In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Recent events have contributed to declining trust levels in major public and private institutions across much of the world. These same institutions are now in a position where they will be forced to re-think their current trust-facilitating models. The proliferation of new trust-enabling technologies will further change how trust is facilitated and maintained in our digital age. The question is whether traditional institutions will be able to overcome their “trust inertia” in time.

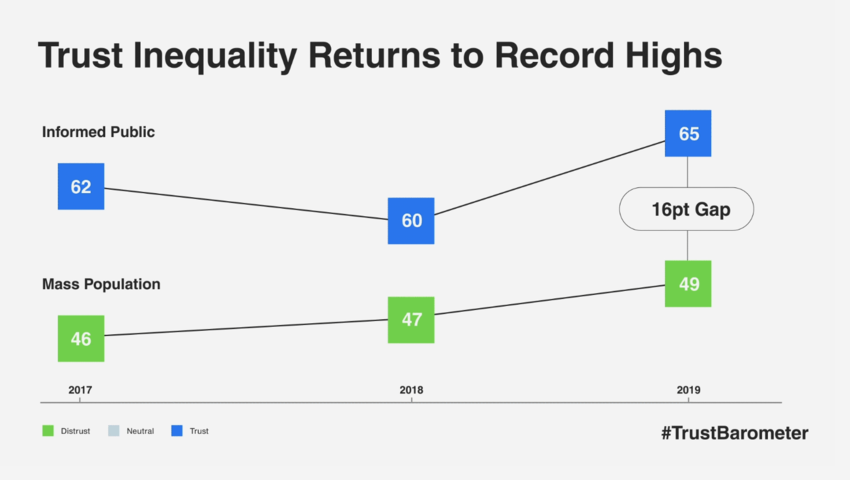

In recent years, society has struggled under a tremendous accumulation of trust breaches from institutions whose core purpose, ironically, is to serve as facilitators and safeguarders of trust. It comes as no surprise that the acclaimed annual trust survey published by Edelman shows that citizens’ trust in government, business, media, and NGOs is hovering at an all-time low around the world. “An Implosion of Trust” was the dire summary of the 2017 edition of the trust survey, however, with a modest rise in trust levels in the 2019 edition. The US polling organisation Gallup, which also measures public approval of central institutions like banks, courts, congress, and the church, paints a similar picture. And, not least, the OECD finds that trust in government is also deteriorating in many OECD countries with only 42% of OECD citizens expressing trust in their national government — and with even lower trust in government among the youth.

One could argue that key societal institutions are suffering from a case of “trust inertia” in a world characterised by accelerating change and growing complexity. Yet there might be light at the end of the tunnel with the proliferation of new, advanced technologies that hold the potential to increase transparency and transform trust in ways that challenge the current, somewhat non-responsive, more centralised trust facilitating models.

One could argue that key societal institutions are suffering from a case of “trust inertia” in a world characterised by accelerating change and growing complexity.

Let’s take a look at a few examples. As large multinational banks fall under increased scrutiny, a growing number of brand-name financial institutions have become caught up in money laundering and tax evasion scandals. The size and scope of such scandals at the current moment only appears to be growing. Examples include the recent Russian money laundering scandal that has shattered confidence in Danske Bank, HSBC’s involvement in the billions laundered on behalf of Mexican drug cartels, and the exposure of how an international network of financiers, law firms, and big banks have systematically defrauded European tax authorities out of €55 bn.

But institutional trust breaches are by no means limited only to governments and financial institutions. The Panama Papers and Paradise Papers scandals have revealed tax evasion and the use of tax havens for a broad range of powerful multinational businesses as well as prominent individuals such as Nelson Mandela, Queen Elizabeth II of England, and football icon Lionel Messi. And it doesn’t stop there — what about Facebook and Cambridge Analytica’s data scandal or Volkswagen’s “Diesel-gate”? And we haven’t even discussed yet the term ‘fake news’, which permeates the media and presents a substantial threat to the idea of ‘truth’ and objectivity.

Modern society has largely arisen based on the development of trust in centralised systems and institutions. Historically, this has happened with the growing centralisation of state power and the associated development of judicial, monetary and other systems that made it possible to ‘outsource’ trust from individuals to institutions. Nations with strong and transparent institutions generally have higher levels of trust — while nations struggling with widespread corruption experience the opposite. In other words, trust is a pivotal part of the social contracts that we rely on as the foundation of our societies and our economic models. But, for a valid social contract to be upheld, citizens must fundamentally have trust in the institutions that keep society running.

While society’s fundamental institutions have obviously evolved a lot over time, they still function in essence as trusted middlemen. Today, established institutions and systems have an almost de facto monopoly on the facilitation of trust across most layers and levels of society. As a result, the public hasn’t been able to do anything but accept when, for example, Danske Bank pleads for forgiveness with promises of soul-searching, or when Mark Zuckerberg is reprimanded by the US Congress, but thereafter nothing really changes.

But the contours of a new trust paradigm are beginning to emerge. A paradigm in which trust is created and maintained in new ways and we no longer need to trust as much in opaque central authorities, global commercial monopolies, or other middlemen to manage our trust mechanisms. The combination of declining trust in established actors and systems, as well as the rise of emerging trust-enabling technologies, and a much more tech-savvy, vocal and activist younger generation is driving momentum toward a paradigm shift for trust.

The combination of declining trust in established actors and systems, as well as the rise of emerging trust-enabling technologies, and a much more tech-savvy, vocal and activist younger generation is driving momentum toward a paradigm shift for trust.

The latest technological development driving a potential revolution in trust-facilitation involves so-called distributed ledger technologies (DLTs), such as blockchain as the most well-known. DLTs offer the potential to circumvent reliance on traditional, centralised actors and institutions as the primary intermediaries for trust. Blockchain has been one of the most hyped technologies in recent years, and its most enthusiastic proponents claim that the technology has the potential to change the world to the same extent as the internet. Blockchain was developed as the underlying technological framework for Bitcoin and is therefore often equated with cryptocurrency speculation, despite this being a downright misconception. The technology’s potential to create trust spans well outside of the realm of financial transactions. However, at this time, most DLTs are still facing drawbacks such as scalability and energy usage before being able to fulfil their full potential.

There is no simple explanation for how DLTs works, but to put it briefly, a DLT system is a network of distributed digital ledgers in which every single participant in the network verifies and stores information through advanced encryption technology. In principle, the information stored on a DLT can be any data. It can be financial transactions between individuals, where one individual transfers money to another. But a transaction can also take the form of a notification that a container has just been loaded onto a ship, or personal health data that you can share with your doctor, to name just a few examples.

The most important conceptual advantage of DLTs is the “distributed” element. Today, the creation of trust in society is for the most part linked to centralised actors who have in many instances proved to be untrustworthy and opaque. In a DLT system, the creation of trust is shifted to the technology and a distributed network of users who ensure transparency and immutability. In theory this makes it possible to take the central actor such as the bank, the lawyer, or even Facebook, entirely out of the “trust equation”. The incentive for a break with centralised middlemen is also amplified by the fact that they are often expensive, burdensome, and now in many instances no longer inspire the required trust or confidence.

It is considerably more difficult to restore trust than it is to retain it. There is no short path to regaining trust once lost. And who knows, perhaps the trust in the established trust systems will suffer a deciding blow in the near future, concurrent with the rise of new trust alternatives and the continued “trust inertia” by established institutions.

It may be difficult to imagine how a new way of registering and storing information in a distributed digital ledger can bring about massive changes in social order. After all, the trust solutions of the future will not immediately topple society’s established trust facilitating institutions but will nonetheless force traditional institutions to overcome their ‘trust inertia” and re-invent themselves with the help of the very same trust-enabling technologies.

DLTs have the potential to either re-invent or undermine traditional trust facilitators, and established systems will undeniably be re-evaluated with the rise of viable trust alternatives that can offer a more secure, transparent, and in many instances cheaper and faster way of managing trust. It will, of course, take time before the new trust-enabling technologies will fulfil their full potential, with issues of scalability and energy usage still to be convincingly addressed. But this movement is underway.

This article was originally published in 2019 on the World Economic Forum agenda blog.