In turn, we use cookies to measure and obtain statistical data about the navigation of the users. You can configure and accept the use of the cookies, and modify your consent options, at any time.

Will Workplace Privacy Become a Thing of the Past?

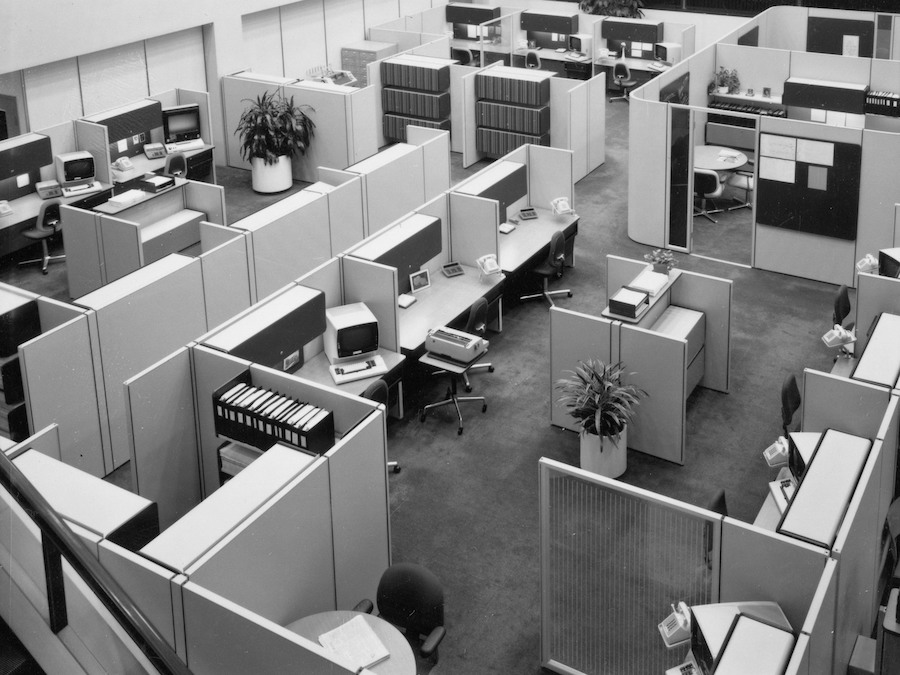

The collection and use of employee data is widely predicted to be a defining feature of future workplaces. Already, algorithmic management is central to the gig economy and is being adopted into industries such as banking and finance, healthcare, education, and retail. Although the collection and processing of workers’ data could mean improved efficiency and accuracy, reduced costs, as well as a greater capacity to remotely manage workforces, it comes at the expense of reduced employee privacy, agency and social protection.

So how much and what kind of data do we want our employer to have about us?

According to Aida Ponce Del Castillo, lawyer by training and senior researcher in the Foresight Unit for the European Trade Union Institute, we should proceed with caution, as she believes the risks related to the collection and use of sensitive employee data greatly outweigh any potential benefits. We spoke to Del Castillo to learn more about the rise of algorithmic management, and why she sees workplace data collection as a high-risk AI application for occupational health and safety.

How is algorithmic management currently integrated into the workplace?

Algorithmic management systems allocate tasks and allots how much time should be spent on them. These systems can measure how efficiently the task was completed in terms of time and performance, and if there should be a reward or a sanction. They can also determine the pay rate per task and provide recommendations on how to improve worker performance. Systems like these depend on the data extraction of the individual worker, gathering lots of personal and sensitive data to make detailed analysis and correlations. In doing this, we move from monitoring to surveillance of the employee.

These tools are a total game-changer to management as we know it. Yet they are far from neutral, as they do not simply allocate tasks, but also profile workers. They can predict worker performance and behaviours and even have the ability to ‘recognise’ their emotions.

“I believe that some uses of algorithms are useful, to some extent. But I also believe that some uses of algorithmic management should be totally banned.“

Why do you believe some aspects of algorithmic management should be banned?

In Europe, profiling workers using sensitive data – including data relating to facial expressions, emotions, and psychological indicators – is not allowed due to data protection laws (GDPR), except in very specific circumstances.

Yet we still see instances where this line is being crossed. During the Covid-19 pandemic, EU data protection authorities discovered many instances where employers were tracking and measuring all types of employee behaviour and activity (and inactivity), without workers knowing about it. This practice is unlawful, and the authorities asserted that employers must refrain from using these systems.

Broaden your horizons with a Futures Membership. Stay updated on key trends and developments through receiving quarterly issues of FARSIGHT, live Futures Seminars with futurists, training, and discounts on our courses.

BECOME A FUTURES MEMBERHere’s where you can see a real difference between worker monitoring and worker surveillance, which should not only be categorically distinguished in the common use of language, but also within our laws and legal systems. I think the law needs to go further than it currently does and clearly ban this in a workplace context.

Can algorithmic management effectively and ethically deliver safety in the workplace?

The principle that guides all occupational health and safety in the EU law is a principle of prevention. In terms of regulation, the employer is obliged to put organisational preventative measures in place to avoid employees being exposed to potential risks.

Prevention, in my opinion, is a human judgement. It involves rationality, common sense, and the application of rules, which is the law. However, prevention is very situational, because you never know how a human is going to act – we are creatures with freedom to do more or less whatever we want. We cannot simply prevent or foresee an employee falling, or an accident produced by external factors. This is why prevention policies need to take the uncertainty of environmental factors and human behaviours into account. Prevention cannot just be composed of metrics and features to be measured.

If we put a system in place to exert control, like a wearable notifying a worker that they are entering a dangerous environment, how a worker should do a task, or even simply telling the employee to ‘stand up because you’ve been sitting down too many hours’, then we are not really applying that principle of prevention. In fact, when we automate prevention, giving it metrics and benchmarks, this compromises a key principle in EU law – as it relies on very sensitive data of the worker.

“We cannot just trade privacy for safety, this is the wrong trade-off. And a very dangerous one.”

It is prohibited to process workers’ personal and sensitive data such as their health, psychological or emotional state. Occupational health and safety needs to pay attention to which systems are truly out of the boundaries of privacy and data protection.

As more and more companies are using algorithms based on personalised data to manage and control individuals not by force, but rather by nudging them into desirable behaviours, how might ‘algorithmic nudging’ affect occupational wellbeing?

The space for reflection and action becomes limited when we are nudged. How are we able to say no, to challenge the system? When employers put these systems in place, they are limiting the employee’s capacity to critically engage with their work and to activate their rights, and that can be damaging. This creates risks such as loss of autonomy, lack of transparency, bias, discrimination, or surveillance. And just because a technology is there it doesn’t mean that everyone will be able to use it accordingly. What about employees with limited literacy who are being nudged by a smartwatch given to them by their employer? The space for reflection becomes even more limited.

What the nudges also hide is the intentionality. If the worker received a buzz or an alert, you don’t necessarily have the capacity to understand why that system has given you the recommendation or command.

Do you think it is plausible that companies will want to gather personal data to improve the physical health and wellbeing of employees?

There are already large multinational companies making it clear they want to do this. One example of this is investments being made in early disease detection of employees by monitoring the cardiovascular system so heart attacks can be prevented. Obviously, this has real scope to benefit employee health, but I am also skeptical of the reason companies want to do this. The interest in monitoring employee health shouldn’t be accepted as being purely altruistic. Generally, companies are profit focused, so the basis for providing this kind of well-being needs to be taken with caution as it is an invasive practice that requires so much personal data collected.

What is one recommendation you would like to make that would protect workers?

Boundaries need to be in place at a very early stage of developing and using these management systems, so they do not harm very basic human and social rights. Human agency and foresight capacity needs to be upgraded to explore the long-term opportunities and possible impacts. How we want to shape technology and have it integrated into the workplace is an old question that requires continuous actions and answers.

Aida Ponce Del Castillo is a lawyer by training. She holds a Master’s degree in Bioethics and obtained her European Doctorate in Law, focusing on regulatory issues of human genetics, obtained at the University of Valencia. At the Foresight Unit of the European Trade Union Institute, her research focuses on the cross-boundary field between science and emerging technologies, ethical, social and legal issues. Additionally, she is in charge of conducting foresight projects. She has occupied various seats as an expert in specialised committees in EU institutions. At the OECD Aida is a member of the Working Party on Bio-, Nano- and Converging Technologies (BNCT) and on Al Governance.

CHECK-UP is a Q&A series by Maya Ellen Hertz and Sarah Frosh exploring advancements and providing critical reflections on innovations in digital health. From telemedicine and electronic health records to wearables and data privacy concerns, the article series includes interviews with experts in fields across law, engineering, and NGOs who shed light on the myriad of complexities that must be considered in the wake of new digital health technologies.