In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Does the wisdom of the crowd combined with financial incentives produce the best forecasts of future events?

Photo: Ricardo Olvera

The papacy of Pius III was one of the shortest in history. Just a month after his appointment in September 1503, the new pope succumbed to a fever caused by an infected leg wound. Whispers circulated in Rome that he had been poisoned by a rival, yet the validity of such rumours was never confirmed.

The rule of Pius III is significant for other reasons than being exceptionally brief. It also marks history’s first documented instance of election betting. In Renaissance Italy, papal conclaves were the biggest show in town. Amid the frenzied public excitement they generated, fortunes were made and squandered speculating on who would be the next figurehead of the Catholic world.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberMoney is still made and lost in similar ways today. Papal elections may draw less attention than a US presidential race, but betting on future events is more popular and widespread than ever thanks to the recent growth of online prediction markets. On these markets, designed to reward the prescient and punish the uninformed, traders try their luck at profiting from their foresight.

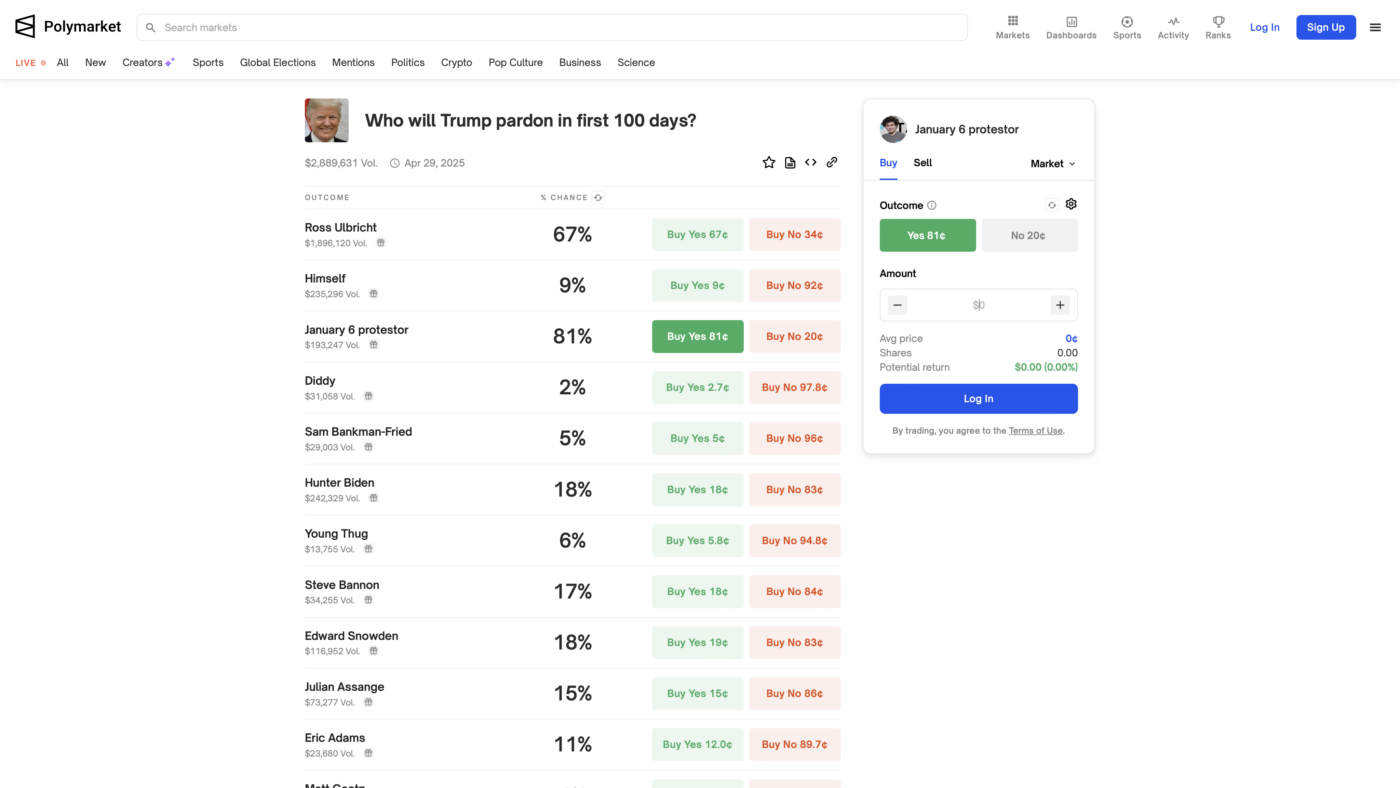

Prediction markets work in a similar way to more traditional financial markets. Buying a futures contract in expectation that the value of whatever you’re betting on will go up or down is, in a sense, also a forecasting exercise. But instead of betting on the future value of stocks, orange juice, or the yuan – which are impacted by unknown events – prediction markets allow you to bet on the outcome of events themselves. Bets are posed as questions, and you buy or sell shares either in the form of a ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Once the outcome is resolved, winning shares are paid out to the traders who chose correctly.

Polymarket dominates the field of prediction markets, outsizing all competitors in both volume and user count. The platform drew headlines during the 2024 US presidential election for how heavily its users bet on Donald Trump, pushing his odds to 67% to win when most election forecasts deemed the race a dead heat.

Not all the attention toward Polymarket was positive. In late October, the blockchain firms Chaos Labs and Inca Digital uncovered evidence that at least a third of the 2.7 billion USD in bets placed on the election was due to wash trading, creating a fake impression of market activity. Further complicating matters was Elon Musk, who touted Polymarket’s odds on X/Twitter as proof of an inevitable Republican landslide, drawing politically motivated participants and perhaps skewing the odds further. This is the Achilles heel of prediction markets: ulterior motives besides profit can distort the odds, resulting in misleading signals. Political betting, in other words, can become a political tool. This is especially an issue in markets with low liquidity, where a large bet can have a significant impact. As in traditional markets, insider trading also is a risk.

In the end, Polymarket was vindicated: it had been correct about the election’s outcome all along, even when most polls had been inconclusive about who would win, perhaps signalling a promising future for this hybridisation of gambling and forecasting. When the FBI raided Polymarket CEO Shayne Coplan’s apartment in November 2024, reportedly as part of a probe into whether his platform is run as an unlicensed commodities exchange, Coplan called the raid a retaliation for his success in “providing a market that correctly called the 2024 presidential election.”

Other markets have also gained momentum recently. In October 2024, a US federal appeals court permitted the trading platform Kalshi to list contracts that allowed Americans to bet on election outcomes. Following this ruling, other platforms have launched their own prediction markets.

Although the 2024 US election has accounted for most of the recent growth in these markets, it’s far from the only high stakes event attracting traders. Prediction markets offer event contracts for almost anything, from which way interest rates will go to where war will break out next. There’s always a wager on offer to lure users in with the prospect of growing their piles of crypto or cash.

Yet greed is not the entire story. Before Israel launched its attack on Iran in October 2024, Polymarket had been trading on the possibility. As the first airstrikes hit Tehran, the odds immediately spiked. News can break on prediction markets as quickly as in traditional media – sometimes even faster – while traders with real money at stake validate the news.

What some see as distasteful, others view as potentially filling a critical gap in our post-truth information landscape. Prediction markets are said to offer what many now don’t trust news outlets to provide: a reliable source of information. Because participants have a financial stake in the accuracy of their predictions, they’re incentivised to seek the most reliable information and discard misinformation, creating a system that reflects consensus on likely outcomes more accurately than individual opinions or standard news reporting.

Issues related to manipulation and herd behaviour aside, this supposed reliability is also what fuels the idea that prediction markets offer truer approximations of the probability of future events than other methods of prognosis. Since traders with information that the market may be missing will wager more confidently, the odds should be weighted toward the most likely outcome. Expertise is incentivised. Being wrong will cost you.

It sounds like a libertarian fever dream, but the idea that prediction markets can serve as effective forecasting tools does have some merit. When the Iowa Electronic Markets – the first experimental prediction market – launched in 1988, its founders were driven not by profit but by scientific inquiry.

That year, Jesse Jackson’s rapid ascent early in the Democratic primary election had stunned political pollsters. His performance towards the end of his run held even more surprises, as the progressive underdog went from overperforming to faltering unexpectedly.

Such upsets happen in politics, and there’s a whole slew of psychological ticks and survival mechanisms innate to us humans which can complicate the trustworthiness of polls. Will the stay-at-home mother vote as her domineering husband thinks? Does the outwardly progressive harbour a shy conservatism? In Jesse Jackson’s case, he may have had his initial momentum stunted by the so-called Bradley effect, where white American voters feel compelled to say they will vote for a minority candidate but won’t follow through on election day.

In a bar near Iowa University, a group of economics professors, just as confused as everyone else, were exchanging thoughts on how such polling blind spots could be mitigated. An idea arose to build a system that took advantage of the prognostic power of markets. In financial terms, Jesse Jackson’s stock had been wildly undervalued, then slightly overvalued, owing to incomplete data on voter psychology and behaviour. If a market had been available to weigh all existing information – including the Bradley effect – Jackson’s chances might have been more accurately reflected, and the twists and turns of his presidential primary run would have been less of a surprise.

That idea became the Iowa Electronic Markets, which opened to trading ahead of the presidential election of 1988. The platform came off to an impressive start by confidently and precisely predicting George H. W. Bush’s victory over Michael Dukakis when polls had been oscillating between the candidates. It was a watershed moment for prediction markets and has done much to bolster the idea that they are a strong method of prognosis.

How accurately these markets can forecast – and under what specific conditions – remains a matter of ongoing debate. Despite correctly predicting the 1988 election, the Iowa Markets hasn’t consistently outperformed poll-based forecasts. One 2008 study from the International Journal of Forecasting found that when compared to election polls in general, the Iowa Markets came closer to the eventual outcome 74% of the time when measured 100 days in advance of election day. Yet measurements on the eve of the election showed less conclusive evidence.

The Iowa Markets maintain credibility through transparency and strict limitations, capping bets at 500 USD per trader to avoid price manipulation by participants with deep pockets. But not all prediction markets are created equal. Polymarket, the far bigger platform by comparison, has fewer restrictions on users and no betting limits. The difference is the same as between a regulated financial market and a high stakes gambling den.

While sceptics argue that unrestricted prediction markets are susceptible to manipulation and hidden agendas, and that they therefore shouldn’t be trusted, proponents counter that in sufficiently large markets – such as a presidential race – manipulation would be prohibitively costly. Arbitrage opportunities between different markets would also serve to even out odds.

Not only that, but the most vocal proponents also believe we should put these markets to use in the name of good governance. Subsidise people’s innate desire to bet on what they believe will happen, the thinking goes, and in a sufficiently liquid market you could benefit from the unadulterated wisdom of the crowd, purified from bias by the prospect of converting insight into currency. That relative surety could then be harnessed to take more informed action.

The economics professor Robin Hanson has been making this argument for decades. He’s even proposed a system of governance, ‘futarchy’, in which betting markets are used deliberately to inform decision-making. In a futarchy, which Hanson envisions working for both governments and private companies, decisions are traded before being made, and proposals pass or fail depending on the judgement of the market.

Hanson’s instructive example is a scenario in which a company board must decide whether to let go of their CEO. The decision is sourced out to employees who are confronted with two scenarios – ‘sack’ or ‘keep’. In each scenario, the employees must assess whether the stock price would increase or decrease following the choice. If they decide that sacking their CEO would likely result in a higher stock price, then this decision is clearly correct.

The idea rests on the principle that to be effective, crowdsourced decision-making of any kind must include the participation of people with relevant information that might not otherwise come to the surface. In a company, those people may be holding back, not seeing a need (or perhaps feeling actively discouraged) from sticking their necks out and making their opinions known. An anonymous and incentivised prediction market might solve that issue.

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereSome companies already use internal prediction markets. Hewlett Packard, for instance, has tried to predict printer sales with them. Yet Hanson’s idea would take them from a forecasting tool to something that more directly informs high consequence decision-making on a wide, societal scale.

It’s no surprise that this idea resonates the strongest with rationalist, cryptoanarchist, and free market fundamentalist communities – mostly online. The crypto start-up MetaDAO is working on putting futarchy into practice, powered by a blockchain-based system. “Voting doesn’t work” they write on their website, because it’s not “a rational process where voters select the best option.”

It’s a curious interpretation of what voting is. Yet given the recent surge in prediction betting, other similar experiments with market-based decision-making may be on the horizon.

Enthusiasm is not restricted entirely to online thought bubbles either. Philip Tetlock, the political science professor who wrote Superforecasters and famously said that experts predict future events about as well as dart-throwing chimpanzees, supports the idea that prediction markets should be deregulated and experimented with for governance.

So far, most attempts have been quickly shut down. In 2001, the US Department of Defense began planning for an experimental prediction market, the Policy Analysis Market (PAM). The project, which would forecast geopolitical risks via futures contracts, was terminated already in 2003 amid heavy criticism and accusations that it was nothing more than a federal betting parlour for coups d’états, assassinations, and terrorist attacks. The Democratic senator Ron Wyden called the idea “ridiculous and grotesque.”

Robin Hanson, who acted as an advisor to PAM, thought the criticism was overblown and a misrepresentation of the project’s aims. In a Washington Post opinion piece, two other economists, Justin Wolfers and Eric Zitzewitz, defended PAM by presenting a hypothetical scenario: if a “Niger uranium sale” contract had existed before the US invasion of Iraq, it would have been nearly worthless, reflecting the prevailing intelligence that no such transaction had taken place. Perhaps it would have prevented the war, the economists insinuated. “Betting on human lives seems ethically questionable,” they wrote, “yet if it helps save lives, surely the moral questions are mitigated.”

Policy, of course, is not always a matter of having the right information. In the lead-up to the Iraq war, intelligence was selectively leveraged by US officials who knew much of it was contested or outright flawed, yet still pushed it forward to serve their aims. It’s doubtful whether a prediction market would have changed that. What’s certain is that these markets have now entered the public conversation, and general acceptance of them is closer today.

Their utility for high-consequence decision-making, however, remains a point of contention that depends on whether their flaws and vulnerabilities can somehow be designed away. If not, they will remain little more than glorified gambling platforms.

Get FARSIGHT in print.