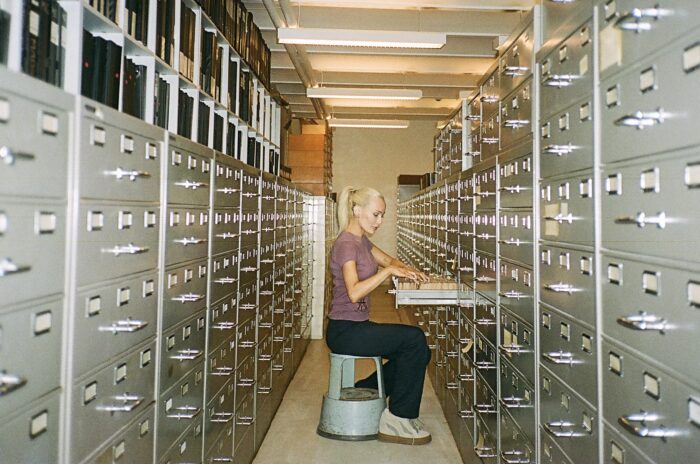

The French philosopher Bernard Stiegler, writing in the 1990s, put forward the idea that after primary and secondary retention (what you experience and what you remember experiencing) comes tertiary retention – the notion that human memory is collectively preserved in tools, texts and media. The amalgamation of tertiary retention is what actually contributes to the shape and nature of culture and society over time. This means that human memory has always been co-constitutive with technical systems, whether that was the process of using clay to draw animals on cave walls, or keeping family photo albums.

The development of technologies for the purposes of tertiary retention has, for the most part, been on human terms. But today, we have perhaps reached a tipping point where the architectures of knowledge are developing in service of the nonhuman superstructure.

One of Steigler’s primary concerns was the automatization of thought and knowledge production as a result of the datafication of externalised memory. Our primary and secondary retention – immediate and recalled experiences – become influenced by technologies of tertiary retention. For example, you may take a photo in a way that ensures that it will be later recognised and categorised by AI, or describe yourself in a job application in a way that will pass automated systems, which in turn, impacts your own sense of self.

Existing knowledge architectures have, of course, been radically altered in a relatively compressed timeline. OpenAI only released the first public-access version of ChatGPT in 2022, but the fallout of this product is already changing the way knowledge is generated, treated, and shared. Among the effects this has on our primary and secondary retention is an observed ‘flattening’ of language, with public-release LLMs teaching the world how to communicate in a new, universal style that is stripped of both linguistic nuance and cultural specificity. Currently, most LLMs rely on human-generated training data for their language synthesis. A future in which some of this data is inevitably tainted by LLM-produced linguistic structures (known as the problem of synthetic training data) may see the snake begin to eat its own tail.

If AI, to some degree, represents an automation of thought, then there is a push to elevate this at a state level; in the US, the Trump administration is promoting legislation and directives that would usher in a “golden age of AI”, with President Trump signing three executive orders in July 2025 alone “to sustain and enhance America’s global AI dominance in order to promote human flourishing.” Whether or not the AI bubble bursts remains to be seen, but its effects on our short-term memory storage and knowledge production have already been felt.

In this accelerated landscape, what are some potential scenarios for the future of human tertiary retention? One of the original stated goals of Elon Musk’s Neuralink venture was to “achieve symbiosis with artificial intelligence” – achieving a ‘conscious’ AI by fusing a synthetic implant’s AI-based thought functions with human brain-based decision-making and making human-digital knowledge interfacing more seamless. Essentially, if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

Sam Altman’s World Network represents an interesting outcome of an economy rushing to monetise solutions to emergent problems increasingly caused, in that same economy, by automated knowledge. To solve the issue of determining whether or not a thinking agent is human or not, the company offers the voluntary scanning of a human iris which is then converted into a cryptographic hash. This is done via an ‘Orb’, a somewhat science-fictiony silver scanner. The end goal is a unique and universally verifiable proof of human identity, unfettered by the influence of any single state. The Worldcoin Token, an Ethereum-based cryptocurrency, is distributed to every registered user as a reward for signing up. Understandably, World has run into widespread regulatory barriers. Yet its existence is an interesting example of the problems with automated knowledge that the market will need to solve in future.

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereSteigler wrote prolifically, but one of his last works before his death in 2020 was The Neganthropocene (2018), an update, and perhaps also a call to action, based on the near-thirty years between his first writings on the dangers of a global tertiary retention, focusing solely on technocapitalism. Steigler writes that we currently sit on the precipice of the end of the Anthropocene; the future of knowledge may be more inhuman than it is human. Currently, human development has become its own geological force, destabilising ecosystems. He views this condition as pharmacological (containing both the poison and its cure) wherein the capacity to produce climate-destroying innovation also enables far more beneficial outcomes: solutions and the potential for caring and healing knowledge architectures.

The possibility for this duality exists both internally and externally to nature. Just as technological development can destroy one ecosystem, it is equally capable of forming a cognitive ecology that values collective action for continued survival. Capitalising on this healing aspect of communications technologies is not just the case of a colony of bees sharing knowledge architectures with a colony of ants; it is about entering into a conscious and consenting wider technocultural assemblage that does not rely solely on datafication. It may not require capitulating to the machine, as with Neuralink or World, but rather reinterpreting our relationships to digitised collective memory.

Concurrently to Steigler’s work, during the 1990s the cognitive anthropologist Edwin Hutchins began to develop the approach that would become known as ‘distributed cognition’, which also became the basis for the group of theories known as embodied cognition. Essentially, Hutchins argued that across cultures, we outsource cognitive processes to solve collective problems. It could be as simple as two people working on a maths problem, or as complex as using millions of global databases to geolocate a needle in a haystack. The early LAN computer networks of the 1970s laid the foundations for the widespread incidence of humans outsourcing distributed cognition to machines. It is only recently that the knowledge passed between those machines has begun to have a nonhuman epistemological basis.

An often-used example of distributed cognition is the Galaxy Zoo project, where in 2007, the general public were asked to help classify galaxies based on images from large-scale telescope surveys. The call received millions of volunteers, and the human input was used to train future image-recognition machine learning programs. In 2023, the ‘Zoobot’ was added to the project, which bulk-classifies easily identifiable galaxies while leaving the more complex and interesting ones for humans to classify. Zoobot’s training data came from nearly two decades of distributed human input.

Today, medical imaging (such as retinal scans) and protein-discovery tools like AlphaFold form complex relationships between bulk-processing tasks – done digitally – and situational or anomalous human oversight. Perhaps this perfectly represents the positive side to the pharmacological transition period we currently find ourselves in; intelligence, cognition and the knowledge they produce are not limited to the processes contained inside a single organism (there are many examples to the contrary in nature). but as new cognitive infrastructures and interfaces, such as AI, begin to form, the processes Stiegler foresaw may become accelerated in extremely interesting ways as new artificial, cognitive ecologies emerge.

On the surface, we are facing questions of governance, control, and perhaps identity as digitalisation continues without any sign of reaching a saturation point. But at an underlying level we may be simply arriving at the realisation that cognition and in turn knowledge, while its conditions may still be reliant on us, will no longer solely belong to us.

This article was first published in Issue 15: The Future of Knowledge