In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

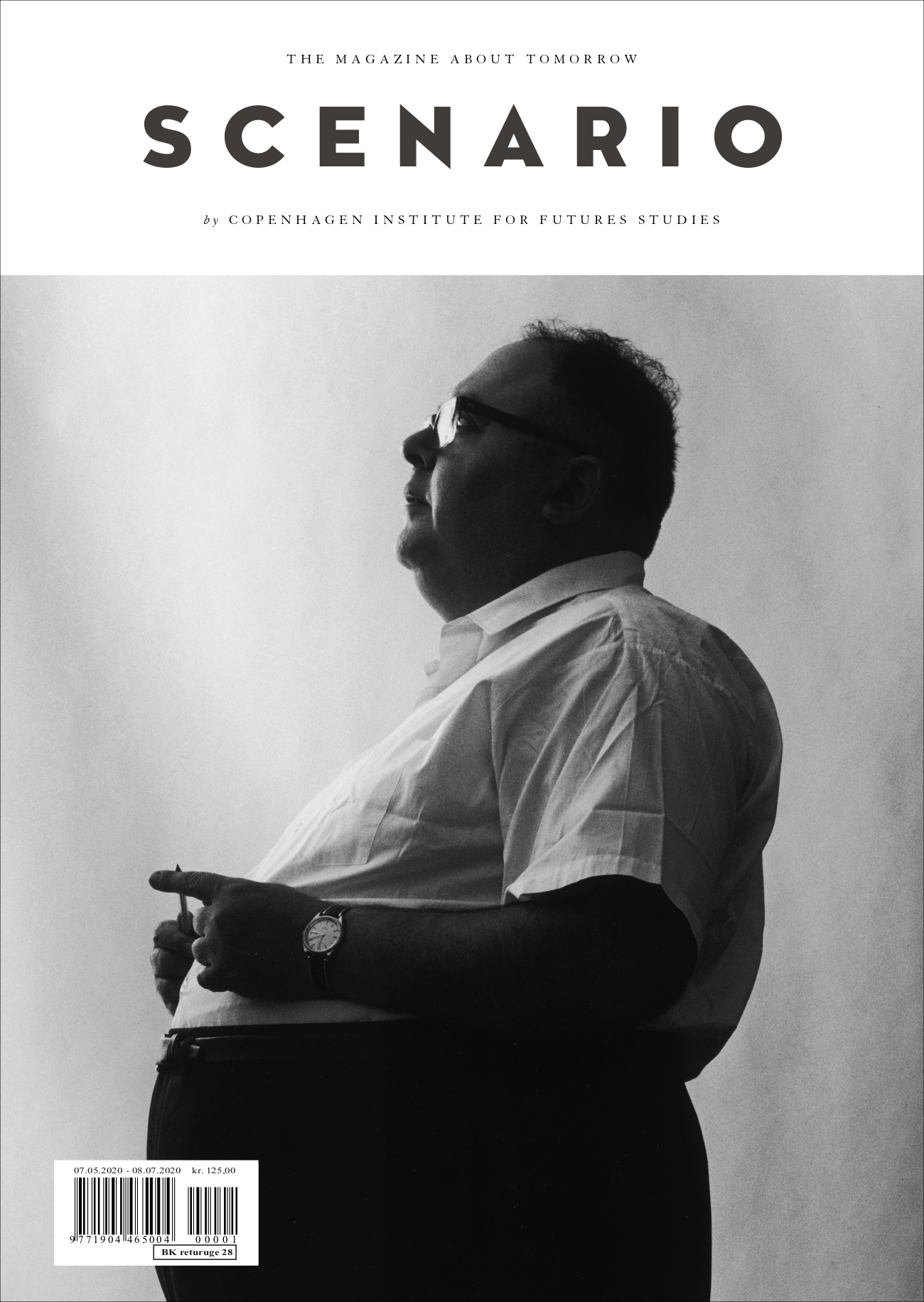

The Eccentric World of Herman Kahn

How one individual’s unconventionality (and controversy) helped shape Cold War strategy

and futures studies today.

(The article featured is part of the Institute’s Scenario Archives series)

In the early days of futures studies, the success of this sprawling but not yet established academic field depended on forceful ideas put forward by eccentric personalities. One of the greatest of them all was Herman Kahn. Few remember him today, but in the 1960s and 70s he was a household name – Herman Kahn was in his own words a one-man think tank. He was a mumbling fast-talker and a prolific writer known for giving twelve-hour marathon lectures. His theories contributed heavily to the development of the nuclear strategy of the United States during the Cold War, and he also helped to cement the status of futures studies as a practically applicable field that could be used in strategic planning by governments and organisations.

Like many big personalities of the past, Kahn is not easily pinned down. He was a futurist, meticulous analyst, scenario planner and military strategist, but he was also a wildly eccentric character whom one journalist at the time described as having “a thoroughly avant-garde sensibility”. Authors who have written biographies of Kahn are unsure whether to treat him as an intellectual or an artist due to his unconventional style of thinking and adventurous approach to anything he engaged in.

Kahn began his rise to fame and notoriety when he joined the RAND Corporation, the research arm of the US Air Force, in 1947. Although he made his career in planning military strategy and war games, he was not a soldier. The nuclear age called for theory over experience, since the kind of war that was anticipated had never been fought before. Nuclear preparedness was the realm of the mathematicians and theorists, not the generals. Kahn, with his willingness to think through the nasty and uncomfortable questions that the prospects of total war in the nuclear age called for, fitted the role perfectly. In 1961, he continued his quest to improve long-term preparedness when he founded the Hudson Institute – a think tank which became recognised and renowned for using scenario planning to forecast future trends and developments. It was during his time at the Hudson Institute that Kahn developed his most influential ideas and published his most widely read books.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

become a futures memberHerman Kahn had his fair share of critics. His detractors saw him as a cynical cold warrior, and a cursory reading of his most famous book, On Thermonuclear War, shows you why. The book, published a year before the Cold War almost turned hot during the Cuban Missile Crisis, was less concerned with how to prevent the mutually assured destruction of an atomic war fought between the United States and the Soviet Union, and more concerned with how such a war might progress – and what survival would look like in the aftermath. In the book, Kahn constructed a series of hypothetical war scenarios, which included assessments of casualties as well as descriptions of how ordinary people would live and rebuild civilisation in the wake of its destruction. The book contains some darkly fascinating passages that only the mind of Kahn could have thought of: In the event of a scenario that made food rationing necessary due to radiation, Kahn proposed a system for labelling food based on how contaminated it was, and feeding the contaminated food to the elderly (who would die before they got cancer anyway) so that the young could go on to live healthier and less irradiated lives. Kahn, who spent many of his waking hours calculating world-ending scenarios with astronomical death tolls, invented a new metric for this particular purpose: the megadeath (equalling one million human deaths). In all probability no one asked him to think these kinds of thoughts and put them on paper, but he did.

Kahn’s cynically realistic vision of post-nuclear futures was the reason he became one of the main sources of inspiration for Stanley Kubrick’s enthusiastically psychopathic Dr Strangelove, the ex-Nazi scientist who relishes the idea of an all-out nuclear exchange with the Russians. In one scene, in which a so-called “doomsday machine” is being discussed (a kind of global suicide device activated in the event of nuclear war), Dr Strangelove refers to a report by the BLAND Corporation – an obvious parody of RAND and a jab at the class of military planners and theorists of which Kahn was in the forefront.

Explore the world of tomorrow with handpicked articles by signing up to our monthly newsletter.

sign up hereEvidently, Stanley Kubrick was not a fan. However, other contemporaries had a different and more sympathetic understanding of Kahn and his worldview – even individuals far removed from the world of geopolitics and military planning. The psychologist and LSD guru Timothy Leary speculated that Kahn’s openness towards pondering the gruesome potentialities of the nuclear age was the result of him having participated in LSD sessions that expanded his mind and gave him the courage to be the proponent of unthinkable thoughts. As one reviewer remarked following the publication of On Thermonuclear War, Kahn set himself apart from his intellectual peers through his willingness to think beyond the so-called “strategy of deterrence”, which rested on the premise that nuclear war could be avoided if you had enough weapons in your arsenal to scare off your opponent. If we discount the influence of psychoactive drugs, perhaps Kahn’s willingness to engage with these undesirable but possible futures stemmed from his conviction that nuclear war, for all the tragedy that it would bring, would not necessarily prevent survivors from leading “happy” and “normal” lives in the aftermath.

Luckily for us all, none of the scenarios Kahn dedicated much of his life to thinking through ever materialised. While global nuclear war is obviously still a threat to civilisation, it is nowhere near the level of existential risk that it was in Herman Kahn’s time. As a result, many of his thoughts and ideas seem very much of their time and have little to offer us today.

That said, one central aspect of Herman Kahn’s legacy has maintained its relevance. He did not believe we could predict the future, but he certainly believed we could plan for it better, given the right tools. Futurists working today owe a great deal to his development of scenario planning as a viable and widely recognised method for anticipating alternative futures and planning strategies around them. More generally, Kahn dared us to think the unthinkable and to open our minds to all potentialities and timelines, including the ones that are almost too grim to contemplate.

This is an archive article from

Scenario Issue 56

Grab a copy here