In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

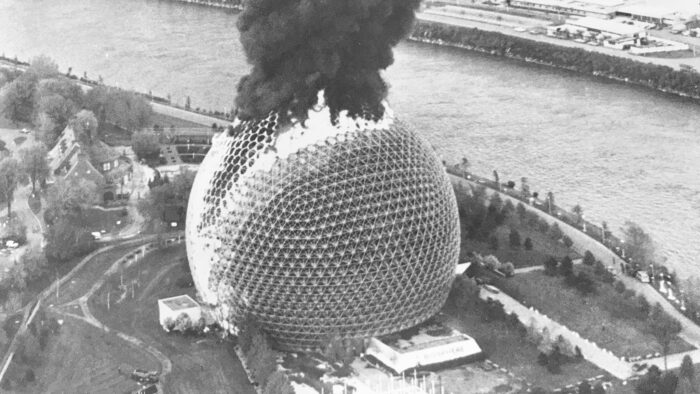

The Ethics of Ecological Sabotage

Can the ends justify the means?

Illustration: Sophia Prieto

In 1972, the Club of Rome commissioned The Limits to Growth, a pioneering study into the possibility of exponential economic growth on a planet with finite resources. The conclusion of the report was unambiguous: any increased exploitation of natural resources would be greatly unsustainable and necessitate direct limits on global consumption.

In the decades since, a wealth of research into our impact on the planet has been published, from the Club of Rome’s decennial follow-up studies to the regular IPCC reports on climate change produced since 1990. Today, anthropogenic climate change is acknowledged with a near universal consensus. The potential impact and severity of rising sea levels, increased frequency and severity of extreme weather phenomena, collapse of ecosystems, drought, forest dieback, and their collective after-effects are self-evident: widespread suffering and a total transformation of life as we know it.

It is tempting to envision an alternative series of events, perhaps one in which Al Gore won the historically close 2000 US presidential election and took global leadership on climate action. In reality, however, we experienced – and continue to experience – widespread inaction concerning climate change mitigation in nearly all countries. Despite desperate attempts by climate activists and scientists to nudge decision makers towards action with peaceful tools, progress remains much slower than what is necessary to be in accordance with the targets of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberThis relative passivity of political institutions has, in turn, led to an emergence of alternative methods of forcing policymakers to take necessary action. ‘Ecotage’ – sabotage carried out for ecological or environmental reasons – is one, ranging from the ‘Just Stop Oil’ activists throwing vegetable soup at Van Gogh paintings, to the sabotage of critical infrastructure, such as oil pipelines. The perpetrators of such acts believe that certain forms of strategic violence, particularly property damage, are justified to further the battle against climate change.

Given our current predicament, it seems likely that such violence will increase in the coming years.

Much of the intellectual foundation of ecotage is laid out in Andreas Malm’s 2021 book How to Blow up a Pipeline, in which the Swedish professor argues, as the title might suggest, that ecotage is a logical and necessary form of climate activism when considering the lack of success strategic nonviolence has had. While Malm strongly condemns the use of violence intended to hurt or kill people, he claims that it is necessary and perhaps even an obligation for climate activists to create a so-called ‘radical flank’ within the climate movement engaging in strategic ecotage. An example of this could be blowing up a pipeline during construction (preventing the risk of toxic spillage or loss of life incurred by an explosion after it was built). On a smaller scale, ecotage could take the form of flattening the tires of high-emission SUVs or other gas guzzlers.

Many believe it to be an obvious fact that strategic nonviolence is always the best way to achieve social change. In the best of all worlds, this would certainly be the case. Yet it may be an uncomfortable truth that history does not provide us with very compelling support for this notion.

In the 1980s, an American doctoral student by the name of Herbert H. Haines authored what has since become one of the most well-known studies of so-called ‘radical flank effects’. The paper examined the interactive processes between moderate and radical factions within social movements, where the actions of the radical flank were either beneficial or detrimental to the reputation and effectiveness of the moderate faction.

Haines found that militant Black activism in the US Civil Rights Movement led to funding increases for moderate mainstream civil rights groups and helped with the movement’s overall legislative success. Similarly, an analysis from the African National Congress argues that South African apartheid was defeated as a result of the combination of nonviolent and armed struggle. Furthermore, anti-apartheid activist Dali Tambo maintains that the nonviolence of Gandhi in India was only successful because the British knew that the next step would be mass violence on an uncontrollable scale.

It should be noted that a holistic view of the academic literature available paints a more unclear picture of the effectiveness of radical flanks, with some studies seemingly finding no significant results regarding their impact – and some coefficients even pointing towards their negative effects. Although examples like the above are convincing, the reality is that radical activism is so context-dependent and varies so greatly in degrees of militancy that no general assessment can be made about their overall effectiveness. Yet it’s clear that they can be very impactful under certain conditions.

For many, hearing the words ‘explosion’ and ‘oil pipeline’ in the same sentence might create associations of terrorism. Yet it would be worthwhile to consider whether the greater terrorist is someone who excessively harms the climate and environment, or someone who through illicit action seeks to prevent this harm. According to most (non-moralised) definitions, the former is typically portrayed as a ‘victim’ and the latter as an ‘eco-terrorist’. The ethical arguments on both sides are clear. On the one hand, one should not illegally destroy the property of other people. On the other hand, one should not stand idly by when severe damage is being done to ecosystems, the global climate, and in turn people all over the world, particularly those least advantaged. If we consider the harm done beyond the present moment – as is reasonable to do considering that atmospheric build-up of CO2 and ecological damage can take decades, if not centuries, to mitigate – we must naturally also consider the impact on future unborn generations.

One way of approaching the dilemma of property destruction is through the lens of what is known as ‘Just War Theory’ – a common doctrine that tries to reconcile our duty not to transgress the property rights of individuals with the need to defend justice, innocent lives, and the prevailing rights of citizens. ‘Property rights’ in this context can be understood as either attacks to individuals themselves – such as in war – or towards the private property such individuals own. Just War Theory simultaneously requires great moral justification from eco-saboteurs, while also legitimising their cause.

According to some revisionist positions, Just War Theory consists of two parts: the justification for going to war (jus ad bellum), and the justification for conduct in war (jus in bello). To meet jus ad bellum, three conditions must be achieved: the cause must be just, the expected positive effects must be proportional to those that are negative, and all nonviolent options must have failed. In turn, conduct in war also requires proportionality and necessity of each specific action, and targets must be liable for harm to be justified. Obviously, this cannot apply to objects, so in this context, the question of liability concerns the owners of the property.

In the case of climate change, the most relevant cause for war would likely fall under ‘humanitarian intervention’, as the aim of strategic ecotage is humanitarian by nature – with not only the intention of alleviating extensive future human suffering, but also defending the interests of a repressed group. Here, one group profits from emitting large amounts of greenhouse gases, while other groups, typically the least privileged and those without a voice, are the ones facing the bulk of the negative consequences. This leads to the final question of whether property destruction is proportional and, indeed, a last resort. Regarding proportionality, it depends on the expected effect of such ecotage, which admittedly is difficult to determine. However, since the violence is solely directed at inanimate objects rather than persons, the negative consequences are drastically lower than what is usual when using Just War Theory.

Combining these reflections with the fact that neither pleas from the scientific community nor mass-movements such as Greta Thunberg’s ‘Fridays for Future’ have had anywhere near the impact necessary for sufficient climate action, it appears plausible that the benefit of the doubt could perhaps justify strategic ecotage in such circumstances.

If the causes for strategic ecotage are accepted as proportional and necessary, then it follows that the actions of property damage, all other things being equal, would also be legitimate. However, this leaves the principle of discrimination remaining: whose property constitutes liable targets that can legitimately be destroyed? And, in turn, who determines this arbitrary degree of sufficient liability? These questions not only spring multiple moral philosophical dilemmas, but also raise a further question: can we really rule out that personal violence will be justified by the theory outlined above?

In the 2020 book The Ministry for the Future by science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson, widespread violence ensues after a great heat wave kills 25 million people in India. Following the catastrophe, eco-terrorists (or freedom fighters, depending on the eyes watching) attack those deemed most responsible for causing climate catastrophes and climate inaction such as oil lobbyists and airplane passengers – not unlike the activism of American domestic terrorist Theodore J. Kaszynski (otherwise known as ‘the Unabomber’). It is perhaps not far-fetched to expect an emergence of such incidents in real life as well.

Human beings are messy, however. Our actions tend not to be guided by abstract theories, but instead by the complex intuitions and irrationalities of the psyche. Even in the case of property-directed ecotage, determining arbitrary degrees of liability would not only need great moral justification, but also require a large part of the public to circumvent their belief in what is fair and just. These are questions that wrestle between utilitarian and duty-oriented (deontological) moral philosophies: either our moral guidance should follow from what produces the greatest expected utility, or it should be bound by a rule-based order prohibiting certain forms of behaviour – no matter how much welfare may be created as a result. As humans, we tend to be quite duty-oriented towards our fellow sapiens, and more utilitarian towards other species. This is, of course, a simplification, but the key takeaway still holds: personal violence is unlikely to be very prominent if strategic ecotage gains traction in public discourse. Practically, not only is it a huge mental barrier (for most) to harm other people, but it might also be difficult to assess liable targets (not to mention the risk of a lengthy jail time, which most people would go far to avoid).

Our threshold for what we consider acceptable means to an end tends to expand in times of extreme stress. Worsening climatic conditions, including increasingly destructive and deadly weather events, will likely play a greater role in forcing the issue of environmental activism than careful moral and ethical deliberations of exactly which actions are justifiable. Perhaps some 50 years from today, public attitudes will, as a result, have shifted to a more favourable view of ecotage. Or perhaps we will see a global division in attitudes, with populations in regions that are impacted the most but bear the least blame for past emissions becoming more prone to fostering and supporting radical action, while populations in wealthy, high-emission countries have the choice of taking the moral and ethical high road of condemning violence. What’s certain is that there is no hiding from the future, and the path we are on will force us to reckon with these difficult questions one way or another.

This is an article from

FARSIGHT: Safeguarding Tomorrow

Grab a copy here