In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

The rise of Big Tech erodes national sovereignty in multiple ways and leads to a fragmented political landscape, requiring a reimagining of state power and new frameworks for unity.

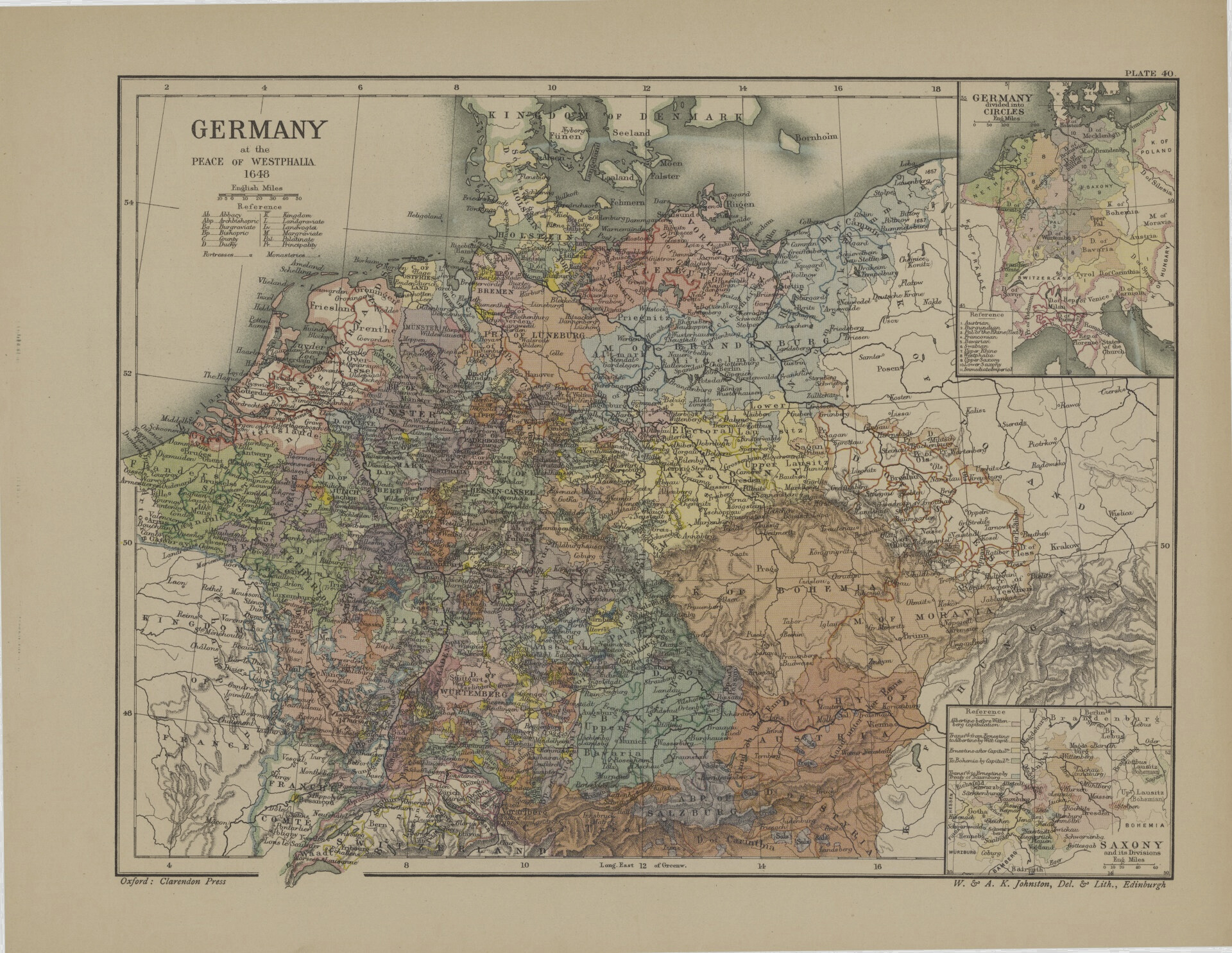

Photo: UConn Library Magic

As I write this, the 2024 Olympic games in Paris have just concluded. Earlier this summer, various regional football tournaments had many of us glued to our screens, wearing national jerseys, and singing along to our national anthems, whether we were football fans or not. In gloomier global news, numerous ongoing armed conflicts between neighbours are causing great tragedy to the civilian populations and a rift in the global order.

Very few things underline the boundaries of nation states as sports competitions and armed conflicts. Considering that the very idea of a nation, even more so a nation state, is mostly arbitrary and intangible, it can be hard to fathom how they can spur such emotion, gather such support, instil such a deep sense of belonging, ignite rivalry, and even war.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberAfter all, nations are human constructs. They are made up identities, divided by manmade borders that have ebbed and flowed over time. Many scholars, from Benedict Anderson in the 1980s to Yuval Harari today, have pointed out that nation states are part of the broader category of imagined realities which only exist in the collective imagination of large groups of people. Moreover, they have not always been around. We can trace their origins to the early modern period, particularly the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which established the principles of sovereign nation states. Ultimately, they are relatively recent, imagined, and perhaps temporary.

Many different factors have caused the rise and fall of states. Technological advancements take a prominent role on that list. The printing press, to take one example, is often pointed to as a pre-requisite for the emergence of nation states as the primary entity of political legitimacy. Print media, once it became widely available, helped give rise to vernacular languages – a key ingredient in fomenting nationalism. Surely, technology will continue to ignite prolonged and profound societal change.

In his recent book The Coming Wave, CEO of Microsoft AI Mustafa Suleyman asks how long our nation states and systems of governance can withstand the current leaps in technology before they will be shaken if not entirely dissolved. The coming decade in AI development, Suleyman writes, will cause a proliferation and democratisation of power for which we are not prepared. The challenge of our century, he contends, is not about unleashing technology’s power, as it was in the past, but to contain its unleashed power – to stay in control.

What might such an upset to the stability of nation states and the global order and institutions we have built on top of them look like?

For change in a system to occur there needs to be either pressure from within the system, stress to it from the outside, or both. The legitimacy of nation states and the world order that springs from them rests on a few simple promises: the state will provide security and services to meet the basic needs of its citizens. Security (defence) protects them from outside threats, such as armed conflicts, while the services will ensure (some) access to needs like education, healthcare, and vital infrastructure. Very simply put, successfully providing these amenities keeps people content and nations stable.

But in a time when security also encompasses cyber threats, when education, and to a great extent healthcare, can increasingly be offered and received virtually irrespective of proximity, and where ‘open and inclusive’ democracies are seeing a rise in populism, authoritarianism, and a backlash among their citizens in what is coined the ‘democratic recession’, this equation may start to lose its meaning.

What we are seeing is simultaneous centralisation and decentralisation of power because of tech. Decentralisation comes in the form of increased access and democratisation. Centralisation comes in the form the new tech providers’ unprecedented economic weight, global presence, and control of critical infrastructure. Suleyman compares the biggest contemporary tech providers to historical entities like the British East India Company, which wielded power greater than many nation states. From their relatively small headquarters in Britain, its reach and power stretched across the globe. Companies like Apple, Google, and Amazon are already bigger in economic terms than many countries. They control vast resources and data, their reach often surpassing that of national governments.

Imagine a day in your life in 2024: You wake up at 6:30 AM to a smartphone alarm and check your notifications, including those from a device which tracks your sleep. You put on the news while you get ready for work, log your breakfast in your dietary app, and secure your home via the security app before heading out. You then use your smartphone’s GPS to navigate to the train in time, pay for the ride through a mobile app, and spend the commute catching up on emails and work updates. At the office, you enter the building via a personalised key tag and log into your work computer.

Throughout the day, you use cloud-based tools and participate in video conferences. You work on projects using collaboration applications, which also track your activity and engagement levels. You grab coffee during your break using a loyalty app that tracks your purchase. You take an Uber home, with the app logging the trip and payment details. After a workout tracked by a smartwatch, dinner is prepared using a recipe app. You unwind watching Netflix, which logs your viewing preferences, and if you simultaneously interact on social media, that too is tracked and stored.

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereBy the time you turn off the lights, you will have produced a vast amount of data exhaust, reflecting your movement, health, dietary preferences, political views, your social network, work habits, hobbies and interests, your financial and spending habits, and more.

Not one government in the world has that kind of data access (although many would love to), but the tech providers do, and what’s more, a lot of the data will be centred with very few providers.

Such corporations challenge traditional state roles by their information access coupled with their control of critical infrastructure and services. Take, for instance, the pervasive influence of a company like Samsung in South Korea. A company that started as a noodle shop is now responsible for up to 20% of the entire national GDP and reaches into various sectors of life, mirroring the functions of a parallel government.

Of course, the entanglements of power and technology do not only serve to undermine state legitimacy, at least in the short term. These same technologies can serve to empower states, particularly authoritarian ones, such as in the case of AI-driven monitoring and facial recognition that enables unprecedented control over populations. China’s Sharp Eyes programme, aimed at surveilling public spaces comprehensively, is an example. In the long term, however, it remains to be seen whether the tools of control afforded to governments can withstand the technological tide that threatens to undermine their legitimacy more fundamentally.

This threat operates on a dual level. It not only concentrates power and undermines states’ monopoly on services, but also enables fragmentation, allowing small, tech-empowered groups to operate independently, potentially leading to a society where various entities form their own state-like structures.

This will inevitably challenge and potentially erode traditional notions of sovereignty as independent local ‘proto state’ structures grow, leading to a decay in the legitimacy and authority of nation states. Suleyman uses Hezbollah, or ‘Hezbollahization’, as an example of such an entity operating as a state within a state, as it runs its own schools, hospitals, infrastructure, and military operations independently of the official Lebanese government. Such developments are made possible elsewhere as well, with increasing democratisation and affordability of access to technology. One example which has come to the fore over the last decade is solar panel technology, which has seen a decrease in cost of more than 80 percent. Add increasing electrification and robotics, and we may eventually see energy self-sufficiency and manufacturing on a local scale. With the increased polarisation and tribalism witnessed across the world, we have a potent cocktail for alternatives to national governments.

So, as much as we may be used to nation states as the only legitimate governing entities, the notion that they might be dissolved in the future is supported by historical precedents, current trends in tech, the growth of corporate power – and, eventually, the local forms of organisation these tech providers empower. A scenario in which the functions and authority of nation states are significantly diminished, transformed, or replaced by new types of governance agents, aligns with the historical lessons we can draw from how technological innovations have impacted power structures in the past. It could eventually lead to a fragmented global political landscape. This may not necessarily be a bad thing, but it will take some getting used to and we will need new stories to tie us together – and perhaps new rules for the 2044 Olympics.

Get FARSIGHT in print!